INTRODUCTION

The prevalence of breast cancer (BCa) during the period of 2007–2011 in Malaysia was 17.7% (Azizah et al., 2016). Patients with hormone receptor (HR)-positive BCa can benefit from endocrine therapy (ET). After the initiation of ET in HR-positive BCa patients, they should be evaluated for possible disease progression. Tumor response (TR) can be assessed using the Revised Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors guideline (Eisenhauer et al., 2009). TR can be categorized as (1) complete response; (2) partial response; (3) stable disease; and (4) progressive disease. Although ET has shown benefits in patients with HR-positive BCa, and its use has been associated with reduced mortality and BCa recurrence, previous trials have shown that some proportions of patients prescribed with ET still developed a progressive disease (Smith and Dowsett, 2003).

Little is known about the factors associated with a progressive disease in HR-positive BCa patients treated with ET. Thus, the purpose of the present study was to retrospectively follow-up a sample of HR-positive BCa patients treated with ET at Hospital Sultanah Nur Zahirah (HSNZ), a public hospital in the state of Terengganu, Malaysia. Patients were followed-up for 5 years to investigate the occurrence of disease progression 1 year after ET initiation. Additionally, the association of disease progression with (1) patients’ socio-demographic and clinical characteristics at baseline; (2) first year of ET medication possession ratio (MPR); and (3) use of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) was investigated. The study also intended to investigate the MPR of ET in the first, third, and fifth year of ET.

METHODS

Study Design

This was a retrospective study involving a sample of HR-positive BCa patients treated with ET in HSNZ. Data were collected from May to July 2019.

Ethical Approval

The study received ethical approval from the Medical Review and Ethics Committee of the Ministry of Health Malaysia (NMRR-19-832-47853) and Research and Ethics Committee of Universiti Teknologi MARA (600-IRMI [5/1/6]).

Study Population

The Terengganu Cancer Registry (TCR) was screened to identify BCa patients. Female patients, aged ≥18 years with a confirmed diagnosis of HR-positive BCa and who were prescribed with at least one type of ET were included in the study. Patients who were started with ET between January 2011 and June 2014 were selected to allow a 5-year follow-up of the patients during the data collection period. Patients with HR-positive BCa listed in the TCR but not receiving medical follow-ups in HSNZ were excluded. Patients who developed a progressive disease within the first year of diagnosis were also excluded.

Study Procedure

Eligible patients were retrospectively followed-up for 5 years from the date they started ET. The electronic medical record (EMR) of patients was accessed from the Hospital Information System (HIS). Relevant patients’ data were recorded using a standardized data collection form. Each EMR contains a patient’s demographic information, physicians’ clinical notes, laboratory investigations, results of imaging studies, history of radiotherapy and chemotherapy, and a list of prescribed medications. Details for each prescribed medication, including ET such as the dose, frequency, days supplied, and date of fill, can be obtained from the HIS. The date of the first ET prescription was used as the date of treatment initiation.

In the present study, patients’ adherence to ET was measured using MPR, i.e., the proportion of days that patients had medication available over the observation period (days covered). The MPR was calculated at three time points: at the end of the first, third, and fifth year of ET. Patients with an MPR value of ≥0.80 were considered as adherents to ET (Osterberg and Blaschke, 2005). Progressive disease is defined as at least a 20% increment in the sum of diameters of target lesions, an absolute increase of at least 5 mm in the sum, or the appearance of ≥1 new lesion(s) (Eisenhauer et al., 2009). CAM is defined as any medical and healthcare systems, practices, and products that are not normally considered as part of the conventional medicine (Wahab et al., 2014).

Data Analysis

All statistical analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS ver. 23. Continuous data were presented as mean and standard deviation (SD), whereas categorical data were presented as frequency and percentage. The percentage of categorical variables was compared using the chi-squared test or Fisher’s exact test, and continuous data were compared using the independent samples t-test. Statistical significance was established if p value was <0.05.

RESULTS

During the period between January 2011 and June 2014, 2263 cancer patients were identified from the TCR. Of all cancer patients identified, 16.1% (n = 365) were BCa patients. Out of the 365 BCa patients, 262 did not meet the inclusion criteria, resulting in 103 BCa patients for analysis.

