INTRODUCTION

SARS-CoV-2 is causing a global pandemic of the respiratory disease coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), with multiple acute and long-term complications (Chen et al., 2020). Since the COVID-19 pandemic outbreak from Wuhan, China, scientists have been looking for effective vaccines or novel antiviral agents for the SARS-CoV-2 virus (Kandeil et al., 2021; Mahmoud et al., 2020). Scientists were attracted to a variety of natural products of different sources and organisms that can provide new opportunities for the treatment and prevention of infectious diseases (Khare et al., 2020). More than 70% of living organisms are represented by insects (Loram, 2006). Insects have long been used as food, medication, and chemical products due to their abundance and variety in the human environment. For more than 2,000 years, medicinal insects and their products have been used as part of Chinese medicine to treat ailments, whether directly or indirectly, and insect-related drugs may be derived from adult insects or larvae (Feng et al., 2009). Maggots (fly larvae), especially Lucilia sericata and Lucilia cuprina maggots, were used in wound treatments (Hassan et al., 2014; Sherman, 2009). The maggots produce excretion/secretion (E/S) containing serine proteases and antioxidants (such as cysteine and glutathione), among other active ingredients (Casu et al., 1994; Chambers et al., 2003; Gupta, 2008; Nigam et al., 2006; Vistnes et al., 1981). E/S has effects against bacteria (Jiang et al., 2012; Van der Plas et al., 2008), fungi (Pöppel et al., 2014), and viruses (Abdel-Samad, 2019).

The viral entry of SARS-CoV-2 was shown to be through binding of its spike protein (S-protein) with angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) receptors on the cell membrane facilitated by the transmembrane protease, serine 2 (TMPRSS2). TMPRSS was shown to proteolytically cleave and activate the SARS-CoV-2 S-protein, among many other viruses, promoting viral uptake (Ragia and Manolopoulos, 2020). Another pathway of viral entry utilizes cathepsin B (endosomal pathway), which is a cysteine protease expressed in endosomes and acts by facilitating the fusion of the viral and endosomal membrane. Cathepsin B works independently from TMPRSS2 (Padmanabhan et al., 2020). Targeting TMPRSS2 and/or cathepsin could hinder viral entry and decrease viral load.

The viral infection was shown to dysregulate multiple pathways related to immunity, protein degradation, blood coagulation, neuronal functions, among many others. One of the important pathways involved in immunity is the Notch signaling pathway which affects the differentiation of the lymphoid T and B cell lineages. The Notch pathway was proved to be involved in several bacterial and viral infections via multiple mechanisms affecting inflammation and several cell signaling pathways (Ito et al., 2011; Keewan and Naser, 2020; Lu et al., 2020), including the pathogenesis of SARS-CoV-2 (Breikaa and Lilly, 2021).

Protein degradation pathways such as ubiquitination, SUMOylation, and Neddylation were reported to be dysregulated in viral infections (Masucci, 2020). In SARS-CoV-2 infection, the SUMOylation and Neddylation pathways were previously shown to be dysregulated (Ibrahim and Ellakwa, 2021). SUMO could be a potential target in the treatment of SARS-CoV-2 infection (Ryu, 2021).

One of the important defence defense mechanisms of host cells against viral infection is enzymatic deamination of viral DNA by host cells. The base excision repair gene TDG glycosylases was were reported to be dysregulated in viral infection (Pytel et al., 2008). TDG is known to affect immunity, particularly innate immunity (Jacobs and Schär, 2012). It is also known to be involved in SUMO signalling signaling (Smet-Nocca et al., 2011).

Inhibition of the TMPRSS2 and cathepsin pathways was shown to be effective against coronaviruses infection (Kawase et al., 2012) and in SARS-CoV-2 infection (Ragia and Manolopoulos, 2020). This study aims to assess the potential efficacy of L. cuprina maggots’ E/S in preventing cell entry of SARS-CoV-2 infection and progression of COVID-19 for the first time. It also aims to assess its effect on key genes and pathways related to SARS-CoV-2 pathogenesis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

E/S collection

Lucilia cuprina maggots’ E/S was obtained using procedures described in the literature (Abdel-Samad, 2019). In brief, L. cuprina maggots in their third larval instar were isolated from a maintained laboratory culture of L. cuprina at the Animal House, Faculty of Science, Al-Azhar University. The isolated maggots were washed with 70% ethyl alcohol followed by distilled water, before being incubated in darkness with phosphate-buffered saline for 6 hours at 25°C. The E/S was collected, centrifuged, filtrated, and stored at −20°C.

In vitro antiviral activity

Cells and virus

In a humidified incubator at 37°C and 5% CO2, the VERO-E6 cells (ATCC® CRL-1586™) were sustained in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (DMEM) containing 1% penicillin/streptomycin and 10% fetal bovine serum. The SARS-CoV-2 “NRC-03-nhCoV” virus (Kandeil et al., 2020) was propagated and titrated as previously described (Mostafa et al., 2020).

Cytotoxicity determination

Half-maximal cytotoxic concentration (CC50) of L. cuprina was assessed in VERO-E6 cells using the crystal violet assay as previously described (Feoktistova et al., 2016). Briefly, L. cuprina maggots’ E/S stock solutions were prepared in 10% Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) in ddH2O; several dilutions of this solution were prepared using DMEM. In parallel, the cells were seeded in 96-well plates (100 µl/well, density of 3 × 105 cells/ml) and incubated for 24 hours in a 5% CO2 humidified incubator at 37°C. After the incubation period, cells were treated with various concentrations of the E/S in triplicate. After 72 hours, the supernatant was discarded, and cell monolayers were fixed using 10% formaldehyde for 1 hour at room temperature (RT). The fixed monolayers were then dried and stained with 50 µl of 0.1% crystal violet for 20 minutes on a bench rocker at RT. The stained cell monolayers were washed and dried, and then the crystal violet dye was dissolved with methanol (200 µl/well for 20 minutes) on a bench rocker at RT. The absorbance of crystal violet solutions was measured at λmax 570 nm using a multiwell plate reader. The CC50 of the E/S is the concentration required to induce the L. cuprina E/S-related cytotoxicity by 50%, relative to the virus control.

