INTRODUCTION

The international community recognizes that the state must guarantee the protection and empowerment of married couples in family planning services. Reproductive management is considered as the main means of maintaining health and belongs to the category of fundamental human rights, according to key international documents (World Health Organization, 2015a).

Today, the improvement of reproductive management is based on the “patient-centered” principle and includes the study of the consumer and their desires, possibilities, and adherence to a particular type of contraception (compliance). However, modern scientists argue that the price factor of contraceptives is the main obstacle when using reproductive management (Braun and Grever, 2020). To sum up, it is clear that the consumer price research, namely, the psychological price (the price that a person is willing to pay for a specific product which depends on the personality of the consumer, their position in life, the need for a product, etc.), remains a fundamental step in improving family planning services (World Health Organization, 2018).

The classical methods of studying psychological prices and willingness to pay are divided into three groups. The first two groups (historical analysis of data about consumer behavior and the discrete choice experiment) are economic. They tend to become outdated and require a significant amount of information about the market and financial resources. This is the main barrier to their widespread practical application. The third group includes marketing direct surveys. These marketing studies make it possible to interpret and integrate the basic provisions of economic theory into the process of making price decisions (Monroe, 1973). They form the main knowledge base about consumer pricing: interrelation between price and quality, price, and utility (value), the perception of prices depending on brands, the influence of factors on pricing, studying psychological prices, buyer segmentation based on the external or internal reference prices, and others (Dickson and Sawyer, 1973; Manoj and Menon, 2007; Shapiro,1968, 1973; Yin and Paswan, 2007; Zeithaml, 1987).

Focusing on the above problems (increasing compliance and overcoming the price barrier for women), the key remains to determine the subjective willingness to pay by women, which can be done using methods of setting psychological prices from scientific marketing methods. Determination of the psychological price, and hence the willingness to pay, is based on the postulate formed by marketing scientists about the existence of a “standard price” (Gabor and Granger, 1986; Mazumdar et al., 2005; Stoetzel, 1986). According to market studies, the “standard price” (optimal price) is a point on the consumer’s subjective scale, below which the price of a product is extremely cheap and above which it is extremely expensive (Winer, 1986).

The theoretical substantiation of this hypothesis is borrowed from the field of psychology and some other theories. In the adaptation theory of Helson (1964), individual processes of generating judgments are forms of adaptation to external and internal stimuli (Helson, 1964). Helson (1964) experimentally confirmed the existence of a “personal scale,” “standard (optimal) and neutral (indifferent) points” in humans. Against these points, the consumer makes the assessment. At the same time, as Emery (1970) showed, around the optimal price an area of tolerance or indifference is formed (Herrmann et al., 2004). This zone has been interpreted as an area of price fluctuations relative to the reference (optimal price), and these do not have a sharp impact on the level of compliance (Sinha and Prasad, 2004). We can call this high point of consumer’s indifference the indifference price.

These theories, as well as the theory of assimilation and contrasts, the theory of range, and the theory of cognitive dissonance, underlie and confirm the validity of using marketing methods based on the optimal and indifference prices for estimating willingness to pay (Festinger, 1964; Volkmann, 1951).

One such method is Van Westendorp’s method. Another name for this method is price sensitivity measurement (PSM) (Van Westendorp, 1976).

The simplicity of calculations and interpretation of results and relative cheapness of this method’s implementation distinguish it (Kunter, 2016; Wildner, 2003). In addition, Van Westendorp (1976) refers to several more psychophysical theories: the Weber-Fechner theory and the theory of reasonable prices (Kamen and Toman, 1970). However, they all describe a similar mechanism for estimating and setting an optimal price to which the consumer subconsciously agrees.

Despite its widespread use in many countries, PSM is rarely used in Ukrainian marketing practice and is absent in the pharmaceutical sector (Podolchak and Gavrylyuk, 2013; Salamandic et al., 2014). These facts, along with the importance of the family planning process for the state as a whole and the woman’s compliance, including in economic terms, to the chosen method of contraception, determine the relevance and expediency of using this method in pharmaceutical practice.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Sample design

We conducted a cross-sectional study based on a quota sample, which consisted of 420 women of reproductive age (World Health Organization, 2021) from the Zaporizhzhia region, Ukraine. The size of the quota sample was justified by the requirements for the PSM study, sociological research on the possibility of using a quota sample that corresponds to or exceeds the calculated random sample for the general population (N = 384,369; n = 384) (Dobrenkov and Kravchenko, 2003; Zhurko and Zenkova, 2016). The main so?ial and economic criteria for inclusion in the sample were age, per capita income, and women’s education. Data on quota volumes by indicators were obtained from the State Statistics Service of Ukraine (Appendix Table A1).

