INTRODUCTION

To be established as a new drug candidate in the drug discovery process, a bioactive compound must have all of the desirable pharmacokinetic properties in all dimensions of the potent drug. Many plant-based bioactive compounds, despite having bioactive potential, fail to progress to the stage of becoming a potent drug in terms of its bioactivity. Drug resistance, as well as the use of multiple drugs for the treatment of single health problem, has changed researchers’ interest toward multi-target drugs in the treatment and management of complex diseases over the years. Physicochemical properties along with absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion, and toxicity (ADMET) properties of a compound define the effectiveness of a compound in relation to its solubility, permeability, and metabolic stability which mainly affect oral bioavailability, metabolism, clearance, toxicity, etc. (Bocci et al., 2017; Daina et al., 2017).

Throughout the drug development phase, small molecules with bioactive principles have to possess the ability to reach the specified target in their bioactive form with an effective concentration to attain their in-vitro bioactive potential which is mainly dependent on their pharmacokinetic and toxicity properties. Hence, an early evaluation of the compound’s physicochemical, ADMET properties, as well as target and biological activity prediction through in-silico studies would help to eliminate or reduce unnecessary efforts of in-vivo screening, identifying novel therapeutic targets, and drug leads. In the case of multifactorial disease conditions, like chronic inflammation and cancer that depend on multiple mediators to advance, it will be highly advantageous if they can be managed effectively by a multitarget drug candidate (Koeberle and Werz, 2014).

Lignans and neolignans are well documented for a wide range of bioactivities such as antioxidant, antitumor, anti-inflammatory, anti-neurodegenerative, antiviral, and antimicrobial properties. The fact that in the past 7 years 564 different lignans and neolignans have been discovered from natural sources highlights their significance in drug development (Teponno et al., 2016; Zálešák et al., 2019). Our earlier study had identified Fragransol B, a lignan from bioactive methanol extracts of leaves and bark of Myristica dactyloides with antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties (Marulasiddaswamy et al., 2021), has not been evaluated individually for any bioactive potential to date; it has only been identified from Myristica fragrans extracts evaluated for antimicrobial activity (Hada et al., 1988; Hattori et al., 1988). Although Fragransol B has been earlier characterized and identified mainly from M. fragrans, a well-established plant species in the Myristicaceae family with a wide variety of activities attributed to it, (Abourashed and El-Alfy, 2016; Asgarpanah, 2012; Kuete, 2017), limited attention has been received from the scientific community to validate its pharmaceutical potential. Hence, there is a need to validate its pharmaceutical potential and develop it as a drug candidate for the management of pathophysiology of inflammatory conditions. Fragransol B (2,3-dihydro-5-(2″-hydroxyethyl)-2-(4′hydroxy-3′-methoxyphenyl)-7-methoxy-3-methylbenzofuran) a phenylpropanoid containing the dihydrobenzofuran moiety, consist of 2-aryl-3-methyl-2,3-dihydrobenzofurans with one benzylic methine, one hydroxymethyl, two methoxyl, and five aromatic protons (Hada et al., 1988).

With this background, the current research was focused on the comprehensive in-silico evaluation of Fragransol B for the physicochemical and the ADMET properties of this compound were also assessed to ensure its candidature as an effective drug candidate. Furthermore, its anti-inflammatory efficiency was evaluated by employing protein–ligand docking studies against a set of proinflammatory targets. In addition, efforts were also made to predict the target as well as the prediction of biological activity of this compound.

MATERIALS AND METHOD

Chemical structure preparation for in-silico studies

The structure files for Fragransol B (PubChem ID: 14015413), a bioactive molecule identified from the methanol extracts of leaves and bark of M. dactyloides (Marulasiddaswamy et al., 2021), along with standard anti-inflammatory drugs Diclofenac (PubChem ID: 3033) and Celecoxib (PubChem ID: 2662), were retrieved in “.sdf” and “.mol” file formats from the public chemical database—PubChem (https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/).