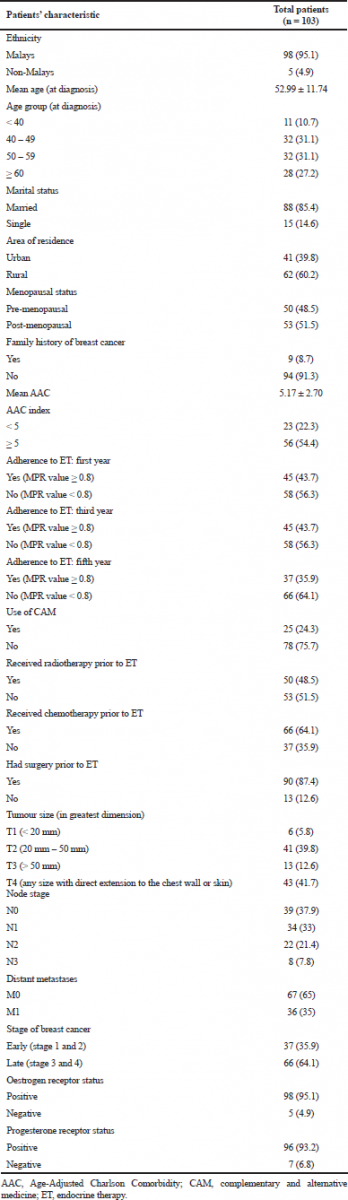

Table 1 shows the socio-demographic and clinical characteristics of the 103 eligible HR-positive BCa patients. Overall, most patients were Malays (n = 98, 95.1%), married (n = 88, 85.4%), and living in the rural areas (n = 62, 60.2%). The mean (± SD) age during BCa diagnosis was 52.99 (± 11.74) years. Slightly more than half of the patients were postmenopausal women (n = 53, 51.5%). Only a minority of them had a family history of BCa (n = 9, 8.7%). A history of CAM use was noted in 24.3% of patients (n = 25). Mean MPR values (± SD) for the first, third, and fifth year of ET were 0.70 ± 0.26, 0.66 ± 0.29, and 0.60 ± 0.32, respectively (not shown in the table). During the first year of ET, slightly more than half of the patients (n = 58, 56.3%) were considered as nonadherent to therapy as they had an MPR value of <0.80.

Most patients (n = 66, 64.1%) had late-stage cancer (stages 3 and 4) at diagnosis. About 42% of the patients (n = 43) had a large tumor (T4) at diagnosis and another 39.8% of patients (n = 41) had a tumor size of 20–50 mm (T2). Additionally, 62.1% of patients (n = 64) had a regional lymph node involvement (N1–N3). No distant cancer spread was found in 65% (n = 67) of patients.