According to the age indicator, seven quotas were formed: 16–19 years (n = 29), 20–24 years (n = 42), 25–29 years (n = 60), 30–34 years (n = 78), 35–39 years (n = 73), 40–44 years (n = 70), and 45–49 years (n = 68). Based on age quotas, quotas were formed according to the level of per capita income: income up to 88 EUR, 20.7% of the age quota; from 88 to 129 EUR, 34.3%; and more than 129 EUR, 45% of the age quota.

Further, the quotas were divided into the smallest shares by the level of education: the quota of respondents with higher education/planning to obtain higher education was 47.1% and without higher education (school, college, or technical school)/do not plan to receive higher education 52.9%. This approach to age gradation and the distribution of per capita income quotas was based on methodological frameworks for conducting sociological research, ethical and legal norms in Ukraine, and assumptions about the mandatory existence of the middle sociological class in any society (Myagkov,1996).

Experiment design

To establish the psychological prices of women and willingness to pay for contraceptives, women were asked four questions regarding each contraceptive (Van Westendorp, 1976):

- At which price on this scale you are beginning to experience (test-product) as too cheap—so that you say at this price the quality cannot be good?

- At which price on this scale are you beginning to experience (test-product) as cheap?

- At which price on this scale are you beginning to experience (test-product) as expensive?

- At which price on this scale you are beginning to experience (test-product) as too expensive—so that you would never consider buying it yourself?

The anonymous questionnaire survey was conducted as a hall test (a special method of field marketing research, both qualitative and quantitative, involving interviews with a relatively large number of respondents using a special questionnaire in a designated closed room for the purpose of testing, including comparative, certain properties of the product). Such face-to-face contact helps to increase the reliability of the results of the psychological survey method, according to sociological studies.

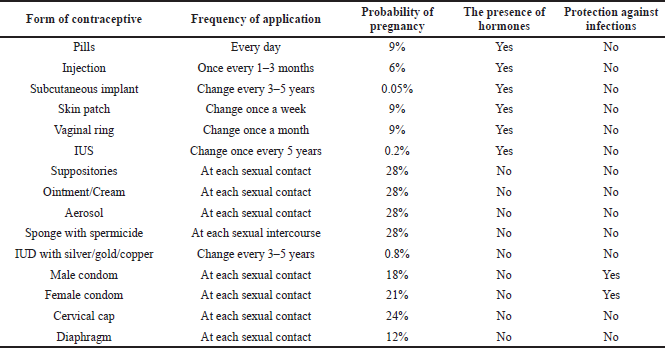

Previously, the women were provided with information (name, image, frequency and duration of use, and level of protection) on the main means of contraception for their detailed acquaintance (Appendix Table A2). The list of tested contraceptives was formed based on regulatory legal documents in the field of women’s health and included the following (World Health Organization, 2015b):

- a) Hormonal contraceptives: pills, injections, subcutaneous implants, skin patches, vaginal rings, and intrauterine therapeutic systems (IUSs).

- b) Nonhormonal medicinal contraceptives: vaginal suppositories, vaginal creams/ointments, vaginal aerosols, and sponges with contraceptive.

- c) Contraceptive medical devices: intrauterine devices (IUDs) with silver/gold/copper, male and female condoms, cervical caps, and diaphragms.

For each of the four questions, a set of prices was proposed that ranged from 0% of the maximum market price to 100% in 20% increments in monetary terms in UAH (Ukrainian currency in the ISO 4217 standard) for each contraceptive (prices have been converted to euros for clarity) (Appendix Table A3). The definition of the maximum market price as the upper limit value of the price is associated with the peculiarities of the implementation of the programs of assistance to the population “Affordable Medicines” and the accompanying marketing research on this topic. Information on market prices was obtained from the online drug reference service “Tabletki.ua” and “Compendium.com.ua”.