Physicochemical properties and ADME parameters

Physicochemical Properties, lipophilicity, water solubility, pharmacokinetics, drug-likeness, and medicinal chemistry parameters are well-established parameters of the drug discovery process to characterize an effective drug candidate. These parameters were examined using SwissADME, an online web-based method (http://www.swissadme.ch/index.php) (Daina et al., 2017). The algorithm computes properties such as molecular weight, fraction Csp3, RB, no. of H bond acceptors, no. of H bond donors, MR, TPSA, water solubility Log Se [Estimated SOLubility (ESOL)], lipophilicity Qlog Po/w, and drug likeness—Lipinski (RO5) violation, bio-availability score along with lead likeness— rule of three (RO3) violation. Pharmacokinetic parameters like human gastrointestinal absorption [GI (HIA)], blood–brain barrier permeation (BBB), permeability glycoprotein (P-gp), cytochrome P450 inhibitor (CYP), and skin permeability coefficient (Log Kp) are also evaluated.

Assessment of toxicity of Fragransol B

Early evaluation of a compound’s toxicity for harmful effects on humans, animals, plants, and the environment is very essential for the development of a new drug candidate and significantly reduces the necessity of animal models for the evaluation along with cost reduction. The algorithm computes the toxicity for various toxicity endpoints, such as acute toxicity, hepatotoxicity, cytotoxicity, carcinogenicity, mutagenicity, immunotoxicity, adverse outcomes pathways (Tox21), and toxicity targets, based on the molecular similarity, pharmacophores, different fragments in the molecular structure of the compounds. Fragransol B’s toxicity was assessed using the ProTox-II web server for a variety of toxicity endpoints (hepatotoxicity, immunotoxicity, genetic toxicity endpoints, especially cytotoxicity, mutagenicity, and carcinogenicity) (Banerjee et al., 2018).

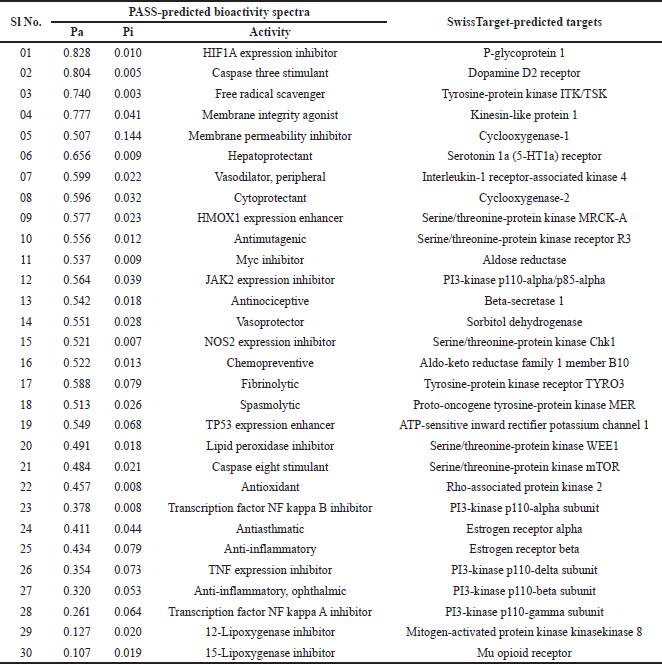

Biological activity prediction of Fragransol B

The PASS online, an in-silico server for the prediction of biological properties and possible targets, was used to investigate Fragransol B’s biological activity spectrum. PASS algorithm with a training set of over 260,000 drug-like biologically active compounds (drugs, drug candidates, lead compounds, and toxic compounds) simultaneously predicts 3,678 kinds of activity (95% mean accuracy) based on multilevel neighbors of atoms descriptors of the molecular structures of active compounds in comparison with the training set. The ratios of “probability to be active (Pa)” and “probability to be inactive (Pi)” were used to predict and rank biological properties. A higher “Pa” indicates higher probability of a compound to be bioactive (Lagunin et al., 2000).

