INTRODUCTION

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is considered as the most serious complication of cirrhosis and chronic liver disease. HCC is the sixth most common cancer, being the fourth leading cause of cancer mortality worldwide in 2018. It also accounts for the fifth most common cancer in males and the female's ninth most common cancer. Previous findings showed a 35% increase in the mortality rate (Bray et al., 2018; Dasgupta et al., 2020).

The therapeutic advancements over the past several years have brought about rapid evolvement to overcome HCC. Several approaches have been increasingly utilized to treat HCC, including hepatic resection, transplantation, radiofrequency ablation, chemoembolization, and systemic anticancer therapy (Grandhi et al., 2016; Ikeda et al., 2018).

Unfortunately, most HCC patients are diagnosed after the advanced stage since they do not show noticeable signs and symptoms early on (Bruix et al., 2016; Grandhi et al., 2016). In this scenario, multikinase inhibitors are the treatment of choice, with sorafenib (SOR) being the first-line treatment (Bouattour et al., 2019; Finn et al., 2018). Unfortunately, resistance to SOR develops rapidly about 6 months after treatment initiation (Bouattour et al., 2019; Cabral et al., 2020).

There are plenty of mechanisms that have been suggested regarding SOR resistance. Drug transporters were reported to be involved in the development of SOR resistance. Several studies described the involvement of ABC transporters and OCT1 uptake transporters affecting the efficacy of SOR (Edginton et al., 2016; Geier et al., 2017; Louisa and Wardhani, 2019; Tang et al., 2020; Tomonari et al., 2016).

Some studies have investigated the benefit of combination therapy to prevent or reduce SOR resistance. Alpha-mangostin (AM), a naturally occurring xanthone isolated from the pericarp of Garcinia mangostana, was previously studied in HCC cells. The results suggested that AM exerts its antitumor effect by inducing apoptosis and cell cycle arrest (Chang et al., 2013; Wudtiwai et al., 2018). Moreover, AM has shown modulatory activity in several multidrug-resistance transporters (Dechwongya et al., 2017; Laksmiani, 2019; Wu et al., 2017a).

In a recent study, Adenina et al. (2020) reported that the addition of AM to SOR in HCC cells' surviving SOR showed beneficial effect. However, the mechanism of how AM reduces cell viability in the previous system has not yet been elucidated. Consequently, the present study aimed to investigate the effect of AM in SOR-surviving HCC cells concerning several drug transporters' expressions.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells and cell culture

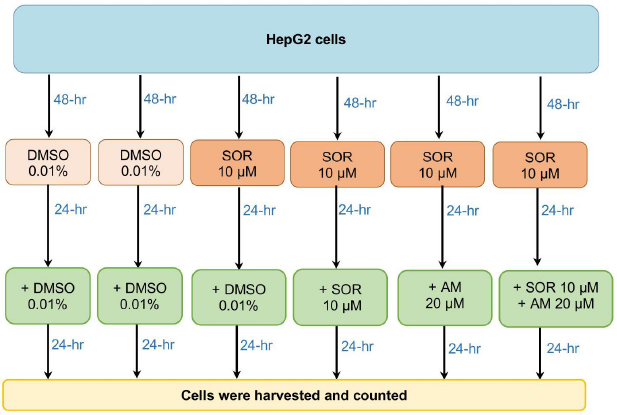

HCC cells, HepG2, were gifted by the Eijkman Institute for Molecular Biology. The cells were cultured as described previously (Louisa et al., 2016). Briefly, HepG2 cells were seeded in a culture dish for 48 hours until they reached the right confluence, divided into six treatment groups, as described in Figure 1. The first two groups that served as control were naïve HepG2 cells treated with vehicle only (DMSO) for 48 hours, followed by 24-hour treatment with DMSO or AM 20 mM. To select SOR-surviving cells, HepG2 was incubated with SOR 10 mM for 24 hours. Cells that survived 24-hour SOR 10 mM incubation were then considered SOR-surviving cells described by Adenina et al. (2020). Afterward, the medium was changed, and the cells were treated 24 hours with DMSO or SOR 10, AM 20 mM, or a combination of SOR 10 and AM 20 mM. Both AM and SOR were dissolved in DMSO at a final concentration of 0.01%. Then, the cells were counted using the trypan blue exclusion method and harvested.