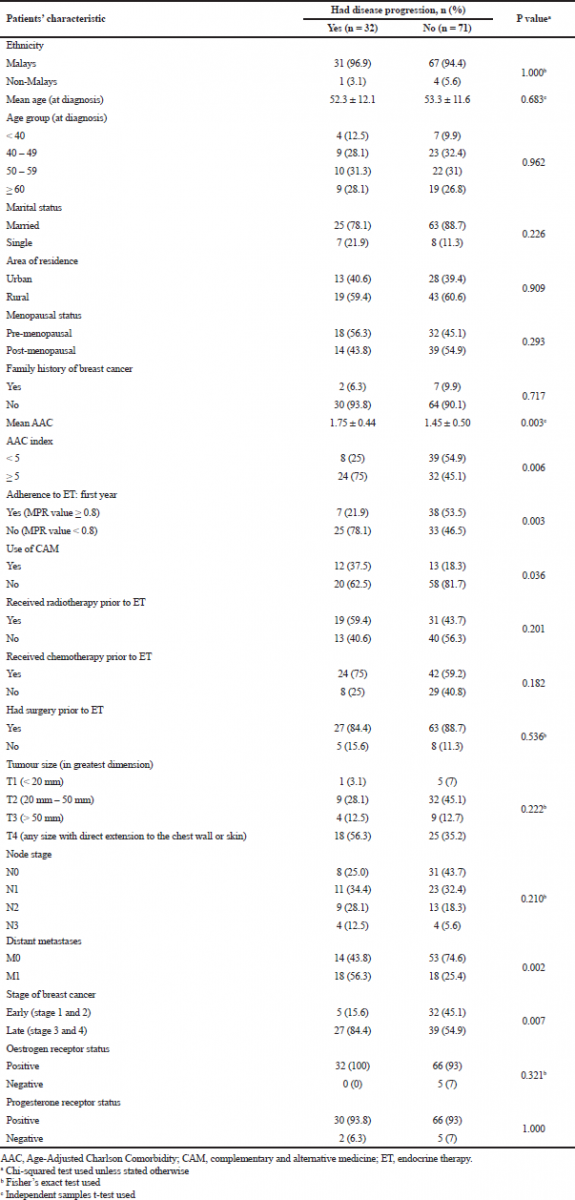

Overall, 31.1% of patients (n = 32) had progressive disease after 1 year of ET (Table 2). The mean (± SD) time to disease progression was 31.7 ± 15.3 months after ET initiation (range: 13–58 months). Progressive disease was associated with age-adjusted Charlson comorbidity (AAC) index of ≥5 (p = 0.006), patients who were nonadherent to ET (MPR < 0.80) during the first year of therapy (p = 0.003), a history of CAM use (p = 0.036), presence of distant metastases at diagnosis (p = 0.002), and late-stage BCa (p = 0.007).

DISCUSSION

The prevalence of BCa for the period of January 2011 and June 2014 in TCR was 16.1%. This prevalence was higher than that reported by the Malaysian National Cancer Registry Report in the period of January 2007–December 2011 for the state of Terengganu at 14.7% (534/3645) (Azizah et al., 2016). Although the period of patient inclusion for analysis in the present study was shorter than that in the previous report (3.5 years vs. 5 years), our finding suggests that BCa cases may have increased in the recent years.

In the present study, about one-third of HR-positive BCa patients who were treated with ET (n = 32, 31.1%) developed progressive disease after 1 year of ET initiation. Patients who were nonadherent to therapy in the first year of ET (defined as those with an MPR value of <0.80) were significantly associated with the occurrence of a progressive disease. Observation of the mean MPR value at the first, third, and fifth year of ET showed that adherence to ET among patients was the lowest in the fifth year (mean MPR value = 0.60). A declining trend of MPR over time for ET has been reported in previous studies (Partridge et al., 2008). This should be a cause for concern since nonadherence to ET is associated with poor clinical outcomes, e.g., disease recurrence and mortality (Gao et al., 2018; McCowan et al., 2008).

| Table 1. Socio-demographic and clinical characteristics of BCa patients. [Click here to view] |

A recent systematic review shows that patients’ nonadherence to ET was mainly attributed to the experience of side effects (Milata et al., 2018). However, it has been reported that patients’ nonadherence to ET can also be due to doubts about efficacy and concern about adverse effects (Gao et al., 2018). Therefore, in order to enhance patients’ adherence to ET, healthcare providers must ensure that patients have a good understanding about ET during initiation. Patients should be well informed about their disease and the importance of completing their prescribed ET. Moreover, patients should be made aware of the side effects of ET and should be encouraged to consult the physicians or pharmacists if they are experiencing ET side effects. Additionally, physicians and pharmacists should assist patients in managing ET side effects. For example, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs or other analgesics (e.g., acetaminophen and tramadol) can be prescribed to patients with arthralgia or other musculoskeletal symptoms (Dent et al., 2011). Pharmacists may reinforce patients’ adherence to ET through reminders during medicine refills and the use of adherence aids.

