INTRODUCTION

Sponges are a known source of natural products, several of which have pharmacological functions (Gandelman et al., 2014). In the last decade, ≥2,400 novel compounds have been isolated from ≥600 species of sponges. These compounds were classified as peptides, terpenoids, terpenes, and alkaloids (Mehbub et al., 2014). Interestingly, many of them were reported to be synthesized by sponge-associated bacteria, which are supposed to play an important role in the host defense against environmental stress, including pathogens, parasites, and parasitoids (Flórez et al., 2015). Thus, marine bacteria are expected to be a promising source for the sustainable production of new particular targeted sponge-derived bioactive compounds without causing significant damage to the environment.

The bioactive compounds produced by bacteria, such as nonribosomal peptides, may act as antibiotics (Martínez?Núñez and López, 2016), immunosuppressants (Gao et al., 2012), or antitumor agents (Sato et al., 2013). These compounds are synthesized by multidomain enzymes, namely, nonribosomal peptide synthetase (NRPS). The core catalytic domains of NRPS comprise a thiolation (T), adenylation (A), and condensation (C) domain and usually terminate with a thioesterase (Te) domain (Miller and Gulick, 2016). Molecular detection using primers complementing with the conserved A-domain sequence has been commonly used to discover new NRPS genes in marine bacteria (Tambadou et al., 2014). This conserved domain provides molecular targets for the identification of bioactive compounds from bacteria. By employing this method, the diversity of NRPS genes in microorganisms, such as fungi (Boettger and Hertweck, 2013), bacteria (Su et al., 2014), and actinomycetes (Ziemert et al., 2014), has been reported.

The Indonesian seas could be endowed with diverse compounds that might be a great source of components for medicinal use. However, until 2017, 732 marine natural products have been identified. Sponge was found as a major source of these compounds (68%). In contrast, only 0.3% of compounds are originated from bacteria, especially the actinobacteria group (Hanif et al., 2019). Therefore, exploration of Indonesian marine bacteria-derived compounds is necessary, both through molecular approaches and in vitro studies. Although approximately 70% of Indonesian territory is the sea, investigations of NRPS genes in marine bacteria from this area are rare. Hence, we focused on the anticancer activity and biodiversity analysis of the sponge-associated bacteria in the Indonesian seas. We used polymerase chain reaction (PCR) screening with primers targeting the conserved A-domain of NRPS genes to identify nine bacteria associated with sponges that were collected from the Raja Ampat Island in Papua and Kepulauan Seribu in Jakarta. Based on subsequent 16S-rRNA-based identification and enterobacterial repetitive intergenic consensus (ERIC)-PCR analysis, the identified bacterial isolates belonged to the Gammaproteobacteria class. We also investigated the anticancer properties of bioactive compounds that were identified from extracts of the isolated bacteria.

| Table 1. Genetic materials used in this study. [Click here to view] |

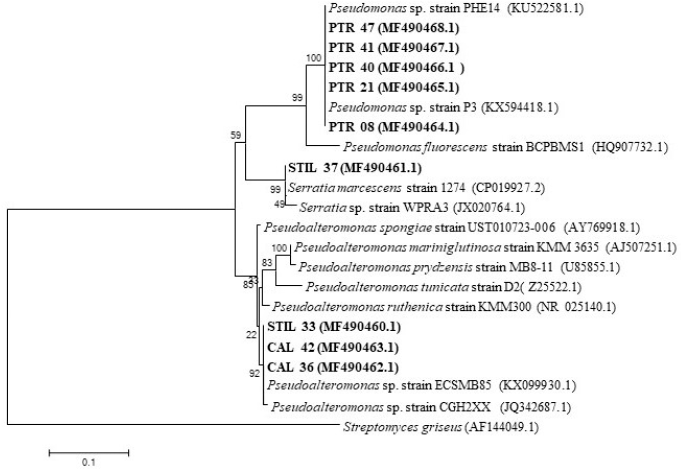

| Figure 1. Phylogenetic tree of A-domain of NRPS genes from nine bacterial isolates to the reference strains in amino acid level. Numbers at the nodes denote the levels of bootstrap support in 1,000 time repetitions. [Click here to view] |

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial isolates and mammalian cells