Quantitative reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) of drug transporters

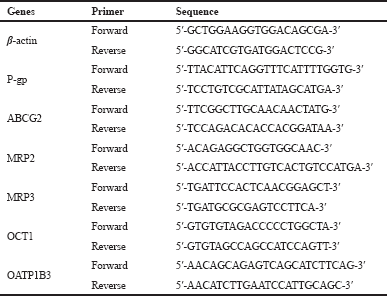

RNA was isolated from the harvested cells using Total RNA Mini Kit (Geneaid). RNA was then processed to cDNA using ReverTra Ace qPCR Master Mix with gDNA Remover (Toyobo). Analysis of P-glycoprotein (P-gp), ABCG2, MRP2, MRP3, OCT1, and OATP1B3 mRNA expressions was performed on qRT-PCR Light Cycler 480 (Roche) with Thunderbird SYBR qPCR Mix (Toyobo, Japan) using 100 ng of cDNA templates. The cycle threshold (Ct) was calculated automatically by using the software. The Ct data were then processed using the (Livak and Schmittgen, 2001) method to determine the normalized expression ratios of target genes. β-Actin was used as the housekeeping gene. Primers used in the present study were described in Table 1.

Data analysis

Results were presented in means ± SEM. Differences between groups were analyzed using the one-way analysis of variance test, followed by the post hoc Tukey method.

RESULTS

Cell viability

We observed a marked reduction in cell viability when SOR-surviving cells were treated with another dose of SOR or AM or SOR-AM combination, with the most potent effect being the combination group (Fig. 2). As for AM, treatment in naïve cells only resulted in a small cell viability reduction over control.

Drug efflux transporters

In HepG2 naïve cells, AM and SOR minimally affect the drug efflux transporters, while in SOR-surviving cells, treatment with SOR increased the mRNA expressions of BCRP, MRP2, and MRP3 but not P-gp. SOR tends to decrease the mRNA expressions of P-gp. The treatment of AM and SOR-AM combination significantly increased all of drug efflux transporters evaluated (P-gp, BCRP, MRP2, and MRP3) (Fig. 3).

| Figure 1. The flow of experiments in the study. [Click here to view] |

| Table 1. Primers used in the study. [Click here to view] |

| Figure 2. Percentage of cell viability over control after treatment of HepG2 cells with controls or HepG2 SOR-surviving cells treated with SOR or AM or combination of SOR-AM. Results are presented in mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05 versus DMSO-DMSO; #p < 0.05 versus DMSO-AM; &p < 0.05 versus Sor-DMSO. DMSO: DMSO 0.01%; AM = alpha-mangostin 20 mM; Sor = SOR 10 mM. [Click here to view] |

| Figure 3. The mRNA expressions of drug efflux transporters after treatment of HepG2 cells with controls or HepG2 SOR-surviving cells treated with SOR or AM or combination of SOR-AM. (A) P-gp; (B) BCRP; (C) MRP2; (D) MRP3. Results are presented in mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05 versus DMSO-DMSO; #p < 0.05 versus DMSO-AM; &p < 0.05 versus Sor-DMSO. DMSO: DMSO 0.01%; AM = alpha-mangostin 20 mM; SOR = sorafenib 10 mM. [Click here to view] |

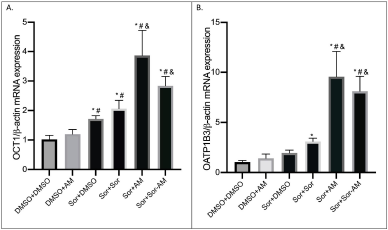

Drug influx transporters

Like drug efflux transporters, AM minimally affects drug influx transporters in HepG2 naïve cells, while SOR increased the expressions of OCT1 significantly. In SOR-surviving cells, all treatments (SOR, AM, and SOR-AM combination) increased OCT1 and OATP1B1 influx transporters, with AM treatment being the strongest. However, there were decreased expressions of OCT1 expressions in the SOR-AM combination when compared to AM alone.

