INTRODUCTION

Regarding bioequivalence, two pharmaceutical products are considered to be bioequivalent in their bioavailabilities (rate and extent) and efficacies if they are administered in identical amounts of the same active substance(s), similar dosage forms, and same route of administration and if they display comparable properties (Dunne et al., 2013). Therefore, generic drugs are permitted by regulators based on evidence of pharmaceutical equivalence and bioequivalence with the originator counterparts. The excipients of the originator and generic drugs are not necessarily similar, which may affect the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics parameters of the drug and its safety profile. According to the World Health Organization, a generic drug is a pharmaceutical product that is produced by a manufacturer without a license from the patent-holding company and marketed when the original patent has expired, which means that they do not need the originator company’s approval to produce a generic drug (Dunne et al., 2013; US Food and Drug Administration, 2013). Also, they contain equivalent quantities and qualities of the same active substance(s) and the same pharmaceutical form as their reference original drugs, with low-cost price, and may contain different excipients (Desai et al., 2019; Kesselheim et al., 2008; Vogler, 2012). However, bioequivalence and the role of excipients may be elucidated regarding the clinical efficacy and safety when switching from originator to generic formulations. Cost-benefits, purchasing, and prescription behaviors can explain the choice between generic and originator counterparts (Gallelli et al., 2013). The use of generic drugs is trending upward in the upcoming years, accounting for approximately 90% of all prescriptions drug in the US (Desai et al., 2019). The definitive aim of generic drug production is to enhance the global access and regulation of generic drugs and to preclude drug shortages and supply disturbances (Håkonsen and Toverud, 2019). Likewise, many consumers and providers recognize generic drugs to be less effective and less safe than their originator counterparts (Kesselheim et al., 2016). These negative expectations may affect patients to experience negative clinical results while using generic drugs (Desai et al., 2019). Once the generic drug enters the market, an increase in cost savings is highly probable. In comparison to the originator, the use of generic drugs has a significant economic benefit in controlling healthcare spending and saving money for society. Thus, a true economic cost must be carefully considered before switching a drug, taking into account the clinical outcomes of the generic medication for any individual patient (Dunne et al., 2013; Johnston et al., 2010; Olsson and Sporrong, 2012).

In 2005, a health economic study examined the possible cost savings for the substitution of originator drugs with generic drugs based on data collected from 1997 to 2000. It showed that generic substitutions could save up to 5.9 billion dollars for populations younger than 65 years old and 2.9 billion dollars for populations older than 65 years old (Haas et al., 2005; Rizzo and Zeckhauser, 2009). Thus, generic drugs offer healthcare systems considerable cost savings; however, their acceptance is stalled by worries of physicians and patients about the efficacy and safety of these drugs (Tian et al., 2020). Many factors can affect the prescriptions/purchasing behavior of the bioequivalent medication (Rizzo and Zeckhauser, 2009). Physicians are the eventual decision-makers of which drug brands should be prescribed to their patients. Therefore, all the marketing strategies are being directed toward them (Ahmed et al., 2020; Shamim-ul-Haq et al., 2014). Their decisions have a profound impact on the quantity, quality, and costs of healthcare systems (Mohammadshahi et al., 2019). There are specific factors that affect the prescription attitude of physicians such as a new drug in the market, brand prescription, sponsorship to conferences, promotional tools, and free drug samples (Shamim-ul-Haq et al., 2014). Shamim-ul-Haq et al. (2014) suggest that new drugs, promotional tools, and drug samples significantly effluence the prescription behavior of physicians, and the remaining factors do not have any major effect. Originator products are always expensive compared to local products; consequently, the brand prescription is less effective on the prescription behavior of physicians due to the cost factor, whereas Raheem Ahmed et al. (2020) concluded that marketing elements (such as the brand of the drug, sales promotion, availability of drug information, medical representatives’ effectiveness, patient’s characteristics including their expectations and request for a particular drug, and pharmacist factors) have a positive and massive influence on the decision of physician to prescribe a drug. Furthermore, physician’s habits and the cost-benefit ratio of the medicine have played a substantial moderating effect to prescribe a specific drug. Physicians are more willing to prescribe generic medications when a medical representative of a generic company visits them many times per month and provides them with sufficient information and upgrades about the generic drug (Shamim-ul-Haq et al., 2014).