Inhibitory concentration determination

The half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) value for L. cuprina E/S was determined as previously described (Mostafa et al., 2020), with minor modifications. Briefly, VERO-E6 cells were seeded in 96-well tissue culture plates (2.4 × 104/well) and incubated overnight in a 5% CO2 humidified incubator at 37°C. The cell monolayers were then washed using 1 × phosphate buffer saline (PBS). An aliquot of the SARS-CoV-2 virus containing 100 TCID50 was incubated with serial dilutions of L. cuprina E/S and kept at 37°C for 1 hour. The VERO-E6 cells were treated with the virus alone or virus/L. cuprina E/S mixture and incubated at 37°C in a total volume of 200 µl per well. Cell control was cells that were not treated and not infected, and untreated cells infected with virus represented virus control. After incubation in a 5% CO2 incubator for 72 hours at 37°C, cells were fixed using 10% paraformaldehyde for 20 minutes and stained using 0.5% crystal violet in dH2O for 15 minutes at RT. Crystal violet was then dissolved using absolute methanol (100 μl/well), and the absorbance of crystal violet solutions was measured at λmax 570 nm using a multiwell plate reader. The IC50 of the compound is the concentration required to reduce the virus-induced cytopathic effect by 50%, relative to the virus control.

Plaque infectivity assay

To determine the impact of E/S on monocycle (12 hours after infection) and multicycle replication (24–36 hours after infection) kinetics of SARS-CoV-2, confluent monolayers of VERO-E6 cells were infected in triplicate with the virus at a multiplicity of infection of 0.1 in a humidified CO2 incubator at 37°C. After 1 hour of virus-cell incubation at RT, the inoculum was discarded and cell monolayers were washed twice with PBS++ (PBS containing 100 mg/l CaCl2 and 100 mg/l MgCl2) and replaced with infection medium DMEM/BA [DMEM, supplemented with 0.2% BA, 1% P/S, and 1 μg/ml L-1-tosylamido-2-phenylethyl chloromethyl ketone (TPCK)-treated trypsin] containing 5 µg/ml (n = 3) or without (n = 3) E/S. Supernatants were collected at 12, 24, and 36 hours after infection (p.i.) and stored at −80°C. For the titration of the viral load in the stored samples, a plaque infectivity assay was carried out as previously described (Mostafa et al., 2020; Payne, 2017)

Protein–protein interaction (PPI) prediction

The Prediction Server of Protein-protein InterActions (PSOPIA) prediction tool (Murakami and Mizuguchi, 2014) was used to predict the interaction between L. cuprina E/S serine protease and SARS-CoV-2 S-protein, ACE2, TMPRSS2, cathepsin B, or cathepsin L. For the study genes, STRING (Szklarczyk et al., 2019) was used to evaluate the PPI enrichment and to find the protein network of the study genes. p value < 0.05 and false discovery rate (FDR) <0.05 were considered to be significant.

Gene expression assay

RNA extraction

VERO-E6 cells were infected with 500 TCID50 of SARS-CoV-2. At time intervals of 6, 12, and 24 hours after infection, cells were collected in 1 × PBS, pelleted by centrifugation, and RNA was extracted using the RNeasy Mini Kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The extracted RNA was treated with 2 µl (100 U) DNase I (Invitrogen) C for 1 hour at 37°C and cleaned up using 3M sodium acetate and absolute ethanol as described previously (Petersen et al., 2018). The mRNA expression of selected genes following infection with SARS-CoV-2, with and without treatment with L. cuprina E/S, was assessed via Quantitative Reverse Transcription polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR).

qPCR

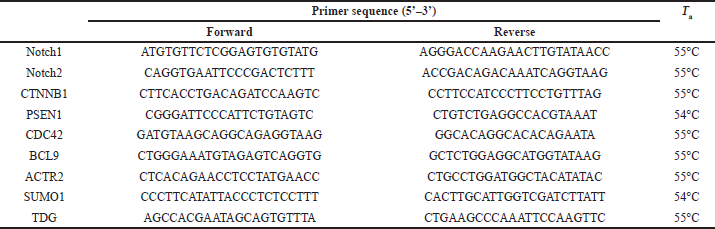

Total RNAs were extracted from treated and untreated cells using the QIAamp RNA Blood Mini Kit (QIAGEN) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The extracted mRNA was reverse-transcribed into cDNA using the RevertAid First Strand cDNA CDNA Synthesis Kit (Thermo Scientific). For qRT-PCR of Notch1, Notch2, CTNNB1, PSEN1, CDC42, BCL9, ACTR2, SUMO1, and TDG, primers were designed using the Primer3 software (https://primer3.ut.ee/,RRID:SCR_003139). Amplification mixtures were prepared using Maxima SYBR Green qPCR Master Mix (Thermo Scientific, USA). Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) was used as an internal reference gene to normalize the expression. Samples were prepared in technical replicates at three time points (6, 12, and 24 hours after infection). Results were expressed as a ratio of reference to target gene using the 2−ΔΔCt method (delta-delta Ct method or qPCR is a simple formula used to calculate the relative fold gene expression of samples when performing real-time polymerase chain reaction), and fold changes were normalized. Primers and annealing temperature Ta for each are listed in Table 1. qPCR cycling conditions were 95°C for 10 minutes [95°C for 15 seconds, Ta (as listed below in Table 1) for 30 seconds, and 72°C for 40 seconds] (40 cycles).