This price division allows using the obtained data about willingness to pay in the process of price modeling in special social family planning programs and in the pharmaceutical market of Ukraine.

Statistical analysis

Data were entered and analyzed using the MS Excel 2010 software.

The prices according to questions 1–4 were considered as random variables ?j, j = 1,4 with the corresponding distribution functions Fj(x) = P(Xj<x). The results of the questionnaire were presented as a four-dimensional sample (?q1, ?q2, ?q3, ?q4), where q = 1,2…N (number of women interviewed separately to independent sample elements).

For each vector of the sample {?1j, ?1j…. ?1N} of random variable ?j, j = 1,4, empirical cumulative distribution functions were constructed:

where I[0,x)— indicator function.

Empirical cumulative survival functions were also constructed for the price distribution functions (1, 2 questions):

*Sj(x) = 1-*Fj(x),

where

*F1 are empirical cumulative distribution functions for question 1,

*F2 are empirical cumulative distribution functions for question 2,

*F3 are empirical cumulative distribution functions for question 3,

*F4 are empirical cumulative distribution functions for question 4,

*S1 are empirical cumulative survival functions for question 1,

*S2 are empirical cumulative survival functions for question 2.

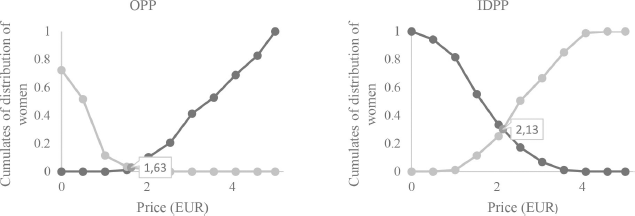

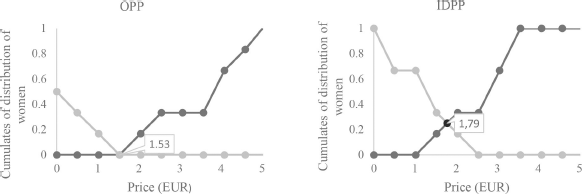

The results of the calculation of the empirical distribution and survival functions are reflected on a graph.

To calculate the values of the point of indifference (IDPP) and optimal price point (OPP), the method of piecewise linear approximation was used, where for all distribution curves the following was observed:

*Fj(x) = a+bx+? ; 0≤ x≤ xmax

*Sj(x) = a+bx+?; 0≤ x≤ xmax,

where

a is a constant or intercept term,

? is the standard error.

For the obtained regression models, the coefficient of determination R2 and F-test were calculated. The regression equations were considered valid when R2?0.90 and Fest. ? Ftab., p ? 0.05.

The IDPP and OPP values at the point of intersection of the regression curves were found from the following equality:

*Fj(x) = *Sj(x)

The value of the point of intersection of the regression curves *S2 and *F3 is the IDPP and *S1 and *F4 OPP. The recommended range of willingness to pay is the interval between the points of the optimal price (reference price) and the point of indifference price.