Ligand-based target prediction of Fragransol B

Understanding the likely targets of an active compound early during the drug discovery process would aid in the repurposing of the compound for various bioactive potentials. The SwissTargetPrediction tool, which primarily predicts targets based on ligand-based screening in comparison with known compiled in curated, cleansed collections of known actives, was used to investigate possible protein targets of the chosen phytochemical through ligand-based screening (Daina et al., 2019). The query molecule can be uploaded as SMILES or through drawing in MarvinJS molecular editor, and after selecting a species from Homo sapiens, Mus musculus, and Rattus norvegicus, the targets can be predicted.

Anti-inflammatory molecular docking studies to predict the best fit

Inflammation is a complex condition that needs a multitarget drug to control since different proinflammatory mediators participate in the disease’s progression to chronic conditions. The Protein Data Bank (PDB; https://www.rcsb.org) was used to retrieve the X-ray crystallography structures of proinflammatory targets such as Lipoxygenase-3 (Soybean) complex with epigallocatechin (PDB ID:1JNQ), human secretory phospholipase A2 (sPLA2) (PDB ID:1POE), structure of celecoxib bound COX-2 (PDB ID:3LN1), Stable-5-LOX in complex with arachidonic acid (PDB ID:3V99), cyclooxygenase-1 in complex with celecoxib (PDB ID:3KK6), nitric oxide synthase (NOS) (PDB ID:5UO1), Salicylate bound to human cyclooxygenase-2 (PDB ID:5F1A), and tumour necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) (PDB ID:2AZ5). The anti-inflammatory mode of action of Fragransol B along with the standard anti-inflammatory drugs Diclofenac, and Celecoxib was determined using Schrodinger’s Maestro platform (Version 11.2).

Preparation of proteins targets

Selected X-ray crystallography structures of different proinflammatory targets for this study were refined using the Protein Preparation Wizard tool. Initially, proteins were preprocessed by assigning bond orders, followed by the addition of hydrogens, creating the disulfide bonds and modifications. Furthermore, protein structures were refined by optimizing hydrogen bond assignment using PROPKA for which pH was adjusted to 7 ± 2. Restrained minimization was used to minimize non-hydrogen atoms by default root-mean-square deviation to 0.3Å with the OPLS3 force field (Madhavi Sastry et al., 2013). Finally, the refined structures were used for the ligand-target GLIDE docking process.

Preparation of ligands

In the docking analysis, in-silico molecular interactions of Fragransol B and the positive controls Diclofenac, and Celecoxib with various inflammatory targets were studied. The ligands were prepared beforehand using the LigPrep tool to produce all possible tautomers and stereoisomers, as well as three-dimensional (3D) coordinates. The OPLS3 force field was used to minimize energy and the possible states were generated using Epik at pH 7 ± 2. All the generated stereoisomers were used for the GLIDE docking process (Balakumar et al., 2010; Madhavi Sastry et al., 2013).

GLIDE docking

The GLIDE docking module was used to assess the interaction between selected ligands and proinflammatory targets. All refined proteins were given a receptor gird box based on the ligand and ligands were docked using the GLIDE docking module’s extra-precision (XP) mode. The binding affinity of the ligand expressed as XP score (kcal/mol) was used to determine the anti-inflammatory potential of the phytochemicals (Friesner et al., 2004; Joshi et al., 2016).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Small molecules derived from various natural sources showing tremendous bioactive potential during in-vitro evaluation often fail to pass the drug development process since they struggle to maintain the same effect when it comes to in-vivo conditions. This is due to their physicochemical and ADMET properties that play a significant role in determining the efficacy of the

drug candidate (Banerjee et al., 2018; Daina and Zoete, 2016; Daina et al., 2017). The prime aim of this investigation was to validate the anti-inflammatory potential of Fragransol B using protein–ligand docking experiments against a wide range of proinflammatory targets and to evaluate its physicochemical and ADMET properties. In addition, efforts were also made to find its possible targets and to predict its biological activity(ies) (Daina et al., 2019; Lagunin et al., 2000).

Fragransol B belongs to lignans and neolignans class of compounds known for various bioactive properties highlighting their importance in the field of drug development (Teponno et al., 2016; Zálešák et al., 2019). With this in mind, the research was planned to evaluate this compound through in silico tools for further development as a drug candidate. As per our knowledge, there have been no studies on the bioactive potential of Fragransol B.