On the other hand, the characteristics of the drug do not have any moderating influence on the expectations of patients and the decisions of physicians to prescribe the drug. Similarly, trustworthiness has a significant control impact on pharmacist–-physician cooperation, the pharmacists’ expertise, and the decision of physicians to prescribe a drug (Schumock et al., 2004). Therefore, the financial incentives of the consumers and physician’s influence play important roles in consumer purchasing patterns of prescription drugs (Kohli and Buller, 2013). The main purpose of this research was to understand what factors impact consumers’ purchasing/prescription patterns of generic drugs versus originator drugs and to add sufficient knowledge based on consumer preference (Rizzo and Zeckhauser, 2009). Additionally, the aim was to investigate the role of healthcare professionals specifically physicians and pharmacists in the acceptance of generic drugs since they create the ultimate decision on what to prescribe and dispense. Also, the purpose of this research was to display the roles of healthcare professionals in persuading patients whose confidence in generic drugs often rests on the appropriate information provided by health specialists (Håkonsen and Toverud, 2019).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design

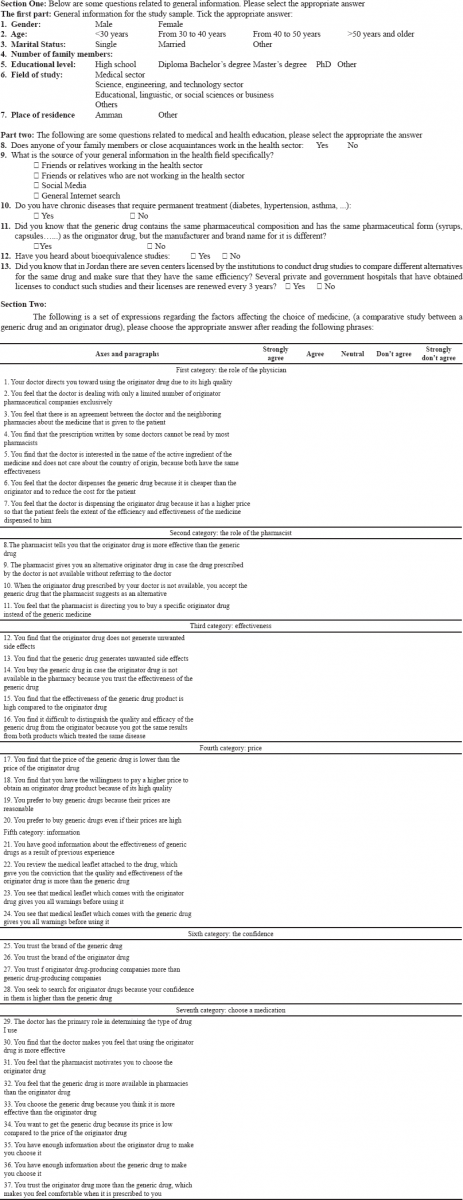

This study was conducted in Jordan from March to October of 2020. Google Form surveys were used to investigate the factors affecting the choice between originator drugs and generic drugs (Al-Samydai et al., 2020). A simple random sampling strategy was used to collect data. Three hundred and four people were recruited and their demographic data have also been reported. To ensure the quality of the survey, we set the response range of some items (e.g., age, marital state, academic qualification, and field of study). Finally, a total of 304 people who completed the questionnaires (which contained 37 questions as shown in Appendix Table 1) were included in the analysis (Al-Samydai et al., 2020).

Study model

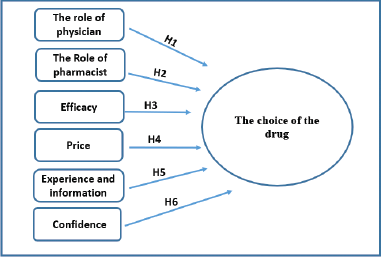

Figure 1 shows the study model which contains the study research problem, objectives, and hypotheses (Al-Samydai et al., 2019; Yousif and Al-samydai, 2019). The hypothesis of this study is to investigate the impact of independent factors (the role of physician, the role of pharmacist, efficacy, price, experience, and confidence) on the dependent factor (choice of the drug).