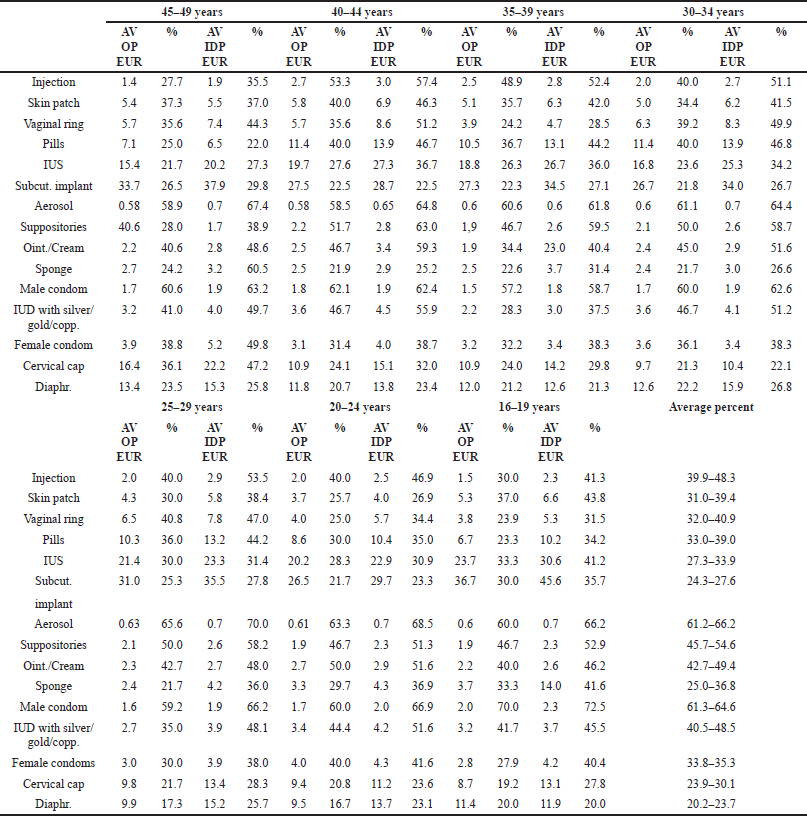

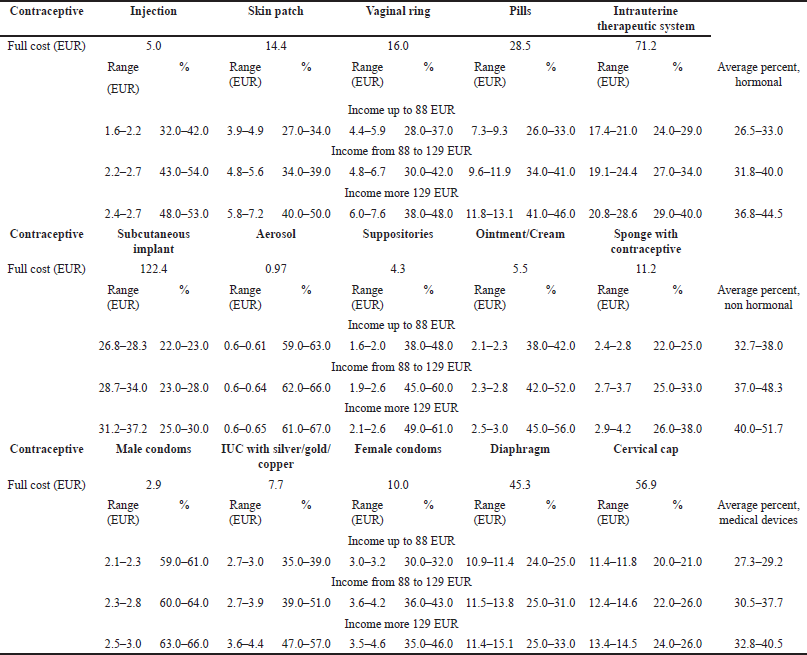

At the first stage of the study, willingness to pay for contraceptives was determined in per capita income quotas. Two graphs of the cumulative distribution of respondents were constructed for each contraceptive (15 items/90 graphs), in accordance with three income quotas (up to 88 EUR, from 88 to 129 EUR, and more than 129 EUR) (Fig. 1 shows, as an example, the graphs of the cumulative distribution of women for injectable contraceptives in the income group up to 88 EUR). Point values of the OPP and IDPP were calculated (Table 1).

| Figure 1. Graphs of cumulative distribution functions of women for injectable contraceptives in the income quota up to 88 EUR. [Click here to view] |

| Table 1. Ranges of willingness to pay by per capita income quotas. [Click here to view] |

| Figure 2. Graphs of cumulative distribution functions of women for injectable contraceptives in the income quota up to 88 EUR of 16–19 years old. [Click here to view] |

At the second stage of the study, willingness to pay for contraceptives was determined in age quotas.

Two graphs of the cumulative distribution of respondents were constructed for each contraceptive (15 items/630 graphs), in accordance with three income quotas (up to 88 EUR, from 88 to 129 EUR, and more than 129 EUR) and seven ages quotas (Fig. 2 shows, as an example, the graphs of the cumulative distribution of women for injectable contraceptives in the income quota up to 88 EUR of 16–19-year-olds). Point values of the OPP and IDPP were calculated (Table 2).