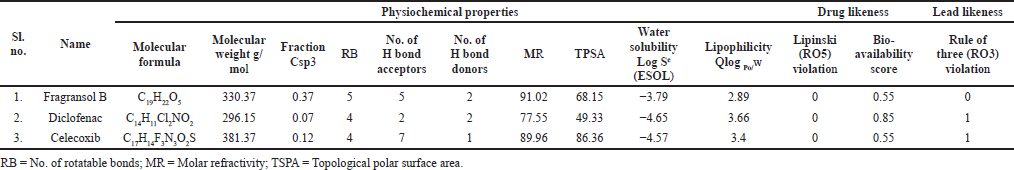

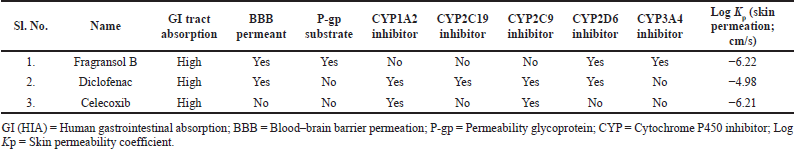

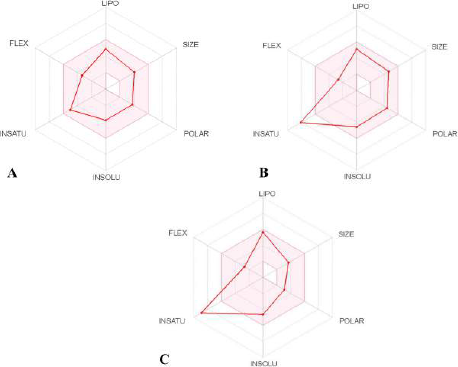

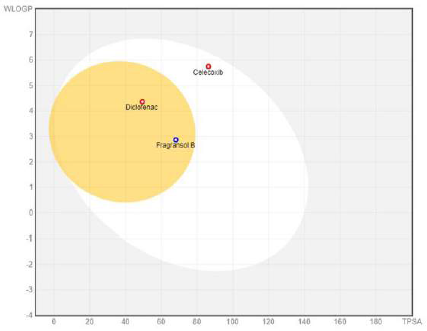

The physiochemical properties, drug and lead-likeness parameters, and pharmacokinetic parameters of Fragransol B evaluated through SwissAMDE are summarised in Tables 1 and 2. Fragransol B is falling within Lipinski’s rule and bioavailability radar (Fig. 1). The bioavailability of the compound under the biological system plays an important role in its effectiveness with respect to its target, which is primarily based on oral bioavailability. This is predominantly addressed by six major physicochemical properties of the molecule: lipophilicity, size, polarity, solubility, flexibility, and saturation. Score of TPSA analysis highlighted the effective oral absorption efficiency of Fragransol B and proves the passive absorption of the molecule by GI tract. In addition, BOILED EGG model analysis indicates the ability of Fragransol B to penetrate the blood–brain barrier through the central nervous system by P-glycoprotein (PGP+) (Fig. 2) (Daina and Zoete, 2016). It is interesting to note that these properties of Fragransol B are similar to the standards Diclofenac and Celecoxib used in the study. The drug’s effectiveness is governed by its ability to reach its target at the right dosage, which is determined primarily by lipophilicity, size, polarity, solubility, flexibility, and saturation. As a result, these parameters play an important role in the drug’s binding to its target.