The nine bacterial isolates used in this study were isolated in the previous study (Tokasaya, 2010). Genetic material sources are shown in Table 1. MCF-7 (human breast adenocarcinoma cells), A549 (human lung adenocarcinoma cells), WiDr (human colon adenocarcinoma cells), and MCF-12A (human mammary epithelial cells) were obtained from Primate Research Center, IPB University.

| Table 2. A-domain of NRPS genes from sponge-associated bacteria compared with those in the GenBank database, which were obtained using BlastX. [Click here to view] |

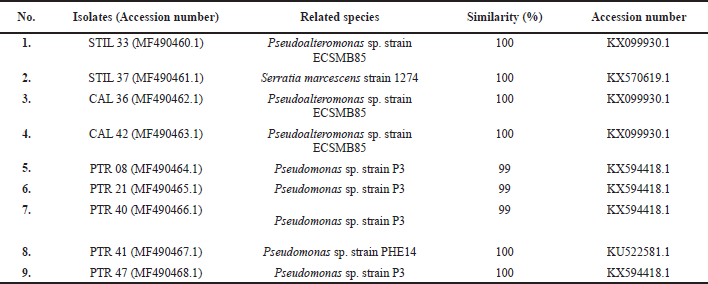

| Figure 2. Genetic relationship of nine bacteria isolated from sponge compared to their relative strain according to the 16S-rRNA gene. [Click here to view] |

Genomic DNA extraction, NRPS genes screening, and phylogenetic analysis

Genomic DNA from bacterial cultures was isolated using a PrestoTM Mini gDNA Bacteria Kit (Geneaid) following the protocol’s guidelines. Then, the A-domain of NRPS genes from the bacterial isolates was amplified using PCR with primers for A-domain (forward: 5? AAR DSI GGI GSI GSI TAY BIC C-3? and reverse: 5?-CKR WAI CCI CKI AIY TTI AYY TG-3?) (Schirmer et al., 2005). The 50 μl PCR mix consisted of 5 μl of 10 pmol forward primers, 5 μl of 10 pmol reverse primers, 25 μl GoTaq Green® Master Mix 123 (Promega), 4 μl of DNA template (100 ng/μl), and 11 μl of nuclease-free water. The PCR cycling conditions and phylogenetic tree construction were as described by Wahyudi et al. (2018).

| Table 3. Bacterial identity based on 16S-rRNA gene sequence. [Click here to view] |

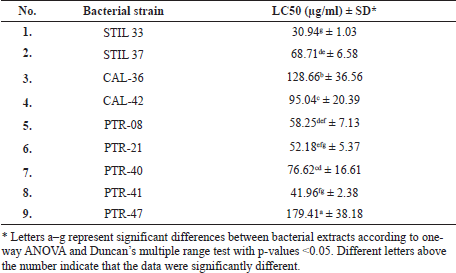

| Table 4. Toxicity of bacterial extracts on A. salina. [Click here to view] |

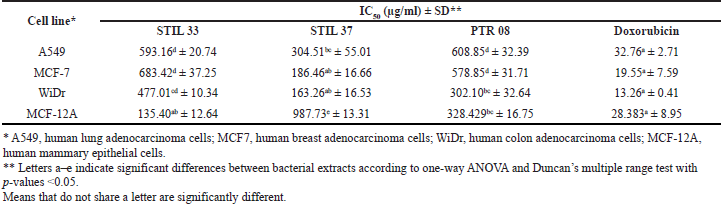

| Table 5. Median IC50 value of bacterial extracts and doxorubicin against cancer and normal cell lines. [Click here to view] |

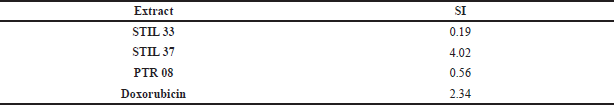

| Table 6. The SI of bacterial extracts and doxorubicin treatment. [Click here to view] |