Statistical analysis

All experiments were performed in triplicate, and the data are presented as the average of the means. The significant differences (p ≤ 0.05) between the values of the control and treatment groups were determined using two-tailed independent Student’s t-tests and also two-way analysis of variances (ANOVA), followed by the Bonferroni post hoc test. The GraphPad Prism 8.02 software was used for statistical testing and graphical data display.

RESULTS

Antiviral activity

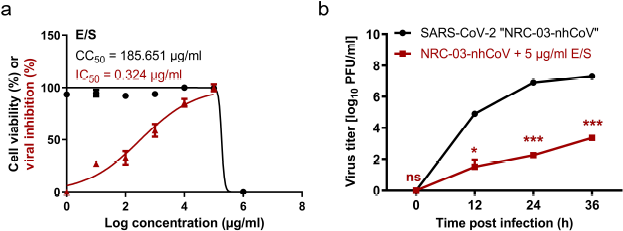

The half-maximal cytotoxic concentration (CC50) of L. cuprina maggots’ E/S was measured (185.651 µg/ml) to determine the appropriate concentration to identify the antiviral activity. E/S showed potential antiviral activity against SARS-CoV-2 with an IC50 of 0.324 µg/ml and a high selectivity index (SI) value of 572.997 (Fig. 1a). The E/S could significantly reduce the growth kinetic of SARS-CoV-2 at 12, 24, and 36 hours p.i. (Fig. 1b).

| Table 1. Primer sequences of target genes. [Click here to view] |

PPI prediction

The PSOPIA prediction tool for PPI showed that L. cuprina maggots’ serine protease present in E/S could interact with TMPRSS2 and cathepsin B (prediction scores 0.88 and 0.95, respectively). These scores are calculated using the PSOPIA platform based on the protein sequence and 3D structure. Other proteins showed lower prediction scores.

Interactions between the studied Notch pathway genes are displayed in Fig. 2a (PPI enrichment p value: 0.00189). Functional enrichments include Notch signaling involved in heart development (GO: 0061314, FDR 0.0009) and positive regulation of neuroblast proliferation (GO:0002052, FDR 0.001).

The protein network of the studied genes shows that the predicted functional partners are neural Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome protein (WASL), actin-related protein 2/3 complex subunit 3, SUMO-activating enzyme subunit 2 (UBA2), and adenomatous polyposis coli protein (cadherin-1) (prediction score 0.9999, Fig. 2b).

Effect of SARS-CoV-2 and E/S on Notch pathway genes

Data from RT-PCR demonstrated that SARS-CoV-2 infection resulted in a significant overexpression of Notch1, Notch2, CTNNB1, PSEN1, and CDC42 at 24 hours after infection. At time intervals 6 and 12 hours, the change in expression of all genes was insignificant compared to control. The L. cuprina E/S was able to significantly downregulate Notch1, Notch2, CTNNB1, PSEN1, and CDC42 in SARS-CoV-2-infected cells at time point 24 hours, shifting their expression toward the control levels (p value < 0.0001 except for CDC42 where p value = 0.0035) (Fig. 3).

| Figure 1. Anti-SARS-CoV-2 activity of E/S. (a) Cytotoxicity and viral inhibition. (b) Virus titer with and without E/S at 12, 24, and 36 hours post infection. Statistical analysis was performed using two-way ANOVA, followed by the Bonferroni post hoc test. The significant differences are indicated (* = p < 0.05, ** = p < 0.01, *** = p < 0.001, and nonsignificant = ns). [Click here to view] |

| Figure 2. PPI and PPI network of the study genes (a and b, respectively). [Click here to view] |

Also, Notch signaling downstream genes, BCL9 and ACTR2, were investigated. Consequently, SARS-CoV-2 overexpressed the BCL9 gene and underexpressed the ACTR2 gene 24 hours after infection of cells. Lucilia cuprina E/S significantly downregulated both genes (p value < 0.0001). However, the relative expression of BCL9 after L. cuprina E/S treatment was significantly lower than its expression levels in control cells.

Effect of SARS-CoV-2 and E/S on SUMO1 and TDG

SARS-CoV-2 infection resulted in a significant overexpression of SUMO1 and TDG after 24 hours of SARS-CoV-2 infection. At 6 and 12 hours after infection, the change in SUMO1 expression was insignificant compared to control. TDG expression was significantly compared to control at 12 hours after infection, and no change in TDG expression was observed after 6 hours of infection.

Treatment of SARS-CoV-2-infected cells with L. cuprina E/S had significantly downregulated SUMO1 and TDG expressions (p value < 0.0001) compared to untreated SARS-CoV-2-infected cells. However, the relative expression of SUMO1 after L. cuprina E/S treatment was still above its expression levels in control cells, while relative expression of TDG after treatment was slightly lower than its expression levels in control cells (Fig. 4).

DISCUSSION

The global pandemic caused by SARS-CoV-2 is currently a target of many studies aiming to prevent viral entry or disease progression. The viral S-protein is responsible for viral entry in host cells through the ACE2/TMPRESS route or the cathepsin route (Chen et al., 2020). In the current study, L. cuprina maggots’ E/S showed potential antiviral activity against SARS-CoV-2 with a high SI value. Similar results were documented for this E/S as an antiviral agent against the Rift valley fever virus and coxsackie B4 virus (Abdel-Samad, 2019). One explanation for this strong effect could be the presence of serine protease in L. cuprina maggots’ E/S. In this study, L. cuprina maggots’ serine protease that presents in E/S was predicted to interact with TMPRSS2 and cathepsin B, raising the possibility that it could compete with the viral S-protein on TMPRSS2 and cathepsin B. Thus, the E/S could be effective against SARS-CoV-2 by inhibiting the two main routes of viral entry.