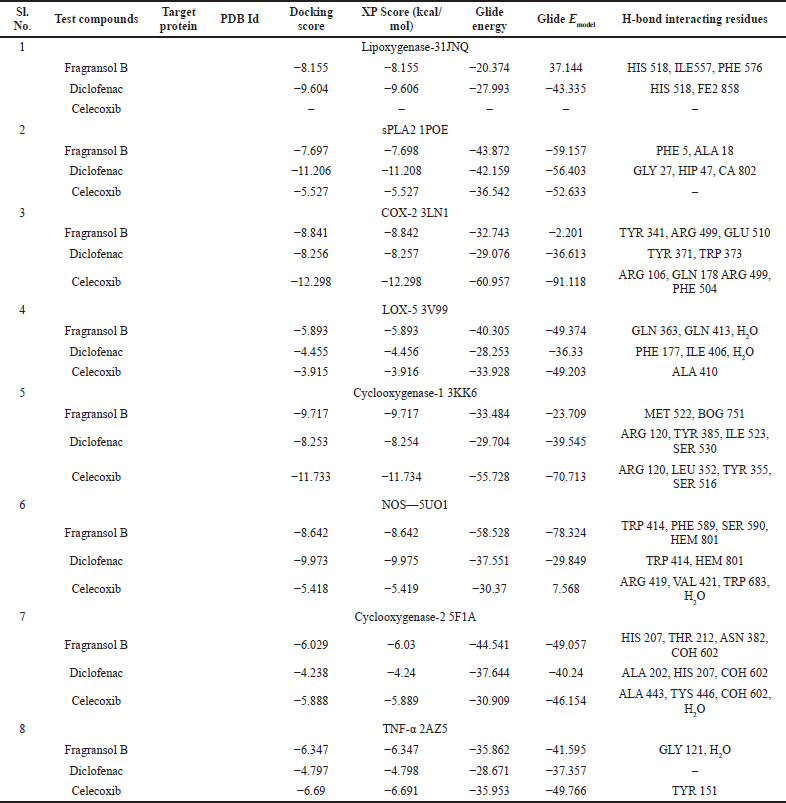

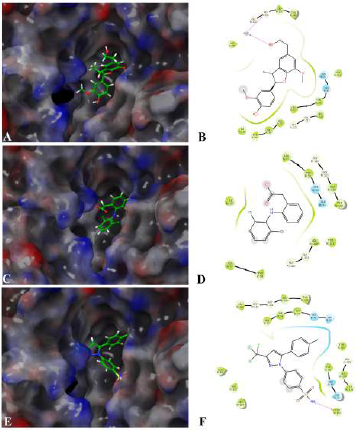

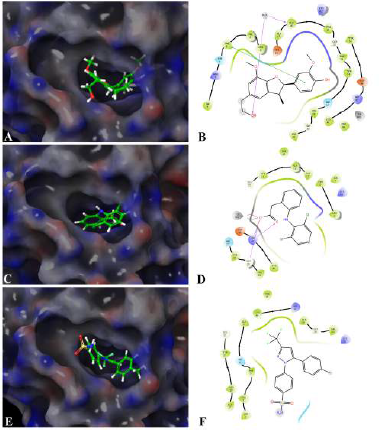

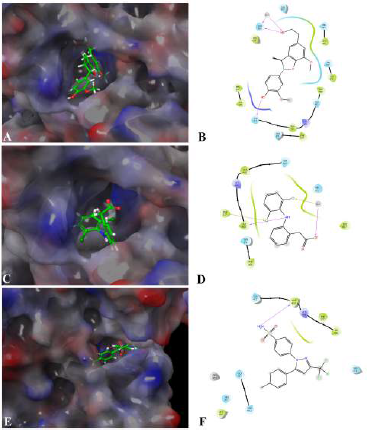

Assessing the toxicity of a compound for different toxicity endpoints is very critical for the drug development process since it will minimize the risks during animal studies and clinical evaluation. The toxicity of the compound and the LD50 value indicates that Fragransol B belongs to Class IV with an LD50 −1,743 mg/kg and has shown only immunotoxicity. The effect of Fragransol B on different proinflammatory targets was evaluated through in-silico molecular interaction studies. Table 3 summarizes the interaction of Fragransol B with the various proinflammatory targets indicating the XP score (kcal/ mol) and H-bond interacting residues. The binding affinity of Fragransol B was favored by hydrogen-bond interaction with the inflammatory marker enzyme Lipoxygenase-3 residues HIS 518, ILE 557, and PHE 576 with XP score (kcal/mol) −8.155. This offers a strong case for future investigation to unveil its efficacy in treating asthma, inflammation, arthritis, and psoriasis (Kühn et al., 2005). It is well known that phospholipase A2 plays a significant role in systemic and acute inflammatory conditions (Balsinde et al., 1999). However, there is a dearth of natural specific PLA2 inhibitors, due to which there is a continuous interest in finding new pharmacologic inhibitors to treat various inflammatory disorders. In this context, the interaction of Fragransol B with Human sPLA2 (−7.697 kcal/mol) by hydrogen bond formation with residues PHE 5 and ALA 18 demonstrated in the present study appears to be particularly potent in inhibition of PLA2. Fragransol B also exhibited notable binding affinity with COX-2 when assessed with celecoxib bound COX-2 3LN1 (−8.841 kcal/ mol), by hydrogen bond formation with amino acid residues TYR 341, ARG 499, and GLU 510 which act as an entry point for the COX-2 active site. These results add TYR 341, ARG 499, and GLU 510 to the list of previously cataloged COX-2 active site amino acid residues (Llorens et al., 1999).