Statistical analysis

The study aimed to document the impact of several factors affecting the choice of the drug. Therefore, bivariate correlation analysis, linear regression, two-sample t-test, and one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) were conducted using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences® software, version 21 (Aburjai et al., 2019). Values of p ≤ 0.05 are considered to be significant.

| Figure 1. Study model; the factors affecting the choice of the originator drug versus generic drug. (H1): there is an impact of physician role on the choice of the drug, (H2): there is an impact of pharmacist role on the choice of the drug, (H3): there is an impact of efficacy on the choice of the drug, (H4): there is an impact of price on the choice of the drug, (H5): there is an impact of experience and information on the choice of drug, and (H6): there is an impact of confidence on the choice of the drug. [Click here to view] |

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

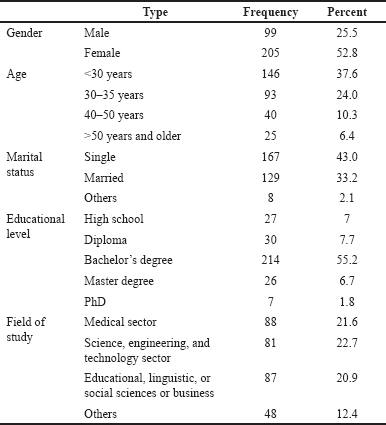

Although the use of generic drugs has augmented promptly in the past two decades, many negative observations may lead patients to switch back to the branded product after generic substitution. Indeed, switching back to the branded product is highly prevalent and their role in educating the patients about drugs’ safety, effectiveness, price, and quality may affect patients’ perceptions (Desai et al., 2019; Kesselheim et al., 2016). Table 1 shows the demographic distribution of study samples.

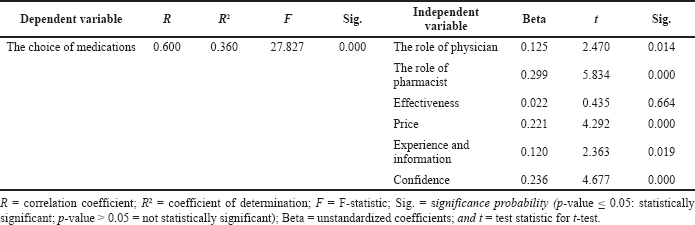

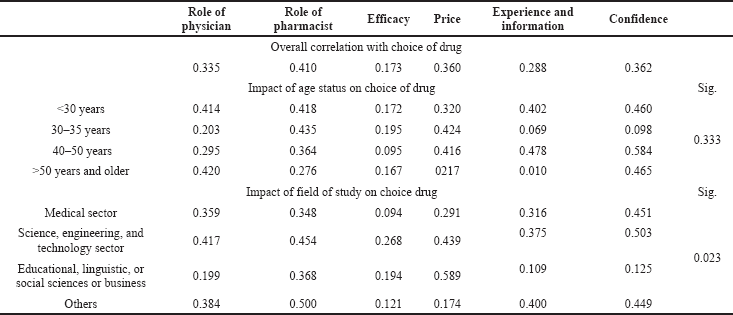

The general drug purchasing patterns of Jordanian individuals and the factors affecting their drug choice were tested based on data collected from a random sample of the Jordanian population. Table 2 shows the multiple regression analyses between the role of physicians, the role of pharmacists, efficacy, price, experience and information, and confidence in the choice of medications. Table 2 also shows that the research-dependent variables (choice of medications) are significant because the p-value is 0.000 which is < 0.05, and the calculated F-value is 27.827, which is more than the table F-value (2.372). Therefore, we reject the null hypothesis and accept the alternative one which states that there is a statistically significant effect at the level of α ≤ 0.05 of the role of physicians, the role of pharmacists, efficacy, price, experience and information, and confidence on the choice of drugs. The relationship between dependent and independent variables is strong and positive. It is > 0.5 (Cohen, 1999), R = 0.600. Also, R2 = 0.360, which means that the contribution of the independent variables strongly affects the dependent variables with a percentage of 36.0% since the value of the calculated t for the variables (the role of physician: 2.470; the role of the pharmacist: 5.834; price: 4.292; experience and information: 2.363; and confidence: 4.677) is more than the table t-value (1.96). This means that they have a statistically significant effect on the choice of medications, while the t-value of the efficacy was 0.435, which was less than the table t-value (1.96), which means that the efficacy does not have a statistically significant effect on the choice of medications. The role of a pharmacist is considered one of the main factors affecting drug choice, which plays a critical role in using generic or originator counterparts. Table 3 shows that the independent factors (effectiveness, experience and information, the role of physician, price, confidence, and role of the pharmacist) and dependent variable (the choice of medications) had significant positive linear relationships of 0.173, 0.288, 0.335, 0.360, 0.362, and 0.410, respectively.