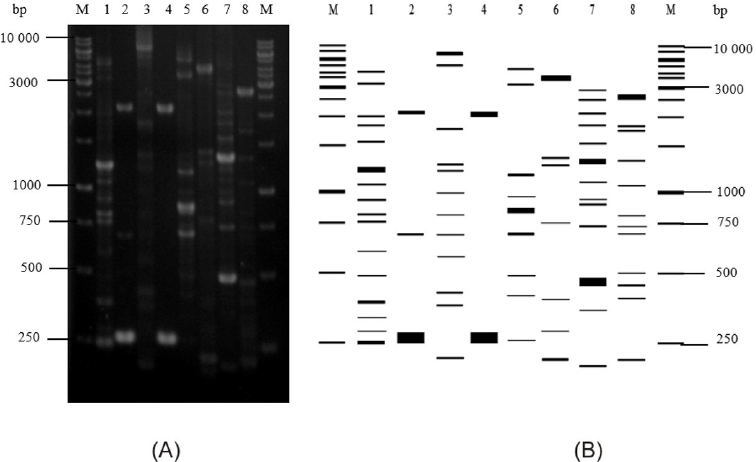

| Figure 3. ERIC-PCR profiles of marine sponge-associated bacteria. (A) ERIC-PCR profiles in 1.5% agarose. (B) Illustration of ERIC-PCR profiles created by using Ms. Excel (Microsoft) and Gel Analyzer Software. M, molecular marker; lane 1, STIL 33; lane 2, CAL 42; lane 3, CAL 36; lane 4, PTR 08; lane 5, PTR 21; lane 6, PTR 40; lane 7, PTR 47; lane 8, STIL 37. [Click here to view] |

PCR amplification of 16S-rRNA genes and phylogenetic tree construction

The 16S-rRNA genes were amplified using primers 63f (5?-CAG GCC TAA CAC ATG CAA GTC-3?) and 1387r (5?-GGG CGG WGT GTA CAA GGC-3?) that were developed by Marchesi et al. (1998) to target a conserved region of approximately 1,300 bp. The PCR mixture, cycling conditions, and phylogenetic tree construction were carried out as per Wahyudi et al. (2018).

Genetic profiling by ERIC-PCR

Bacterial isolates that had the same 16S-rRNA identity were then identified by ERIC-PCR methods to investigate the intraspecies diversity. The 25 μl PCR mix consisted of 1 μl of 25 pmol ERIC1R primers (5?-ATG TAA GCT CCT GGG GAT TCA C-3?), 1 μl of 25 pmol ERIC2F primers (5?-AAG TAA GTG ACT GGG GTG AGC G-3?) (Versalovic et al., 1991), 1 μl of DNA template (100 ng/μl), 12.5 μl GoTaq Green® Master Mix 123 (Promega), and 9.5 μl of nuclease-free water, which were used for amplification. The PCR conditions were as per Ayu et al. (2014).

Culture and extraction of bacterial metabolites

Nine bacterial isolates were inoculated into 1 l of each seawater complete (SWC) medium containing 3 ml glycerol, 1 g yeast extract, 5 g peptone, 250 ml distilled water, and 750 ml seawater. The bacterial cultures were incubated for 72 hours at 28°C with agitation at 120 rpm. Then, the bioactive compounds were extracted by adding the 1 l of bacterial culture to 1 l of ethyl acetate and shaking the mixture for 15 minutes in a separating funnel. The ethyl acetate layer was evaporated at 45°C using a rotary evaporator, and the metabolite extract was diluted in dimethyl sulfoxide.

Toxicity assay of bacterial metabolites

The toxicity effect of the bacterial extracts was assessed according to the brine shrimp lethality test (BSLT). Briefly, 20 Artemia salina larvae were grown in a vial, each containing 4 ml of seawater with different concentrations of bacterial extract (1,000, 750, 500, 250, 100, 10, and 0 μg/ml) and incubated at 27°C for 24 hours under a light. Thereafter, the surviving larvae were counted. Each sample was analyzed in triplicate. The mortality percentage of each treatment was determined using the following formula:

The lethal concentration (LC50) value was determined by converting the percentage of mortality to the probit value. The LC50 was observed from the fit line by linear regression analysis (Meyer et al., 1982).