DISCUSSION

The present study aimed to analyze the impact of AM on cell viability and its association with hepatic drug transporters mRNA expression in SOR-surviving human HCC HepG2 cell line.

Our study found that AM indeed modulated mRNA expression of six drug transporters that were examined in this study. This would then serve as an initial stepping stone, adding to a growing body of literature on AM's beneficial pharmacological properties.

Additionally, a recent study has demonstrated the chemosensitizing effect of AM, leading to its use as adjunctive treatment to the available anticancer chemotherapeutic agent. Adenina et al. (2020) also reported in their study regarding the reduced cell viability in SOR-surviving cancer cells following AM treatment. Nevertheless, the mechanism remained not fully understood. As for anticancer agents through drug transporters modulation, only a few studies have explored AM's impact on it (Chen and Duda, 2020; Ibrahim et al., 2016; Ovalle-Magallanes et al., 2017). The present study revealed that AM interestingly influenced drug transporters mRNA expression.

| Figure 4. The mRNA expressions of drug influx transporters after treatment of HepG2 cells with controls or HepG2 SOR-surviving cells treated with SOR or AM or combination of SOR-AM. (A) OCT1; (B) OATP1B3. Results are presented in mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05 versus DMSO-DMSO; #p < 0.05 versus DMSO-AM; &p < 0.05 versus Sor-DMSO. DMSO: DMSO 0.01%; AM = alpha-mangostin 20 mM; SOR = sorafenib 10 mM. [Click here to view] |

In terms of drug efflux transporters, it can be observed that the mRNA expression of the P-gp transporter showed a twofold decrease in SOR-surviving cells when treated with another dose of SOR. Our finding is in agreement with the study conducted by Beretta et al. (2017) and Tang et al. (2020) which reported the multitarget properties of SOR, including ABC transporters. From the mentioned study, it can be inferred that SOR has substrate-like properties at low concentrations while revealing its function of inhibition at higher concentrations such as the one used in the present study, that is, 10 μM. SOR concentrations used in this study were based on the highest achievable clinical blood concentration, as confirmed by Haga et al. (2017).

The other transporters on the same category in the present study, namely, ABCG2/BCRP, MRP2, and MRP3, in contrast to P-gp showed increased expression in SOR-surviving cells when treated with additional SOR dose. The possible underlying reason was that SOR displayed wide variability in affecting the drug transporters (Beretta et al., 2017). Thus, this cellular context that scientists are currently trying to elucidate could heavily impact the drug transporters with unpredictable outcomes (Beretta et al., 2017).

Regarding the impact of AM on efflux transporters, alone or in combination with SOR, it generally showed increased mRNA expression ranging from about 2- to 5-fold higher than SOR -surviving cells. Our results indicated that the condition of the “ SOR-surviving” cell line has already developed following initial administration of SOR 10 μM, as confirmed in a study by Haga et al. (2017) reporting its development of resistance with only 10.8% inhibition after 24-hour incubation. This may probably cause overexpression of the drug efflux transporters' mRNA that can no longer be suppressed by AM. The HepG2 cell line also showed the least inhibition amongst other cell lines used in that study, adding to the authors’ knowledge regarding the distinct intercell line variability of expression (Haga et al., 2017; Beretta et al., 2017). Another plausible explanation is that AM works more predominantly by inhibiting the function (instead of the mRNA expression) of the multidrug-resistance efflux transporters from producing the chemosensitizing effects as demonstrated in a study by Wu et al. (2017a), while another study reported a molecular docking analysis study using MCF-7 cells, which showed a relatively strong interaction between AM and P-gp as evidenced by the presence of three hydrogen bonds (Laksmiani, 2019).