In the current study, SARS-CoV-2 viral load in VERO-E6 cells treated with L. cuprina E/S was found to be considerably low compared to nontreated cells. This could suggest that the predicted interaction of L. cuprina E/S with TMPRSS2 and cathepsin B could prevent viral entry.

Targeting the interaction between SARS-CoV-2 S-protein and TMPRSS2 is one of the promising approaches in preventing and treating COVID-19. In the same line, a previous study showed that blocking TMPRSS2 using several compounds could inhibit viral entry. One of the TMPRSS2 inhibitors, camostat mesylate, is an FDA-approved drug used to treat pancreatitis, with mild side effects (Hoffmann et al., 2020). However, the cathepsin B endosomal pathway provides an alternative pathway for SARS-CoV-2 entry. At the same time, a previous study had shown that targeting TMPRSS2 and cathepsin B simultaneously is needed to prevent viral entry; cathepsin B inhibitors are still under trial (Padmanabhan et al., 2020).

As L. cuprina E/S is predicted to interact with both TMPRSS2 and cathepsin B in this study and is shown to hinder viral entry, it could provide a promising agent to block the two viral entry pathways simultaneously. Yet, its efficacy needs to be assessed against the camostat mesylate and cathepsin B inhibitors.

Inhibition of viral entry is not sufficient to prevent the progression of COVID-19 infection. As the disease progresses, the viral titer titre may not correlate with the severity of symptoms, especially immune reactions and cytokine storms (Lescure et al., 2020). Hence, studying the effect of L. cuprina E/S on pathways that are related to immunity could provide better insight into its potential clinical usefulness.

| Figure 3. Expression of Notch pathway genes after 24 hours of SARS-CoV-2 infection in vitro (relative to control) and without L. cuprina E/S treatment. Notch1, Notch2, CTNNB1, PSEN1, and CDC42 were significantly downregulated upon treatment (p value < 0.0001 except for CDC42 where p value = 0.0035). [Click here to view] |

| Figure 4. Expression of SUMO1 and TDG after 24 hours of SARS-CoV-2 infection in vitro (relative to control) with and without L. cuprina E/S treatment. SUMO1 and TDG were significantly downregulated upon treatment (p value < 0.0001). [Click here to view] |

Regarding the molecular pathogenesis of SARS-CoV-2, expression of Notch pathway genes, SUMOylation, and TDG was studied. Significant overexpression of Notch1, Notch2, CTNNB1, PSEN1, and CDC42 was observed in SARS-CoV-2 infection. Treatment with L. cuprina E/S significantly downregulates these genes, shifting their expression towards the control levels. The Notch pathway is one of the important pathways that play a major role in innate and adaptive immune cells differentiation and activity (Vieceli Dalla Sega et al., 2019). Inhibition of Notch signaling was reported to affect immune response during viral infection and modulate the immune response to some respiratory viruses (Rizzo et al., 2020).

The Notch pathway and ACE2 and JAK/STAT pathways were reported to be dysregulated in SARS-CoV-2 pathogenesis and related to IL-6 activity (Rizzo et al., 2020). SARS-CoV-2 complications include severe inflammation and cytokine storm. Active Notch signaling has been observed under a variety of inflammatory conditions although the mechanism is not clear yet. In cytokine storm, IL-6 was reported to modulate several signalling signaling cascades, including mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) and Notch pathways (Zhang et al., 2020). Although inhibition of the Notch pathway could decrease antiviral immunity and increase viral load (Ito et al., 2011), it seems that normalization of Notch pathway genes as seen in the current study has opposite effects. The Notch pathway plays multiple roles in cell differentiation and response to infection, and evidence was documented on the role of the Notch pathway in severe COVID-19 complications such as cytokine storm, hypoxemia, and hypercoagulopathy (Breikaa and Lilly, 2021).

The ability of L. cuprina E/S to keep the expression of Notch 1 and Notch 2 near the control levels could suggest a mechanism by which L. cuprina E/S could be effective in the treatment of COVID-19. Previous reports stated that the prevention of Notch signaling pathway activation could interfere with viral entry and pathogenesis (Turshudzhyan, 2020).

Several viruses were reported to be able to evade the immune response by suppressing interferon production. The Wnt pathway was reported to play an important role in regulating immunity. Stabilization of CTNNB1 upon virus infection was proved to negatively regulate the expression of several interferon signaling genes related to innate immunity in a CTNNB1-dependent manner (Baril et al., 2013). In the current study, CTNNB1 was upregulated after SARS-CoV-2 infection, in agreement with a previous study (Vastrad et al., 2020). Lucilia cuprina E/S treatment was able to significantly decrease CTNNB1 expression, even below its levels in control cells. The reason and potential effects of this downregulation need further study.

Presenilin-1 (PSEN-1) is an endoprotease complex that hydrolyzes several transmembrane proteins (Tomita, 2017). It was reported to play a role in the Notch and Wnt signaling cascades and regulation of downstream processes via its role in processing key regulatory proteins (Thompson and Zúñiga-Pflücker, 2011). Hence, PSEN-1 is a part of the gamma-secretase complex that is critical in Notch signaling, and it is involved in the Notch-mediated inflammatory process (Zhou et al., 2015). The gamma-secretase complex is also involved in several neurological disorders (De Strooper et al., 2012). In the current study, PSEN-1 was upregulated after SARS-CoV-2 infection. Its expression levels were lower after treatment with L. cuprina E/S albeit still higher than the control levels. The consequences of SARS-CoV-2-mediated overexpression of PSEN-1 and its potential role in the inflammatory process of COVID-19 need further study. Also, the expression levels of PSEN-1 could help in understanding the previously reported COVID-19-related neurological disorders (Abate et al., 2020).