| Table 1. Demographic distribution of the study samples. [Click here to view] |

One-way ANOVA was carried out to test the effect of the field of study on the choice of medications. The results show that there was a significant difference, which means that the field of study has an impact on the choice of medications with p = 0.023. Science and humanity field respondents showed the highest positive correlations between dependent and independent variables, while medical field respondents showed a negative correlation. The main factors affecting the preference for purchasing generic drugs were the socioeconomic factor (Guttier et al., 2017) and this was compatible with several studies that suggested that generic competition affects branded- prices and market shares (Aronsson et al., 2001), and there is a strong dynamic relationship between consumer trust and product loyalty (Alhabeeb, 2007), where consumers’ confidence in the product characteristics, especially those related to knowledge about generic drugs, plays an important role in choosing the product. Concerning age, there were no differences in the preference of generic and branded drugs. In terms of education, nine nonmedical field respondents or less educated individuals were more affected by the pharmacist and physician’s opinions toward generic and branded- drugs. Information from pharmaceutical companies increases awareness of available medicines in the market (Davari et al., 2018). Also, Quintal and Mendes (2012) carried out a research on medicine use and pharmacists’ counseling; it was observed that the lack of information received by the user, lack of prescription, and absence of confidence in generic medicines were the main reasons for the underuse of generic drugs. However, after recognizing the specific knowledge about price and having better knowledge about generic drugs, users had a higher preference for purchasing them. A previous study conducted by Keenum et al. (2012), which has concluded that most respondents agreed that generic drugs were inexpensive (98%), was as effective as the branded medicine (77%), and had no problem in replacement with generic ones (80%), but only 45% preferred generic drugs over the originator counterparts. Nardi and Ferraz (2016) concluded that the price is an important factor that may contribute to the decision to purchase generic drugs. And those who showed a lower effect on the preference for generic drugs were efficacy and experience, in comparison to the healthcare system’s role that showed a higher effect. Thus, raising awareness on the quality of generic drugs in healthcare professionals and consumers was the best approach, especially that a physician has no direct pecuniary incentives to choose less expensive products or overall to inform himself/herself about generic alternatives (Aronsson et al., 2001). Patient admittance to harmless and profitable treatment became a main priority in the healthcare system. The development of bioequivalent drugs in comparison to original drugs has become an interesting topic to both the industry and society to reduce healthcare costs, fulfill the needs of healthcare sponsors, possibly grow availability to patients, and patient and physician acceptance, with numerous patients choosing biologics and branded products. Also, physicians prescribing the same limits the use of generic medicine and bioequivalence. The growth of generic products depend on sponsors’ decisions to provide or use these products safely and selflessly (Ibrahim and Awaisu, 2020). Known factors affecting people’s behaviors toward purchasing generic drugs versus originators will play an impotent role for many companies to put strategies based on the market and help other companies to enter the marketplace.

| Table 2. Results of multiple regressions of the first main hypothesis. [Click here to view] |

| Table 3. Correlations (Pearson’s correlation) between independent factors and dependent factors. [Click here to view] |

CONCLUSION

The use of generic drugs is trending upward; their usage increases in several countries due to the lower price compared to their originator counterparts while maintaining the same efficacy. The results revealed that the most influential factor for participants when purchasing drugs was the pharmacist’s role. On the contrary, lack of knowledge about the effectiveness of drugs has the lowest effect on choosing the medication. Also, the price and confidence in branded drugs showed a statistically significant impact on selecting the medicines. It was concluded that generic medication seems to be the best option for patients. Still, progressive alteration is required in people’s mentality to accept this fact, which may achieve by healthcare consumer education toward generic medication. In addition to this, the guidance of the healthcare system is essential for patients to switch to generic drugs from branded products.