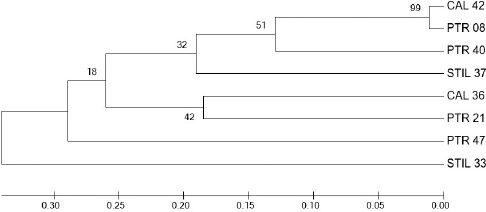

| Figure 4. Phylogenetic tree constructed by binary data of ERIC-PCR profiles of nine sponge-associated bacteria using the unweighted pair group method with arithmetic mean method in MEGA 7.0. [Click here to view] |

Anticancer analysis

The microculture tetrazolium test (MTT) was used for in vitro assessment of the cytotoxic properties of the bacterial extracts toward normal cells (human mammary epithelial cells, MCF-12A) and cancer cells (human breast adenocarcinoma cells, MCF7; human lung adenocarcinoma cells, A549; and human colon adenocarcinoma cells, WiDr). MCF-12A and A549 were seeded in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium, and MCF-7 and WiDr were cultured in Roswell Park Memorial Institute medium added with 10% fetal bovine serum and 100 μg/ml penicillin and streptomycin. Then, 50 μl of cell suspension (5 × 103 cells/well) was seeded into 96-well plates containing 50 μl of medium 173 with different extract concentrations (800, 400, 200, 100, 50, 25, and 0 μg/ml) and incubated at 35°C in 5% CO2 for 48 hours. All experiments were performed in triplicate, and doxorubicin was applied as a positive control. After incubation, the treated cells in each well were reacted with 10 μl of MTT in phosphate-buffered saline and incubated at 35°C for 4 hours. The formazan crystals formed were diluted in 100 μl of ethanol 96%. The absorbance was quantified via a microplate reader at 595 nm. The percentage of cancer cell proliferation inhibition was determined using the following formula:

We performed three replicates for each MTT assay. The median inhibition concentration (IC50) value was calculated by linear regression between the percentage of cell growth inhibition and the extract concentration curve.

Calculation of selectivity index (SI)

The SI of each bacterial extract against cancer and normal cells was calculated by comparing the IC50 value of MCF-7 cells and MCF-12A cells. An SI value ≥2 indicated selective toxicity against cancer cells only. Extracts with SI value <2 were considered toxic to both cancer and normal cells. The SI value was determined using the formula:

SI = IC50 value in normal cells/IC50 value in cancer cells

Gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS) analysis

The composition of chemical compounds in STIL 37 extract was identified with GC-MS (Pyrolysis 5973 GC-MS, Agilent Technology). 0.6 μl of extract solution was injected into a column with HP-5MS column type (30 m × 250 μm × 0.25 μm). The early oven temperature was 80°C and constantly increased at 15°C/minute until 300°C and detained for 20 minutes. Helium gas was used as a carrier at a 1 ml/min flow rate. The injection temperature was 300°C, and the aux temperature was continued at 300°C. The result was analyzed by the GC-MS Pyrolysis program (WILLEY9THN 08. L).

Statistical analysis

The data were presented as average ± standard deviation from three repetitions. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was applied to compare the average values with 95% and 99% confidence levels. Further analysis was determined using Duncan’s multiple range test, and p-values <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Diversity of NRPS genes in sponge-associated bacteria

Nine bacterial isolates were successfully identified as possessing NRPS genes by PCR technique using primers targeting the conserved A-domain and resulting in a band size of approximately 1,000 bp. Following a search of the National Center for Biotechnology Information’s GenBank database, it was determined that these isolates possessed distinctive NRPS genes relative to those in the GenBank database. Sequence with high similarity to NRPS genes (≥95%) was observed in 3/9 isolates, and the other six isolates showed a low similarity (<90%) to related genes in the GenBank database (Table 2). Based on the A-domain of NRPS genes, all isolates belonged to the class of Gammaproteobacteria and were from the Pseudoalteromonas, Pseudomonas, or Serratia genus (Fig. 1).

Bacterial identity based on 16S-rRNA and their intrastrain differentiation

We identified nine bacterial isolates with various NRPS genes based on 16S-rRNA PCR, which resulted in a PCR product of approximately 1,300 bp. All bacterial isolates were identified as Gammaproteobacteria and included the genera of Pseudomonas, Pseudoalteromonas, and Serratia (Table 3). Phylogenetic tree construction using the neighbor-joining tree method also showed relatively similar grouping with strains from the GenBank database (Fig. 2). Surprisingly, four isolates (PTR 40, PTR 47, PTR 08, and PTR 21) showed the same homology with Pseudomonas sp. strain P3, while three isolates (STIL 33, CAL 36, and CAL 42) were homologous with Pseudoalteromonas sp. strain ECSMB85.