The interaction between Fragransol B and LOX-5 through hydrogen interactions with residues—GLN 363 and GLN 413—has a strong binding affinity with this enzyme (XP score = −5.893 kcal/mol). It was observed that the positive standards Diclofenac and Celecoxib were comparatively less competitive in establishing strong affinity with the active site of LOX-5 compared to Fragransol B highlighting its higher efficiency in inhibiting this enzyme (Table 3 and Fig. 6). Among all the test targets, the binding affinity of Fragransol B with the binding pocket of cyclooxygenase-1 was found to be very high (−9.717 kcal/mol) favored by hydrogen-bond interactions with residues MET 522 and BOG 751. NOS is another important target enzyme with which Fragransol B showed significant interaction in the present study by binding to the active site TRP 414, and other residues PHE 589, SER 590, and HEM 801 through hydrogen bonding (XP score = −8.642 kcal/mol). Finding new inhibitor molecules for TNF-α has considerable therapeutic potential in treating various diseases including cancer (Zia et al., 2020). Our analysis recorded an XP score of −6.347 kcal/mol for the interaction of Fragransol B with this target protein. Several earlier studies have set an XP value greater than −6.5 kcal/mol as a cut-off score for further experimental consideration of the molecule as a drug candidate (Table 3 and Fig. 6) (Zia et al., 2020). Thus, our results highlight the possible role of Fragransol B in treating diseases influenced by the dysregulation of TNF-α.

Among the tested proinflammatory targets used in the present investigation, the maximum inhibitory interaction by Fragransol B was observed with COX-1, followed by COX2, LOX-3, Nos, and PLA-2 enzymes. Minimum inhibition was observed with TNF-α and LOX-5. Binding modes and molecular interactions of Fragransol B, Diclofenac, and Celecoxib with Lipoxygenase-3, Secretory Phospholipase, and cyclooxygenase-2 are shown in Figures 4–6.

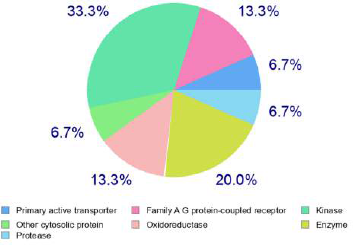

The anti-inflammatory potential conferred by docking studies is well supported through the in-silico bioactivity spectra prediction and target prediction mainly based on the structure similarity screening. Table 4 and Figure 3 show the different probable targets and bioactive potential with emphasis given to the anti-inflammatory potential of the compound. The compound shows probable inhibitory effects on NOS 2 expression, Transcription factor NF kappa B, TNF expression, transcription factor NF kappa A, 12-Lipoxygenase, 15-Lipoxygenase, Cyclooxygenase-1, and Cyclooxygenase-2, demonstrating its potential as an anti-inflammatory drug candidate.