The majority of patients had late-stage cancer at diagnosis and about one-third of them had distant metastases. Our findings suggest that many patients may have delayed seeking medical care for BCa and therefore received delayed treatment. This is worrisome since survival for BCa is reduced with delayed treatment (Smith et al., 2013). In fact, our results showed that patients who had late-stage cancer and had distant metastases at diagnosis were more likely to be associated with a progressive disease. Therefore additional efforts must be made to promote BCa screening behaviors among women through campaigns or educational programs. Additionally, there is a need to educate the public about the symptoms of BCa and to highlight the importance of early diagnosis and early treatment (Caplan, 2014; Brinton et al., 2017).

About a quarter of patients in the present study were reported using CAM at diagnosis. Although it is unknown whether patients continued using CAM throughout ET, there was a significant association with the history of CAM use at diagnosis with the occurrence of a progressive disease. Previous studies have shown that many patients had the belief that CAM are more useful than modern medicine and were willing to try CAM before seeking conventional treatment (Taib et al., 2007; Wahab et al., 2017; Norsa’adah et al., 2012). BCa patients who experimented with CAM would finally seek conventional medical care if their disease worsened (Taib et al., 2007). These patients who presented with late-stage cancers would have poorer chances for survival (Caplan, 2014). Additionally, although patients may integrate the use of CAM with conventional treatment, there is a concern about patients discontinuing ET in favor of CAM. Thus, healthcare providers should be vigilant of CAM use in BCa patients and routinely monitor patients’ adherence to ET.

| Table 2. Association of socio-demographic and clinical characteristics of BCa patients with disease progression. [Click here to view] |

Our results also showed that patients with an AAC index of ≥5 were significantly associated with a disease progression. In a study in Denmark, there was a trend of higher mortality among BCa patients with comorbidities after adjusting for age and stage (Cronin-Fenton et al., 2007). Similarly, in a study in the United States, BCa patients who had acute or chronic renal failure, liver disease, and cerebrovascular disease were shown to have a higher risk of mortality (Yancik et al., 2001). BCa patients who have multiple comorbidities may receive less aggressive therapy (Louwman et al., 2005) In fact, further analysis of our data showed that BCa patients who had an AAC index of ≥5 were less likely to undergo surgery. Further studies should be warranted to investigate the impacts of comorbidity on treatment choice and its effect on prognosis among Malaysian BCa patients.

The present study has several limitations. Our study is a retrospective study of a sample of heterogeneous BCa patients who were exposed to a variety of ET. Additionally, the measurement of adherence through the calculation of MPR may have limitations. There is a possibility that this method may overestimate patients’ adherence to ET. It is possible that patients may refill medications as scheduled but not adhering to the regimen. The small sample size of patients in the study limits the generalization of study findings and impedes the use of multivariate statistical analysis. A large multicenter study should be warranted in the future.

CONCLUSION

The occurrence of a progressive disease was associated with patients who had an AAC index of ≥5, MPR <0.80 during the first year of ET, a history of CAM use, and presence of distant metastases and late-stage cancer at diagnosis. There was a decreasing trend of adherence to ET among the patients. Therefore, the need to reinforce adherence to ET in BCa patients is crucial. Moreover, healthcare providers, such as pharmacists and physicians, should be vigilant about CAM use in BCa patients. Since many patients were diagnosed with late-stage cancer, there is a pressing need to educate the public about BCa and to encourage women to seek early treatment if symptoms are present.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to thank the Director-General of Health Malaysia for permission to publish this article.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

All authors have no conflicts of interest.

FUNDING

This study is not funded by any organization.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

All authors made substantial contributions to conception and design, acquisition of data, or analysis and interpretation of data; took part in drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content; agreed to submit to the current journal; gave final approval of the version to be published; and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

REFERENCES

Azizah AM, Nor Saleha I, Noor Hashimah A, Asmah Z, Mastulu W. Malaysian national cancer registry report 2007–2011. Malaysia cancer statistics, data and figure. Putrajaya, Malaysia: National Cancer Institute, Ministry of Health, 2016.