PROSPECTS OF THE STUDY

The growth of the generic drug market depends on patients’ understanding of their safety and efficacy. Thus, understanding various factors that affect people’s behaviors toward generic drugs versus originator drugs will play an impotent role for many generic drug manufacturing companies. It will help them plan their policies for entering the market, combined with strategies to supply the generic drugs with the lowest prices. In addition to this, the guidance of physicians and raising medical awareness in the general public are required to increase patient and healthcare system confidence in the capability of generic medicines in fighting chronic diseases.

LIMITATIONS OF THE STUDY

A significant limitation of this study is the generalizability of the results since the sample included only respondents in Amman. Data showed that our surveyed population had a higher educational background than was initially hypothesized. Almost 80% of the participants reported having a college degree or higher (BCs degree 55.2%, MSc degree 6.7%, and PhD 1.8%). The lack of generalizability to the target population may bias the direction of our findings. Another limitation in our analyses was that our 50-question survey might have been too long for participants. However, the lack of definitions, examples, and images of both generic and branded- drugs in our survey may have led to misinterpretation by the respondents. Thus, responses may have varied based on which drug category the respondent believed he or she was addressing.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

All authors made substantial contributions to conception and design, acquisition of data, or analysis and interpretation of data; took part in drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content; agreed to submit to the current journal; and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

FUNDING

The authors have not received any funding support from the government and industry.

REFERENCES

Aburjai T, Yousif RO, AlSamydai MJ, Al-Samydai A, Al-Mamoori F, Azzam H. Protein supplements between consumer’s opinion and quality control: an applied study in Jordan. Int J Res Pharm Sci, 2019; 10(3):1961–9. CrossRef

Ahmed RR, Streimikiene D, Abrhám J, Streimikis J, Vveinhardt J. Social and behavioral theories and physician’s prescription behavior. Sustainability, 2020; 12(8):3379. CrossRef

Alhabeeb MJ. On consumer trust and product loyalty. Int J Consum Stud, 2007; 31(6):609–12. CrossRef

Al-Samydai M, Al-Kholaifeh A, Al-Samydai A. The impact of social media in improving patient’s mental image towards healthcare provided by private hospitals’ in Amman/Jordan. Indian J Public Health Res Dev, 2019; 10(2):491–6. CrossRef

Al-Samydai MJ, Qrimea IA, Yousif RO, Al-Samydai A, Aldin MK. The impact of social media on consumers’ health behavior towards choosing herbal cosmetics. J Crit Rev, 2020; 7(9):1171–6.

Aronsson T, Bergman MA, Rudholm N. The impact of generic drug competition on brand name market shares–evidence from micro data. Rev Ind Organ, 2001; 19(4):423–33. CrossRef

Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. 2nd edition, Academic Press, Cambridge, MA, 1999.

Davari M, Khorasani E, Tigabu BM. Factors influencing prescribing decisions of physicians: a review. Ethiop J Health Sci, 2018; 28(6):795–804. CrossRef

Desai RJ, Sarpatwari A, Dejene S, Khan NF, Lii J, Rogers JR, Dutcher SK, Raofi S, Bohn J, Connolly JG, Fischer MA. Comparative effectiveness of generic and brand-name medication use: a database study of US health insurance claims. PLoS Med, 2019; 16(3):e1002763. CrossRef

Dunne S, Shannon B, Dunne C, Cullen W. A review of the differences and similarities between generic drugs and their originator counterparts, including economic benefits associated with usage of generic medicines, using Ireland as a case study. BMC Pharmacol Toxicol, 2013; 14(1):1–19. CrossRef

Gallelli L, Palleria C, De Vuono A, Mumoli L, Vasapollo P, Piro B, Russo E. Safety and efficacy of generic drugs with respect to brand formulation. J Pharm Pharmacol, 2013; 4(Suppl1):S110. CrossRef

Guttier MC, Silveira MP, Luiza VL, Bertoldi AD. Factors influencing the preference for purchasing generic drugs in a Southern Brazilian city. Rev Saude Publ, 2017; 26:51–9. CrossRef

Haas JS, Phillips KA, Gerstenberger EP, Seger AC. Potential savings from substituting generic drugs for brand-name drugs: medical expenditure panel survey, 1997–2000. Ann Intern Med, 2005; 142(11):891–7. CrossRef

Håkonsen H, Toverud EL. Generic Drug Policies. Encyclopedia of Pharmacy Practice and Clinical Pharmacy, 2019; 130-138.