| Table 1. Physiochemical properties, drug and lead-likeness parameters of the Fragransol B, Diclofenac, and Celecoxib. [Click here to view] |

| Table 2. Pharmacokinetic parameters of the Fragransol B, Diclofenac, and Celecoxib. [Click here to view] |

| Figure 1. Bioavailability radar of (A) Fragransol B, (B) Celecoxib, and (C) Diclofenac with a pink area representing the optimal range for each property (lipophilicity: XLOGP3 between −0.7 and + 5.0; size: MW between 150 and 500 g/mol; polarity: TPSA between 20 and 130 Å2; solubility: log S not higher than 6; saturation: fraction of carbons in the sp3 hybridization not less than 0.25; and flexibility: no more than nine rotatable bonds). [Click here to view] |

| Figure 2. BOILED-egg plot representing the passive gastrointestinal absorption (HIA) and BBB of the compound. [Click here to view] |

| Table 3. Binding mode and molecular interaction of Fragransol B, Diclofenac, and Celecoxib with proinflammatory targets. [Click here to view] |

| Figure 3. Different classes of predicted targets of the Fragransol B. [Click here to view] |

| Figure 4. Binding mode and molecular interaction of selected compounds with [Click here to view] |

| Figure 5. Binding mode and molecular interaction of selected compounds with Human sPLA2 (PDB ID:1POE). (A and B) Fragransol B, (C and D) Diclofenac, and (E and F) Celecoxib. [Click here to view] |

| Figure 6. Binding mode and molecular interaction of selected compounds with LOX-5 (3V99). (A and B) Fragransol B, (C and D) Diclofenac, and (E and F) Celecoxib. [Click here to view] |

| Table 4. Predicted bioactivity spectra of Fragransol B depicting different bioactivities and probable targets. [Click here to view] |

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONS STATEMENT

All the authors have made substantive intellectual contributions to the content of this manuscript in the following areas: concept and design—KMM and KRK; data acquisition and analysis—KMM; drafting manuscript—KMM, SCR, BRN, and KRK; critical revision of manuscript SNB, BRN, and SS; and

supervision and final approval—KRK.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors were financially supported through the UGC: National Fellowship for Higher Education (NFHE) for this study. We thank Department of Studies in Computer Science, University of Mysore for providing Schrodinger’s Maestro software (Version 11.2). The authors are thankful to the Sophisticated Analytical Instrument Facility (SAIF), IIT Bombay instrumentation facility. The authors are also grateful to the Institution of Excellence (IOE), University of Mysore, for the instrumentation facility.

ETHICAL APPROVAL

Not applicable.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors have declared no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

Abourashed EA, El-Alfy AT. Chemical diversity and pharmacological significance of the secondary metabolites of nutmeg (Myristica fragrans Houtt.). Phytochem Rev, 2016; 15:1035–56; https://doi.org/10.1007/s11101-016-9469-x CrossRef

Asgarpanah J. Phytochemistry and pharmacologic properties of Myristica fragrans Hoyutt.: a review. Afr J Biotechnol, 2012; 11:12787–93; https://doi.org/10.5897/AJB12.1043

Balakumar C, Lamba P, Kishore DP, Narayana BL, Rao KV, Rajwinder K, Rao AR, Shireesha B, Narsaiah B. Synthesis, anti-inflammatory evaluation and docking studies of some new fluorinated fused quinazolines. Eur J Med Chem, 2010; 45:4904–13. CrossRef

Balsinde J, Balboa MA, Insel PA, Dennis EA. Regulation and inhibition of phospholipase A2. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol, 1999; 39:175–89; https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.39.1.175

Banerjee P, Eckert AO, Schrey AK, Preissner R. ProTox-II: A webserver for the prediction of toxicity of chemicals. Nucleic Acids Res, 2018; 46:W257–63; https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gky318

Bocci G, Carosati E, Vayer P, Arrault A, Lozano S, Cruciani G. ADME-Space: A new tool for medicinal chemists to explore ADME properties. Sci Rep, 2017; 7:25–7; https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-01706692-0

Daina A, Michielin O, Zoete V. SwissADME: a free web tool to evaluate pharmacokinetics, drug-likeness and medicinal chemistry friendliness of small molecules. Sci Rep, 2017; 7:42717; https://doi.org/10.1038/srep42717

Daina A, Michielin O, Zoete V. SwissTargetPrediction: updated data and new features for efficient prediction of protein targets of small molecules. Nucleic Acids Res, 2019; 47:W357–664; https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkz382