CDC42 was reported to be involved in the entry process of multiple RNA viruses, including coronaviruses. CDC42 has been also known to affect the cellular cytoskeleton through the formation of lamellipodia, filopodia, and stress fiber (Swaine and Dittmar, 2015). In the current study, CDC24 was overexpressed in SARS-CoV-2-infected cells, and L. cuprina E/S did not return reduce its levels to control levels. The importance of CDC24 in COVID-19 progression remains unclear.

Also, Notch signaling downstream genes, BCL9 and ACTR2, were studied. Herein, SARS-CoV-2 overexpressed the BCL9 gene and underexpressed the ACTR2 gene 24 hours after infection of cells. Lucilia cuprina E/S significantly downregulated both genes, and relative expression of BCL9 after L. cuprina E/S treatment is significantly lower than its expression levels in control cells. BCL9 is known to promote CTNNB1’s transcriptional activity (Adachi et al., 2004). ACTR2 encodes for ARP2 protein that was reported to promote some respiratory viruses’ infection in lung epithelial cell lines. It was found to promote viral gene expression, protein production, viral yield, and cell-to-cell spread (Mehedi et al., 2016).

In the current study, SARS-CoV-2 infection caused significant overexpression of SUMO1 and TDG. This effect was partially prevented by the treatment of SARS-CoV-2-infected cells with L. cuprina E/S that had significantly downregulated SUMO1 and TDG expression. Notably, the relative expression of TDG after treatment with L. cuprina E/S is lower than its expression levels in control cells.

SUMOylation of protein is known to be disrupted in viral infection. Viruses were reported to be able to manipulate the SUMOylation machinery of host cells during virus replication. Some viruses were reported to be able to activate SUMO promoters (Lowrey et al., 2017). SUMO-1 was reported to be dysregulated in SARS-CoV-2 infection (Ibrahim and Ellakwa, 2021). In the current study, SUMO1 was significantly overexpressed in SARS-CoV-2-infected cells; L. cuprina E/S significantly shifted its levels to control levels. Inhibition of SUMO1 could be engaged in the L. cuprina E/S antiviral activity.

SUMOylation signaling was reported to affect the enzyme TDG which was reported to be involved in interferon response to some viral infections (Woodby et al., 2018). TDG was found to be overexpressed in the current study in SARS-CoV-2-infected cells. Lucilia cuprina E/S decreases its levels slightly below the control levels. The SUMO1 ability to stimulate TDG (Smet-Nocca et al., 2011) could provide one explanation for to the increased TDG expression after SARS-CoV-2 infection. On the other hand, increased TDG activity was shown to cause cell death through increasing double-strand breaks, and SUMOylation of TDG appears to play a protective role against cytotoxic double-strand breaks (Steinacher et al., 2019). The interplay between SUMO and TDG and their role in COVID-19 need further study.

CONCLUSION

Lucilia cuprina maggots’ E/S could be promising in the prevention of SARS-CoV-2 “NRC-03-nhCoV” cell entry, potentially due to the interaction of its serine protease with host TMPRSS2 and cathepsin B. In addition, L. cuprina E/S minimizes the dysregulation of Notch pathway genes, SUMO1, and TDG caused by the virus. Therefore, E/S could be a potential strong inhibitor for SARS-CoV-2.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors state that they have no conflicts of interest.

FUNDING

There is no funding to report.

ETHICAL APPROVAL

This study does not involve experiments on animals or human subjects.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Mohammad R. K. Abdel-Samad was responsible for conceptualization, resources, methodology, investigation, writing of the original draft and its review and editing, and visualization. Fatma A. Taher contributed to resources and review and editing of the manuscript. Mahmoud Shehata and Noura M. Abo Shama were responsible for investigation. Ahmed Mostafa contributed to methodology, investigation, review and editing of the manuscript, and visualization. Mohamed A. Ali was responsible for resources. Iman H. Ibrahim contributed to resources, methodology, investigation, writing of the original draft and its review and editing, and visualization.

DATA AVAILABILITY

All data generated and analyzed are included within this research article.

PUBLISHER’S NOTE

This journal remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published institutional affiliation.

REFERENCES

Abate G, Memo M, Uberti D. Impact of covid-19 on alzheimer’s disease risk: viewpoint for research action. Healthc, 2020; 8(3):286; http//doi.org/10.3390/healthcare8030286 CrossRef

Abdel-Samad MRK. Antiviral and virucidal activities of Lucilia cuprina maggots’ excretion/secretion (Diptera: Calliphoridae): first work. Heliyon, 2019; 5(11):e02791; http//doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2019.e02791 CrossRef

Adachi S, Jigami T, Yasui T, Nakano T, Ohwada S, Omori Y, Sugano S, Ohkawara B, Shibuya H, Nakamura T, Akiyama T. Role of a BCL9-related β-catenin-binding protein, B9L, in tumorigenesis induced by aberrant activation of Wnt signaling. Cancer Res, 2004; 64(23):8496–501. PMid:15574752; http//doi.org/10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-2254 CrossRef

Baril M, Es-Saad S, Chatel-Chaix L, Fink K, Pham T, Raymond VA, Audette K, Guenier AS, Duchaine J, Servant M, Bilodeau M, Cohen É, Grandvaux N, Lamarre D. Genome-wide RNAi screen reveals a new role of a WNT/CTNNB1 signaling pathway as negative regulator of virus-induced innate immune responses. PLoS Pathog, 2013; 9(6):e1003416. PMid:23785285; http//doi.org/10.1371/journal.ppat.1003416 CrossRef