Looking at the drug influx transporters that were examined in the current study, the mRNA expression of both OCT1 and OATP1B3 influx transporters showed a similar trend amongst all the treatment groups. Astonishingly, insight was gained concerning the increased expression in all treatment groups compared to SOR-surviving cells. This pointed toward the idea that the efflux transporters and the influx transporters also demonstrated increased mRNA expression significantly, ranging from 2.5-fold to almost 5-fold higher than the untreated one. While in SOR-AM combination group, the increase was not as high as if the cells were treated with AM only. The probable reasoning behind this is due to the possible interaction between the administered SOR 10 μM and AM 20 μM (Shukla et al., 2016). The SOR-surviving cells treated with the SOR group also showed the trend of higher mRNA expression compared to the untreated cells. The result was in line with a previous study that reported interference between SOR with OATPs and OCTs in addition to ABC transporters (Shukla et al., 2016).

A meta-analysis by Burt et al. (2016) had managed to reveal the quantitative abundance of hepatic transporters in the Caucasian population. HepG2 cell lines were initially derived from a well-differentiated liver tumor of a 15-year-old Caucasian male (Dubbelboer et al., 2019). Several interpretations can be made using meta-analysis data about the proportions of liver drug transporters. The protein abundance proportion of OATP1B3 and OCT1 is 31% and 12%, respectively (Shukla et al., 2016). The ratio of MRP2, P-gp, MRP3, and ABCG2 from that meta-analysis showed merely 2%, 2%, 1%, and 0.34%, respectively. The remaining ~51.66% proportion of transporters from the meta-analysis were not studied in the present study. Nevertheless, the trend still revealed more predominant influx transporters (~44%) compared to efflux transporters (~7.66%) (Shukla et al., 2016).

Recapitulating the number of folds of increased mRNA expression of AM treatment in SOR-surviving cells from the present study, the highest for efflux and influx transporters were MRP3 and OATP1B3 with 5.6-fold higher and 4.9-fold higher, respectively. At this point, it seemed that MRP3 showed more increase, which gave the impression of net efflux effect following the AM treatment. However, we could, fortunately, appreciate from the previous paragraph that OATP1B3 serves as the most abundant transporter (31%), while MRP3 is only 1% of the total abundance. To put it another way, although efflux transporters have a higher number of folds compared to the influx, it has a much smaller proportion compared to influx transporters, which are more superior in terms of the quantitative abundance. At this moment, the net influx effect would then be the predominant one to be observed. This calculation again obviously needed closer inspection since the meta-analysis was revealing data of protein abundance, while the present study was showing results of mRNA expression. However, Liu et al. (2016) suggested that despite the substantial contribution of posttranscriptional regulation that may occur, it may only minimally alter the abundance rank of the protein in a cell. Therefore, the posttranscriptional impact did not seem to markedly affect the relative differences between proteins, which consequently supported the author's analysis of the present study (Liu et al., 2016). Aside from abundance, Beretta et al. (2017) research also suggested SOR inhibiting properties on many efflux transporters.

As for AM, it was confirmed by some studies to enhance the anticancer effect (Wu et al., 2017a, 2017b; Wudtiwai et al., 2018) which leads to the AM potential of exerting chemosensitizing effects by modulating drug transporter's expression. The findings in this study managed to provide a fair investigation by revisiting the roles of efflux transporters and appreciating the influx transporters in terms of their role in anticancer resistance.

In conclusion, our study confirms that AM did influence the mRNA expression of both efflux and influx drug transporters in a SOR-surviving HCC cell line (HepG2).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors acknowledge the Indonesian Ministry of Research and Technology, National Research and Innovation Agency, for providing the Basic Research and Higher Education Excellence Grant 2020.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

All authors made substantial contributions to conception and design, acquisition of data, or analysis and interpretation of data; took part in drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content; agreed to submit to the current journal; gave final approval of the version to be published; and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work. All the authors are eligible to be an author as per the international committee of medical journal editors (ICMJE) requirements/guidelines.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors report no financial or any other conflicts of interest in this work.