Daina A, Zoete V. A BOILED-egg to predict gastrointestinal absorption and brain penetration of small molecules. Chem Med Chem, 2016; 11:1117–21; https://doi.org/10.1002/cmdc.201600182

Friesner RA, Banks JL, Murphy RB, Halgren TA, Klicic JJ, Mainz DT, Repasky MP, Knoll EH, Shelley M, Perry JK, Shaw DE, Francis P, Shenkin PS. Glide: a new approach for rapid, accurate docking and scoring. 1. Method and assessment of docking accuracy. J Med Chem, 2004; 47:1739–49; https://doi.org/10.1021/jm0306430

Hada S, Hattori M, Tezuka Y, Kikuchi T, Namba T. New neolignans and lignans from the aril of Myristica fragrans. Phytochemistry, 1988; 27:563–8; https://doi.org/10.1016/0031-9422(88)83142-X

Hattori M, Yang XW, Shu YZ, Kakiuchi N, Tezuka Y, Kikuchi T, Namba T. New constituents of the aril of Myristica fragrans. Chem Pharm Bull, 1988; 36:648–53. CrossRef

Joshi V, Venkatesha SH, Ramakrishnan C, Nanjaraj Urs AN, Hiremath V, Moudgil KD, Velmurugan D, Vishwanath BS. Celastrol modulates inflammation through inhibition of the catalytic activity of mediators of arachidonic acid pathway: secretory phospholipase A2 group IIA, 5-lipoxygenase and cyclooxygenase-2. Pharmacol Res, 2016; 113:265–75; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.phrs.2016.08.035

Koeberle A, Werz O. Multi-target approach for natural products in inflammation. Drug Discov Today, 2014; 19:1871–82; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drudis.2014.08.006

Kuete V. 2017. Myristica fragrans: a review. Medicinal spices and vegetables from Africa. Therapeutic potential against metabolic, inflammatory, infectious and systemic diseases, pp 497–512. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-809286-6.00023-6

Kühn H, Römisch I, Belkner J. The role of lipoxygenaseisoforms in atherogenesis. Mol Nutr Food Res, 2005; 49:1014–29. CrossRef

Lagunin A, Stepanchikova A, Filimonov D, Poroikov V. PASS: prediction of activity spectra for biologically active substances. Bioinformatics, 2000; 16:747–8; https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/16.8.747

Llorens O, Perez JJ, Palomer A, Mauleon D. Structural basis of the dynamic mechanism of ligand binding to cyclooxygenase. Bioorg Med Chem Lett, 1999; 9:2779–84. CrossRef

Madhavi Sastry G, Adzhigirey M, Day T, Annabhimoju R, Sherman W. Protein and ligand preparation: parameters, protocols, and influence on virtual screening enrichments. J Comput Aided Mol Des, 2013; 27:221–34; https://doi.org/10.1007/s10822-013-9644-8

Marulasiddaswamy KM, Nuthan BR, ChannarayapatnaRamesh S, Bajpe SN, Kumara KKS, Sekhar SKK. HRLC-MS based profiling of phytochemicals from methanol extracts of leaves and bark of Myristica dactyloides Gaertn. from Western Ghats of Karnataka, India. J Appl Biol Biotech, 2021;9(05):124–135.

Teponno RB, Kusari S, Spiteller M. Recent advances in research on lignans and neolignans, Nat Prod Rep, 2016; 33(9):1044–92; https://doi.org/10.1039/c6np00021e

Zálešák F, Bon DJYD, Pospíšil J. Lignans and neolignans: plant secondary metabolites as a reservoir of biologically active substances. Pharmacol Res, 2019; 146:104284; https://doi.org/10.1016/j.phrs.2019.104284

Zia K, Ashraf S, Jabeen A, Saeed M, Nur-e-Alam M, Ahmed S, Al-Rehaily AJ, Ul-Haq Z. 2020. Identification of potential TNF-α inhibitors: from in silico to in vitro studies. Sci Rep, 2020; 10: 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-77750-3