Breikaa RM, Lilly B. The Notch pathway: a link between COVID-19 pathophysiology and its cardiovascular complications. Front Cardiovasc Med, 2021; 0:528; http//doi.org/10.3389/FCVM.2021.681948 CrossRef

Casu RE, Pearson RD, Jarmey JM, Cadogan LC, Riding GA, Tellam RL. Excretory/secretory chymotrypsin from Lucilia cuprina: purification, enzymatic specificity and amino acid sequence deduced from mRNA. Insect Mol Biol, 1994; 3(4):201–11. PMid:7704304; http//doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2583.1994.tb00168.x CrossRef

Chambers L, Woodrow S, Brown AP, Harris PD, Phillips D, Hall M, Church JCT, Pritchard DI. Degradation of extracellular matrix components by defined proteinases from the greenbottle larva Lucilia sericata used for the clinical debridement of non-healing wounds. Br J Dermatol, 2003; 148 (1):14–23. PMid:12534589; http//doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2133.2003.04935.x CrossRef

Chen N, Zhou M, Dong X, Qu J, Gong F, Han Y, Qiu Y, Wang J, Liu Y, Wei Y, Xia J, Yu T, Zhang X, Zhang L. Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of 99 cases of 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a descriptive study. Lancet, 2020; 395(10223):507–13. PMid:32007143; http//doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30211-7 CrossRef

De Strooper B, Iwatsubo T, Wolfe MS. Presenilins and γ-secretase: structure, function, and role in Alzheimer disease. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med, 2012; 2(1):a006304. PMid:22315713; http//doi.org/10.1101/cshperspect.a006304 CrossRef

Feng Y, Zhao M, He Z, Chen Z, Sun L. Research and utilization of medicinal insects in China. Entomol Res, 2009; 39(5):313–6; http//doi.org/10.1111/j.1748-5967.2009.00236.x CrossRef

Feoktistova M, Geserick P, Leverkus M. Crystal violet assay for determining viability of cultured cells. Cold Spring Harb Protoc, 2016; 2016(4):343–6. PMid:27037069; http//doi.org/10.1101/pdb.prot087379 CrossRef

Gupta A. A review of the use of maggots in wound therapy. Ann Plast Surg, 2008; 60(2):224–7. PMid:18216520; http//doi.org/10.1097/SAP.0b013e318053eb5e CrossRef

Hassan MI, Hammad KM, Fouda MA, Kamel MR. The using of Lucilia cuprina maggots in the treatment of diabetic foot wounds. J Egypt Soc Parasitol, 2014; 44(1):125–9; http//doi.org/10.12816/0006451 CrossRef

Hoffmann M, Kleine-Weber H, Schroeder S, Krüger N, Herrler T, Erichsen S, Schiergens TS, Herrler G, Wu NH, Nitsche A, Müller MA, Drosten C, Pöhlmann S. SARS-CoV-2 cell entry depends on ACE2 and TMPRSS2 and is blocked by a clinically proven protease inhibitor. Cell, 2020; 181(2):271–80.e8. PMid:32142651; http//doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2020.02.052 CrossRef

Ibrahim IH, Ellakwa DES. SUMO pathway, blood coagulation and oxidative stress in SARS-CoV-2 infection. Biochem Biophys Reports, 2021; 26:100938. PMid:33558851; http//doi.org/10.1016/j.bbrep.2021.100938 CrossRef

Ito T, Allen RM, Carson IV WF, Schaller M, Cavassani KA, Hogaboam CM, Lukacs NW, Matsukawa A, Kunkel SL. The critical role of Notch ligand delta-like 1 in the pathogenesis of influenza a virus (H1N1) infection. PLoS Pathog, 2011; 7(11):e1002341. PMid:22072963; http//doi.org/10.1371/journal.ppat.1002341 CrossRef

Jacobs AL, Schär P. DNA glycosylases: in DNA repair and beyond. Chromosoma, 2012; 121(1):1–20. PMid:22048164; http//doi.org/10.1007/s00412-011-0347-4 CrossRef

Jiang KC, Sun XJ, Wang W, Liu L, Cai Y, Chen YC, Luo N, Yu JH, Cai DY, Wang AP. Excretions/secretions from bacteria-pretreated maggot are more effective against Pseudomonas aeruginosa Biofilms. PLoS One, 2012; 7(11):e49815. PMid:23226221; http//doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0049815 CrossRef

Kandeil A, Mostafa A, El-Shesheny R, Shehata M, Roshdy WH, Ahmed SS, Gomaa M, Taweel AE, Kayed AE, Mahmoud SH, Moatasim Y. Coding-complete genome sequences of two SARS-CoV-2 isolates from Egypt. Microbiol Resour Announc, 2020; 9(22). PMid:32467284; http//doi.org/10.1128/mra.00489-20 CrossRef

Kandeil A, Mostafa A, Hegazy RR, El-Shesheny R, Taweel A El, Gomaa MR, Shehata M, Elbaset MA, Kayed AE, Mahmoud SH, Moatasim Y, Kutkat O, Yassen NN, Shabana ME, Gaballah M, Kamel MN, Shama NMA, Sayes M El, Ahmed AN, Elalfy ZS, Mohamed BMSA, Abd El-Fattah SN, Hariri HM El, Kader MA, Azmy O, Kayali G, Ali MA. Immunogenicity and safety of an inactivated sars-cov-2 vaccine: preclinical studies. Vaccines, 2021; 9(3):1–15; http//doi.org/10.3390/vaccines9030214 CrossRef