Brinton L, Figueroa J, Adjei E, Ansong D, Biritwum R, Edusei L, Nyarko KM, Wiafe S, Yarney J, Addai BW. Factors contributing to delays in diagnosis of breast cancers in Ghana, West Africa. Breast Cancer Res Treat, 2017; 162(1):105–14. CrossRef

Caplan, L. Delay in breast cancer: implications for stage at diagnosis and survival. Front Public Health, 2014; 2:87. CrossRef

Cronin-Fenton D, Nørgaard M, Jacobsen J, Garne JP, Ewertz M, Lash T, Sørensen HT. Comorbidity and survival of Danish breast cancer patients from 1995 to 2005. Br J Cancer, 2007; 96(9):1462–68. CrossRef

Dent SF, Gaspo R, Kissner M, Pritchard KI. Aromatase inhibitor therapy: toxicities and management strategies in the treatment of postmenopausal women with hormone-sensitive early breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat, 2011; 126(2):295–310. CrossRef

Eisenhauer EA, Therasse P, Bogaerts J, Schwartz LH, Sargent D, Ford R, Dancey J, Arbuck S, Gwyther S, Mooney M. New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1). Eur J Cancer, 2009; 45(2):228–47. CrossRef

Gao P, You L, Wu D, Shi A, Miao Q, Rana U, Martin DP, Du Y, Zhao G, Han B, Zheng C, Fan Z. Adherence to endocrine therapy among Chinese patients with breast cancer: current status and recommendations for improvement. Patient Prefer Adherence, 2018; 12:887–97. CrossRef

Louwman W, Janssen-Heijnen M, Houterman S, Voogd A, Van Der Sangen M, Nieuwenhuijzen, G, Coebergh J. Less extensive treatment and inferior prognosis for breast cancer patient with comorbidity: a population-based study. Eur J Cancer, 2005; 41(5):779–85. CrossRef

McCowan C, Shearer J, Donnan P, Dewar J, Crilly M, Thompson A, Fahey T. Cohort study examining tamoxifen adherence and its relationship to mortality in women with breast cancer. Br J Cancer, 2008; 99(11):1763–68. CrossRef

Milata JL, Otte JL, Carpenter JS. Oral endocrine therapy nonadherence, adverse effects, decisional support, and decisional needs in women with breast cancer. Cancer Nurs, 2018; 41(1):E9–18. CrossRef

Norsa’adah B, Rahmah MA, Rampal KG, Knight A. Understanding barriers to Malaysian women with breast cancer seeking help. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev, 2012; 13(8):3723–30. CrossRef

Osterberg L, Blaschke T. Adherence to medication. N Engl J Med, 2005; 353:487–97. CrossRef

Partridge AH, LaFountain A, Mayer E, Taylor BS, Winer E, Asnis-Alibozek A. Adherence to initial adjuvant anastrozole therapy among women with early-stage breast cancer. J Clin Oncol, 2008; 26(4):556–62. CrossRef

Smith EC, Ziogas A, Anton-Culver, H. Delay in surgical treatment and survival after breast cancer diagnosis in young women by race/ethnicity. JAMA Surg, 2013; 148(6):516–23. CrossRef

Smith IE, Dowsett M. Aromatase inhibitors in breast cancer. N Engl J Med, 2003; 348(24):2431–42. CrossRef

Taib NA, Yip CH, Ibrahim M, Ng C, Farizah H. Breast cancer in Malaysia: are our women getting the right message? 10 year-experience in a single institution in Malaysia. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev, 2007; 8(1):141–5.

Wahab MSA, Ali AA, Zulkifly HH, Aziz NA. The need for evidence-based complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) information in Malaysian pharmacy curricula based on pharmacy students’ attitudes and perceptions towards CAM. Curr Pharm Teach Learn, 2014; 6(1):114–21. CrossRef

Wahab MSA, Othman N, Othman NHI, Jamari AA, Ali AA. Exploring the use of and perceptions about honey as complementary and alternative medicine among the general public in the state of Selangor, Malaysia. J Appl Pharm Sci, 2017; 7(12):144–50.

Yancik R, Wesley MN, Ries LA, Havlik RJ, Edwards BK, Yates JW. Effect of age and comorbidity in postmenopausal breast cancer patients aged 55 years and older. J Am Med Assoc, 2001; 285(7):885–92. CrossRef