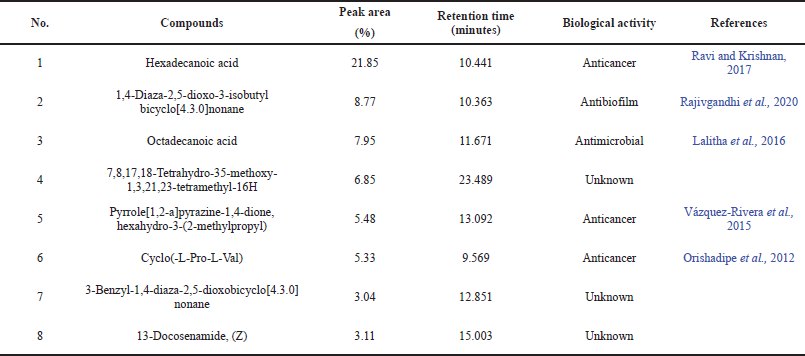

| Table 7. Eight major compounds in STILL-37 ethyl acetate extract identified by GC-MS. [Click here to view] |

Isolates with the same closest relative strain in the GenBank database were distinguished from each other by ERIC-PCR. Each strain showed unique ERIC patterns distinctive from each other, observed as multiple fragments of DNA amplicons that were 0.20–6.0 kb in length (Fig. 3). The genetic relationship-based ERIC patterns of Pseudomonas and Pseudoalteromonas strains are shown in Figure 4.

Toxicity of bacterial crude extracts

The toxicity of the bacterial crude extracts was determined according to the LC50 value, and the extracts were all found to be toxic in a dose-dependent manner, with the crude extracts showing a toxicity level of 30.94–179.41 μg/ml. The STIL 33 isolate demonstrated the highest toxicity level (30.94 μg/ml), followed by PTR 41 isolate (41.96 μg/ml), PTR 21 (52.18 μg/ml), and PTR 08 (58.25 μg/ml) (Table 4).

Anticancer activity of extracts derived from sponge-associated bacteria

The three potential extracts with the lowest LC50 values were used for anticancer analysis against three cancer cell lines (A549, MCF-7, and WiDr) and normal cells (MCF-12A). The cytotoxic effects of the extracts were determined according to the optical density values and morphological changes in the cells after 48 hours of treatment. The anticancer activity of the extracts was determined by their IC50 values. All three isolates tested (STIL 33, STIL 37, and PTR 08) exerted different anticancer activities (IC50, 135.40 to 987.73 μg/ml) compared with doxorubicin as a positive control (IC50, 13.26 to 32.76 μg/ml) (Table 5). The extract derived from STIL 37 demonstrated the best anticancer property, with an IC50 value of 163.26 μg/ml against human colon adenocarcinoma cells (WiDr). This extract also showed a high SI (4.02), two times higher than that of doxorubicin (2.34) (Table 6).

Major compounds found in STIL 37 extract

Eight major compounds were found in STIL 37 extract as identified by GC-MS analysis, such as hexadecanoic acid (1), 1,4-diaza-2,5-dioxo-3-isobutyl bicyclo[4.3.0]nonane (2), octadecanoic acid (3), 7,8,17,18-tetrahydro-35-methoxy-1,3,21,23-tetramethyl-16H (4), pyrrole[1,2-a]pyrazine-1,4-dione, hexahydro-3-(2-methylpropyl) (5), cyclo(-L-Pro-L-Val) (6), 3-benzyl-1,4-diaza-2,5-dioxobicyclo[4.3.0]nonane (7), and 13-docosenamide, (Z) (8). Table 7 shows the retention time, peak area (%), and biological activities of these compounds.