Kawase M, Shirato K, van der Hoek L, Taguchi F, Matsuyama S. Simultaneous treatment of human bronchial epithelial cells with serine and cysteine protease inhibitors prevents severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus entry. J Virol, 2012; 86(12):6537–45. PMid:22496216; http//doi.org/10.1128/jvi.00094-12 CrossRef

Keewan E, Naser SA. The role of notch signaling in macrophages during inflammation and infection: implication in rheumatoid arthritis? Cells, 2020; 9(1):111. PMid:31906482; http//doi.org/10.3390/CELLS9010111 CrossRef

Khare P, Sahu U, Pandey SC, Samant M. Current approaches for target-specific drug discovery using natural compounds against SARS-CoV-2 infection. Virus Res, 2020; 290:198169. PMid:32979476; http//doi.org/10.1016/j.virusres.2020.198169 CrossRef

Lescure FX, Bouadma L, Nguyen D, Parisey M, Wicky PH, Behillil S, Gaymard A, Bouscambert-Duchamp M, Donati F, Le Hingrat Q, Enouf V, Houhou-Fidouh N, Valette M, Mailles A, Lucet JC, Mentre F, Duval X, Descamps D, Malvy D, Timsit JF, Lina B, van-der-Werf S, Yazdanpanah Y. Clinical and virological data of the first cases of COVID-19 in Europe: a case series. Lancet Infect Dis, 2020; 20(6):697–706. PMid:32224310; http//doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30200-0 CrossRef

Loram A. Book review: the insects: an outline of entomology. J Insect Conserv, 2006; 10(1):81–2; http//doi.org/10.1007/s10841-005-8782-2 CrossRef

Lowrey AJ, Cramblet W, Bentz GL. Viral manipulation of the cellular sumoylation machinery. Cell Commun Signal, 2017; 15(1). PMid:28705221; http//doi.org/10.1186/s12964-017-0183-0 CrossRef

Lu Y, Zhang Y, Xiang X, Sharma M, Liu K, Wei J, Shao D, Li B, Tong G, Olszewski MA, Ma Z, Qiu Y. Notch signaling contributes to the expression of inflammatory cytokines induced by highly pathogenic porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus (HP-PRRSV) infection in porcine alveolar macrophages. Dev Comp Immunol, 2020; 108:103690. PMid:32222356; http//doi.org/10.1016/J.DCI.2020.103690 CrossRef

Mahmoud DB, Shitu Z, Mostafa A. Drug repurposing of nitazoxanide: can it be an effective therapy for COVID-19? J Genet Eng Biotechnol, 2020; 18(1). PMid:32725286; http//doi.org/10.1186/s43141-020-00055-5 CrossRef

Masucci MG. Viral ubiquitin and ubiquitin-like deconjugases— swiss army knives for infection. Biomolecules, 2020; 10(8):1–24. PMid:32752270; http//doi.org/10.3390/biom10081137 CrossRef

Mehedi M, McCarty T, Martin SE, Le Nouën C, Buehler E, Chen YC, Smelkinson M, Ganesan S, Fischer ER, Brock LG, Liang B, Munir S, Collins PL, Buchholz UJ. Actin-related protein 2 (ARP2) and virus-induced filopodia facilitate human respiratory syncytial virus spread. PLoS Pathog, 2016; 12(12):e1006062. PMid:27926942; http//doi.org/10.1371/journal.ppat.1006062 CrossRef

Mostafa A, Kandeil A, Elshaier YAMM, Kutkat O, Moatasim Y, Rashad AA, Shehata M, Gomaa MR, Mahrous N, Mahmoud SH, Gaballah M, Abbas H, Taweel A El, Kayed AE, Kamel MN, Sayes M El, Mahmoud DB, El-Shesheny R, Kayali G, Ali MA. Fda-approved drugs with potent in vitro antiviral activity against severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2. Pharmaceuticals, 2020; 13(12):1–24; http//doi.org/10.3390/ph13120443 CrossRef

Murakami Y, Mizuguchi K. Homology-based prediction of interactions between proteins using Averaged One-Dependence Estimators. BMC Bioinform, 2014; 15(1). PMid:24953126; http//doi.org/10.1186/1471-2105-15-213 CrossRef

Nigam Y, Bexfield A, Thomas S, Ratcliffe NA. Maggot therapy: the science and implication for CAM Part I - History and bacterial resistance. Evid Based Compl Altern Med, 2006; 3(2):223–7; http//doi.org/10.1093/ecam/nel021 CrossRef

Padmanabhan P, Desikan R, Dixit NM. Targeting TMPRSS2 and Cathepsin B/L together may be synergistic against SARSCoV- 2 infection. PLoS Comput Biol, 2020; 16(12):e1008461. PMid:33290397; http//doi.org/10.1371/journal.pcbi.1008461 CrossRef

Payne S. Methods to study viruses. Viruses, 2017: 37–52; http//doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-803109-4.00004-0 CrossRef

Petersen H, Mostafa A, Tantawy MA, Iqbal AA, Hoffmann D, Tallam A, Selvakumar B, Pessler F, Beer M, Rautenschlein S, Pleschka S. NS segment of a 1918 influenza a virus-descendent enhances replication of H1N1pdm09 and virus-induced cellular immune response in mammalian and avian systems. Front Microbiol, 2018; 9(MAR); http//doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2018.00526 CrossRef

Pöppel AK, Koch A, Kogel KH, Vogel H, Kollewe C, Wiesner J, Vilcinskas A. Lucimycin, an antifungal peptide from the therapeutic maggot of the common green bottle fly Lucilia sericata. Biol Chem, 2014; 395(6):649–56. PMid:24622788; http//doi.org/10.1515/hsz-2013-0263 CrossRef