Ibrahim MI, Awaisu A. Generic medicines and biosimilars: impact on global pharmaceutical policy. In: Babar Z (ed.). Global pharmaceutical policy. Palgrave Macmillan, Singapore, Singapore, pp. 53–72, 2020. CrossRef

Johnston A, Stafylas P, Stergiou GS. Effectiveness, safety and cost of drug substitution in hypertension. Br J Clin Pharmacol, 2010; 70(3):320–34. CrossRef

Keenum AJ, DeVoe JE, Chisolm DJ, Wallace LS. Generic medications for you, but brand-name medications for me. Res Social Adm Pharm, 2012; 8(6):574–8. CrossRef

Kesselheim AS, Gagne JJ, Franklin JM, Eddings W, Fulchino LA, Avorn J, Campbell EG. Variations in patients’ perceptions and use of generic drugs: results of a national survey. J Gen Intern Med, 2016; 31(6):609–14. CrossRef

Kesselheim AS, Misono AS, Lee JL, Stedman MR, Brookhart MA, Choudhry NK, Shrank WH. Clinical equivalence of generic and brand-name drugs used in cardiovascular disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA, 2008; 300(21):2514–26. CrossRef

Kohli E, Buller A. Factors influencing consumer purchasing patterns of generic versus brand name over-the-counter drugs. South Med J, 2013; 106(2):155–60. CrossRef

Mohammadshahi M, Alipouri Sakha M, Zarei L, Karimi M, Peiravian F. Factors affecting medicine-induced demand and preventive strategies: a scoping review. Shiraz E-Medical J, 2019; 20(10):e87079. CrossRef

Nardi EP, Ferraz MB. Percepção de valor de medicamentos genéricos em São Paulo, Brasil. Cadernos de Saúde Pública, 2016; 32(2): e00038715. CrossRef

Olsson E, Sporrong SK. Pharmacists’ experiences and attitudes regarding generic drugs and generic substitution: two sides of the coin. Int J Pharm Pract, 2012; 20(6):377–83. CrossRef

Quintal C, Mendes P. Underuse of generic medicines in Portugal: an empirical study on the perceptions and attitudes of patients and pharmacists. Health policy, 2012; 104(1):61–8. CrossRef

Rizzo JA, Zeckhauser R. Generic script share and the price of brand-name drugs: the role of consumer choice. Int J Health Care Finance Econ, 2009; 9(3):291–316. CrossRef

Schumock GT, Walton SM, Park HY, Nutescu EA, Blackburn JC, Finley JM, Lewis RK. Factors that influence prescribing decisions. Ann Pharmacother, 2004; 38(4):557–62. CrossRef

Shamim-ul-Haq S, Ahmed RR, Ahmad N, Khoso I, Parmar V. Factors influencing prescription behavior of physicians. Pharm Innov J, 2014; 3(5):30–5.

Tian Y, Reichardt B, Dunkler D, Hronsky M, Winkelmayer WC, Bucsics A, Strohmaier S, Heinze G. Comparative effectiveness of branded vs. generic versions of antihypertensive, lipid-lowering and hypoglycemic substances: a population-wide cohort study. Sci Rep, 2020; 10(1):1–12. CrossRef

US Food and Drug Administration. Guidance for industry. Bioequivalence studies with pharmacokinetic endpoints for drugs submitted under an ANDA. US Food and Drug Administration, Silver Spring, MD, 2013. Available via http://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/GuidanceComplianceRegulatory-Information/Guidanees/UCM377465.pdf

Vogler S. How large are the differences between originator and generic prices? Analysis of five molecules in 16 European countries. Farmeconomia, 2012; 13(3S):29–41. CrossRef

Yousif RO, Al-samydai MJ. Factors influencing woman behavior to visit dental clinic to improve their smile. Indian J Public Health Res Dev, 2019; 10(2). CrossRef

APPENDIX

| Table 1. The questionnaire used in this study. [Click here to view] |