DISCUSSION

NRPS genes are promising targets for the identification of bacteria capable of producing bioactive metabolites. The discovery of various NRPS genes in bacteria could serve as molecular evidence of the ability of bacteria to produce bioactive compounds. In this study, we identified nine bacterial isolates with diverse NRPS genes that belonged to either the Pseudoalteromonas, Pseudomonas, or Serratia genus. Bacteria carrying these genes are potentially able to synthesize bioactive compounds with pharmacological properties. Gonzalez et al. (2016) detected NRPS genes in Pseudomonas aeruginosa that were capable of inhibiting quorum-sensing LasR-dependent signals. Pseudomonas sp. isolated from Red Sea sponge that was identified as having NRPS genes showed antioxidant activity and cytotoxicity against hepatocellular carcinoma cells (Moneam et al., 2017). In our investigation, six of the nine isolates showed a low similarity (<90%) to the related genes in the GenBank database, suggesting that the genes in these Indonesian sea sponge bacteria were novel. The existence of a variety of NRPS genes in marine bacteria indicates the presence of rich metabolite sources in the marine environment.

The identity of the nine bacteria with various NRPS genes was identified according to 16S-rRNA sequencing. This sequence is usually used as a genetic marker for bacterial identification. The 16S-rRNA genes are conserved in the genomes of all bacteria and suitable for molecular identification due to their small variability and their species specificity (Johnson et al., 2019). All nine bacterial isolates, which belonged to either the Pseudomonas, Pseudoalteromonas, or Serratia genus, showed high sequence similarity (≥99%) with their closest relatives in the GenBank database. The similarity is accepted to identify bacteria into the same species. Due to their potential to produce bioactive metabolites, these genera are of interest to the study, particularly in the microbial bioprospection field. The Pseudomonas genus is well known as a producer of at least 795 compounds (Isnansetyo and Kamei, 2009). Interestingly, four isolates (PTR 21, PTR 40, PTR 47, and PTR 08) were closely related to Pseudomonas sp. strain P3, which has the ability to degrade p-nitrophenol (Cui et al., 2002). The Pseudoalteromonas genus shows potential because of its ability to produce antimicrobial metabolites (Offret et al., 2016). Furthermore, Serratia marcescens strains produce prodigiosin, a red pigment that has been reported to have anticancer properties against prostate cancer and human choriocarcinoma cell lines (Li et al., 2018).

Although the 16S-rRNA gene is sufficient for bioinformatics purposes, its DNA sequence cannot be utilized to determine intrastrain differentiations. In our study, STIL 33, CAL 36, and CAL 42 were identified as Pseudoalteromonas sp. ECSMB85 and located in the same phylogenetic clade, while PTR 08, PTR 21, PTR 40, and PTR 47 were known as Pseudomonas sp. strain P3 and also located in the same clade, indicating that those bacteria were very closely related to each other based on their 16S-rRNA gene sequences. Therefore, another parameter is required to distinguish the isolates from each other. In this study, we used ERIC-PCR to differentiate between the genetic profiles of Pseudomonas and Pseudoalteromonas isolated from marine sponges. The ERIC-PCR approach is based on targeting a repeating and noncoding DNA consensus sequence in the intergenic region of the bacterial genome. This method has been used to type Gram-negative Pseudomonas (Han et al., 2014) and Pseudoalteromonas strains (Elena et al., 2002). Surprisingly, isolates identified as Pseudomonas sp. strain P3 (PTR 08, PTR 21, PTR 40, and PTR 47) and Pseudoalteromonas sp. strain ECSMB85 (STIL 33, CAL 36, and CAL 42) according to 16S-rRNA-based identification exhibited different ERIC patterns. Furthermore, it is noteworthy that all isolates used in this study were separated into different clades in the phylogenetic tree constructed from the ERIC patterns of each isolate, suggesting that these isolates might differ in strain taxa. These results indicate a high diversity among marine bacteria.

We used BSLT to screen for the toxicity of metabolites extract derived from nine sponge-associated bacteria endowed with NRPS genes. All extracts exhibited various toxicity levels. The LC50 values were <1,000 μg/ml, indicating that the extracts were biologically active. The differences in toxicity levels indicated that the extracts from the sponge-associated bacteria were chemically diverse. Of the nine extracts tested, the STIL 33-derived extract showed the best toxicity (LC50 = 30.94 μg/ml). Because our previous studies had reported that three isolates (STIL 33, STIL 37, and PTR 08) showed antioxidant properties (Prastya et al., 2020; Yoghiapiscessa et al., 2016), we selected extracts of these isolates for anticancer analysis against carcinoma and normal cells.