ETHICAL APPROVALS

Not applicable.

PUBLISHER’S NOTE

This journal remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published institutional affiliation.

REFERENCES

Adenina S, Louisa M, Soetikno V, Arozal W, Wanandi SI. The effect of alpha mangostin on epithelial-mesenchymal transition on human hepatocellular carcinoma HepG2 cells surviving sorafenib via TGF-β/Smad pathways. Adv Pharm Bull, 2020; 10(4):648–55. CrossRef

Beretta GL, Cassinelli G, Pennati M, Zuco V, Gatti L. Overcoming ABC transporter-mediated multidrug resistance: the dual role of tyrosine kinase inhibitors as multitargeting agents. Eur J Med Chem, 2017; 142:271–89. CrossRef

Bouattour M, Mehta N, He AR, Cohen EI, Nault JC. Systemic treatment for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. Liver Cancer, 2019; 8(5):341–58. CrossRef

Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin, 2018; 68(6):394–424. CrossRef

Bruix J, Reig M, Sherman M. Evidence-based diagnosis, staging, and treatment of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastroenterology, 2016; 150(4):835–53. CrossRef

Burt HJ, Riedmaier AE, Harwood MD, Crewe HK, Gill KL, Neuhoff S. Abundance of hepatic transporters in caucasians: a meta-analysis. Drug Metab Dispos, 2016; 44(10):1550–61. CrossRef

Cabral LKD, Tiribelli C, Sukowati CHC. Sorafenib resistance in hepatocellular carcinoma: the relevance of genetic heterogeneity. Cancers (Basel), 2020; 12(6):1576. CrossRef

Chang HF, Wu CH, Yang LL. Antitumour and free radical scavenging effects of γ-mangostin isolated from Garcinia mangostana pericarps against hepatocellular carcinoma cell. J Pharm Pharmacol, 2013; 65(9):1419–28. CrossRef

Chen J, Duda DG. Overcoming sorafenib treatment-resistance in hepatocellular carcinoma: a future perspective at a time of rapidly changing treatment paradigms. EBioMedicine. 2020; 52:102644. CrossRef

Dasgupta P, Henshaw C, Youlden DR, Clark PJ, Aitken JF, Baade PD. Global trends in incidence rates of primary adult liver cancers: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Oncol, 2020; 10:171. CrossRef

Dechwongya P, Kulsirirat T, Dheeraprempree B, Boonnak N, Satirakul K. High-throughtput screening the interaction of xanthones from mangosteen pericarps with P-glycoprotein transporter. Drug Metab Pharmacokinet, 2017; 1(32):S100. CrossRef

Dubbelboer IR, Pavlovic N, Heindryckx F, Sjögren E, Lennernäs H. Liver cancer cell lines treated with doxorubicin under normoxia and hypoxia: cell viability and oncologic protein profile. Cancers (Basel), 2019; 11(7):1024. CrossRef

Edginton AN, Zimmerman EI, Vasilyeva A, Baker SD, Panetta JC. Sorafenib metabolism, transport, and enterohepatic recycling: physiologically based modeling and simulation in mice. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol, 2016; 77(5):1039–52. CrossRef

Finn RS, Zhu AX, Farah W, Almasri J, Zaiem F, Prokop LJ, Murad MH, Mohammed K. Therapies for advanced stage hepatocellular carcinoma with macrovascular invasion or metastatic disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hepatology, 2018; 67(1):422–35. CrossRef

Geier A, Macias RI, Bettinger D, Weiss J, Bantel H, Jahn D, Al-Abdulla R, Marin JJG. The lack of the organic cation transporter OCT1 at the plasma membrane of tumor cells precludes a positive response to sorafenib in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncotarget, 2017; 8(9):15846. CrossRef

Grandhi MS, Kim AK, Ronnekleiv-Kelly SM, Kamel IR, Ghasebeh MA, Pawlik TM. Hepatocellular carcinoma: from diagnosis to treatment. Surg Oncol, 2016; 25(2):74–85. CrossRef