Pytel D, S?upianek A, Ksiazek D, Skórski T, B?asiak J. Uracil-DNA glycosylases. Postepy Biochem, 2008; 54(4):362–70. PMid:19248582; http//doi.org/10.1016/b978-0-12-821067-3.00039-8 CrossRef

Ragia G, Manolopoulos VG. Inhibition of SARS-CoV-2 entry through the ACE2/TMPRSS2 pathway: a promising approach for uncovering early COVID-19 drug therapies. Eur J Clin Pharmacol, 2020; 76(12):1623–30. PMid:32696234; http//doi.org/10.1007/s00228-020-02963-4 CrossRef

Rizzo P, Vieceli Dalla Sega F, Fortini F, Marracino L, Rapezzi C, Ferrari R. COVID-19 in the heart and the lungs: could we “Notch” the inflammatory storm? Basic Res Cardiol, 2020; 115(3). PMid:32274570; http//doi.org/10.1007/s00395-020-0791-5 CrossRef

Ryu HY. SUMO: a novel target for anti-coronavirus therapy. Pathog Glob Health, 2021:1–8; http//doi.org/10.1080/20477724.2021.1906562

Sherman RA. Maggot therapy takes us back to the future of wound care: new and improved maggot therapy for the 21st century. J Diabetes Sci Technol, 2009; 3(2):336–44. PMid:20144365; http//doi.org/10.1177/193229680900300215 CrossRef

Smet-Nocca C, Wieruszeski JM, Léger H, Eilebrecht S, Benecke A. SUMO-1 regulates the conformational dynamics of Thymine-DNA Glycosylase regulatory domain and competes with its DNA binding activity. BMC Biochem, 2011; 12(1):4. PMid:21284855; http//doi.org/10.1186/1471-2091-12-4 CrossRef

Steinacher R, Barekati Z, Botev P, Ku?nierczyk A, Slupphaug G, Schär P. SUMOylation coordinates BERosome assembly in active DNA demethylation during cell differentiation. EMBO J, 2019; 38(1). PMid:30523148; http//doi.org/10.15252/embj.201899242 CrossRef

Swaine T, Dittmar MT. CDC42 use in viral cell entry processes by RNA viruses. Viruses, 2015; 7(12):6526–36. PMid:26690467; http//doi.org/10.3390/v7122955 CrossRef

Szklarczyk D, Gable AL, Lyon D, Junge A, Wyder S, Huerta-Cepas J, Simonovic M, Doncheva NT, Morris JH, Bork P, Jensen LJ, Von Mering C. STRING v11: protein-protein association networks with increased coverage, supporting functional discovery in genome-wide experimental datasets. Nucleic Acids Res, 2019; 47(D1):D607–13. PMid:30476243; http//doi.org/10.1093/nar/gky1131 CrossRef

Thompson PK, Zúñiga-Pflücker JC. On becoming a T cell, a convergence of factors kick it up a Notch along the way. Semin Immunol, 2011; 23(5):350–9. PMid:21981947; http//doi.org/10.1016/j.smim.2011.08.007 CrossRef

Tomita T. Probing the structure and function relationships of presenilin by substituted-cysteine accessibility method. Meth Enzymol, 2017; 584:185–205. PMid:28065263; http//doi.org/10.1016/bs.mie.2016.10.033 CrossRef

Turshudzhyan A. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2)-induced cardiovascular syndrome: etiology, outcomes, and management. Cureus, 2020; 12:e8543; http//doi.org/10.7759/cureus.8543. CrossRef

Vastrad B, Vastrad C, Tengli A. Identification of potential mRNA panels for severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (COVID-19) diagnosis and treatment using microarray dataset and bioinformatics methods. 3 Biotech, 2020; 10(10):422; http//doi.org/10.1007/s13205-020-02406-y CrossRef

Van der Plas MJA, Jukema GN, Wai SW, Dogterom-Ballering HCM, Lagendijk EI, Van Gulpen C, Van Dissel JT, Bloemberg G V., Nibbering PH. Maggot excretions/secretions are differentially effective against biofilms of Staphylococcus aureus and Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Antimicrob Chemother, 2008; 61(1):117–22. PMid:17965032; http//doi.org/10.1093/jac/dkm407 CrossRef

Vieceli Dalla Sega F, Fortini F, Aquila G, Campo G, Vaccarezza M, Rizzo P. Notch signaling regulates immune responses in atherosclerosis. Front Immunol, 2019; 10(MAY). PMid:31191522; http//doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2019.01130 CrossRef

Vistnes LM, Lee R, Ksander GA. Proteolytic activity of blowfly larvae secretions in experimental burns. Surgery, 1981; 90(5):835–41. PMid:7029766; http//doi.org/10.1097/00006534-198205000-00122

Woodby BL, Songock WK, Scott ML, Raikhy G, Bodily JM. Induction of interferon kappa in human papillomavirus 16 infection by transforming growth factor beta-induced promoter demethylation. J Virol, 2018; 92(8):e01714–7. PMid:29437968; http//doi.org/10.1128/jvi.01714-17 CrossRef

Zhang C, Wu Z, Li JW, Zhao H, Wang GQ. Cytokine release syndrome in severe COVID-19: interleukin-6 receptor antagonist tocilizumab may be the key to reduce mortality. Int J Antimicrob Agents, 2020; 55(5):105954. PMid:32234467; http//doi.org/10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2020.105954 CrossRef

Zhou M, Cui Z lei, Guo X jun, Ren L pin, Yang M, Fan Z wen, Han R chao, Xu W guo. Blockade of Notch signalling by γ-secretase inhibitor in lung T cells of asthmatic mice affects T cell differentiation and pulmonary inflammation. Inflammation, 2015; 38(3):1281–8. PMid:25586485; http//doi.org/10.1007/s10753-014-0098-5 CrossRef