Haga Y, Kanda T, Nakamura M, Nakamoto S, Sasaki R, Takahashi K, Wu S, Yokosuka O. Overexpression of c-Jun contributes to sorafenib resistance in human hepatoma cell lines. PloS One, 2017; 12(3):e0174153. CrossRef

Ibrahim MY, Hashim NM, Mariod AA, Mohan S, Abdulla MA, Abdelwahab SI, Arbab IA. α-Mangostin from Garcinia mangostana Linn: an updated review of its pharmacological properties. Arab J Chem, 2016; 9(3):317–29. CrossRef

Ikeda M, Morizane C, Ueno M, Okusaka T, Ishii H, Furuse J. Chemotherapy for hepatocellular carcinoma: current status and future perspectives. Jpn J Clin Oncol, 2018; 48(2):103–14. CrossRef

Laksmiani NPL. Ethanolic extract of mangosteen (Garcinia mangostana) pericarp as sensitivity enhancer of doxorubicin on MCF-7 cells by inhibiting P-glycoprotein. Nusantara Biosci, 2019; 11(1):49–55. CrossRef

Liu Y, Beyer A, Aebersold R. On the dependency of cellular protein levels on mRNA abundance. Cell, 2016; 165(3):535–50. CrossRef

Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods, 2001; 25(4):402–8. CrossRef

Louisa M, Suyatna FD, Wanandi SI, Asih PBS, Syafruddin D. Differential expression of several drug transporter genes in HepG2 and Huh-7 cell lines. Adv Biomed Res, 2016; 5:104. CrossRef

Louisa M, Wardhani BW. Quercetin improves the efficacy of sorafenib in triple negative breast cancer cells through the modulation of drug efflux transporters expressions. Int J Appl Pharm, 2019; 11(Special Issue 6):129–34. CrossRef

Ovalle-Magallanes B, Eugenio-Perez D, Pedraza-Chaverri J. Medicinal properties of mangosteen (Garcinia mangostana L.): a comprehensive update. Food Chem Toxicol, 2017; 109(Pt 1):102–22. CrossRef

Shukla S, Patel A, Ambudkar SV. Mechanistic and pharmacological insights into modulation of ABC drug transporters by Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors. In: AM George (ed.). ABC transporters - 40 years on, Springer International Publishing, Cham, Switzerland, pp 227–72, 2016. CrossRef

Tang W, Chen Z, Zhang W, Cheng Y, Zhang B, Wu F, Wang Q, Wang S, Rong D, Reiter FP, De Toni EN, Wang X. The mechanisms of sorafenib resistance in hepatocellular carcinoma: theoretical basis and therapeutic aspects. Signal Transduct Target Ther, 2020; 5(1):87. CrossRef

Tomonari T, Takeishi S, Taniguchi T, Tanaka T, Tanaka H, Fujimoto S, Kimura T, Okamoto K, Miyamoto H, Muguruma N, Takayama T. MRP3 as a novel resistance factor for sorafenib in hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncotarget, 2016; 7(6):7207. CrossRef

Wu CP, Hsiao SH, Murakami M, Lu YJ, Li YQ, Huang YH, Hung TH, Ambudkar SV, Wu YS. Alpha-mangostin reverses multidrug resistance by attenuating the function of the multidrug resistance-linked ABCG2 transporter. Mol Pharm, 2017a; 14(8):2805–14. CrossRef

Wu JJ, Ma T, Wang ZM, Xu WJ, Yang XL, Luo JG, Kong LY, Wang XB. Polycyclic xanthones via pH-switched biotransformation of α-mangostin catalysed by horseradish peroxidase exhibited cytotoxicity against hepatoblastoma cells in vitro. J Funct Foods, 2017b: 28:205–14. CrossRef

Wudtiwai B, Pitchakarn P, Banjerdpongchai R. Alpha-mangostin, an active compound in Garcinia mangostana, abrogates anoikis-resistance in human hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Toxicol In Vitro, 2018; 53:222–32. CrossRef