Evaluation of the anticancer activity of the three revealed varying levels of growth inhibition of both normal and cancer cells, as indicated by IC50 values. Thus, each extract likely exerted a specific anticancer activity toward each cancer cell line. The differences observed in their anticancer activity could be due to differences in the chemical composition of the extracts and the resistance of each cancer cell line. Of the three extracts tested, STIL 37 exhibited the best anticancer properties, with an IC50 value of 163.26 μg/ml against human colon adenocarcinoma cells (WiDr). Moreover, this extract also showed a high SI (4.02), two times higher than doxorubicin (2.34), suggesting that it likely had a selective action in inhibiting cancer cell proliferation. In this study, 16S-rRNA-based identification showed STIL 37 belonging to Serratia marcescens. In the earlier studies, prodigiosin, a red pigment produced by this species, has also been shown to significantly inhibit the proliferation of Hep2 cell lines, with an IC50 value of 31.25 μg/ml (Vijayalakshmi and Jagathy, 2016). Supporting these results, a STIL 37-derived extract was also found to have cytotoxic properties against some hematopoietic cancer cell lines (Priyanto et al., 2017). Therefore, it is crucial to investigate the bioactive compounds derived from STIL 37 for their potential for further exploitation for medicinal applications, mainly as an anticancer agent.

In this study, GC-MS analysis identified that STIL 37 extract was dominated by several biologically active compounds, including hexadecanoic acid, pyrrole[1,2-a]pyrazine-1,4-dione, hexahydro-3-(2-methylpropyl), and cyclo(-L-Pro-L-Val). Those compounds might contribute to the anticancer property of this extract. A previous study demonstrated that hexadecanoic acid extracted from Kigelia pinnata leaves shows cytotoxic activity against human colorectal carcinoma (HCT-116) cells (Ravi and Krishnan, 2017). Other compounds, pyrrole[1,2-a]pyrazine-1,4-dione, hexahydro-3-(2-methylpropyl), and cyclo(-L-Pro-L-Val), extracted from Streptomyces mangrovisoli sp. nov and Staphylococcus sp. strain MB30, respectively, also have been known to have anticancer activity toward A549 and HeLa cell lines (Lalitha et al., 2016; Vázquez-Rivera et al., 2015). Anticancer property of this extract also may be supported by other major compounds detected in this extract, such as 1,4-diaza-2,5-dioxo-3-isobutyl bicyclo[4.3.0]nonane, octadecanoic acid, 3-benzyl-1,4-diaza-2,5-dioxobicyclo[4.3.0]nonane, and 13-docosenamide, (Z). Those dominant compounds may induce apoptotic pathways leading to a decrease in viability of cancer cells.

CONCLUSION

Our present investigation concluded that molecular screening via NRPS gene amplification in bacteria could be an effective approach to identifying those capable of producing bioactive compounds. Nine bacterial isolates from three different genera (Pseudomonas, Pseudoalteromonas, and Serratia) were capable of producing biologically active compounds. Three isolates were shown to inhibit three carcinoma cell lines at different concentrations. The STIL 37-derived extract should be studied further using fractionation and structural elucidation. A high level of bioactivity and target cell selectivity is expected.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This study was partly supported by the Ministry of Research, Technology, and Higher Education of the Republic of Indonesia through University Excellence Basic Research (“Penelitian Unggulan Perguruan Tinggi”) 2016 (Contract No. 079/SP2H/LT/DRPM/II/2016) and partly supported by the Basic Research (“Penelitian Dasar”) from the Ministry of Research and Technology/National Research and Innovation Agency of the Republic of Indonesia (Contract No: 1/E1/KP.PTNBH/2021) to ATW. The authors acknowledge all the support.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

All authors declare there is no conflict of interest related to this study.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

All authors have contributed to the concept and experimental design, data acquisition, data analysis and interpretation, and paper writing.

ETHICAL APPROVALS

This study does not involve experiments on animals or human subjects.

DATA AVAILABILITY

All data generated and analyzed are included within this research article.

PUBLISHER’S NOTE

This journal remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published institutional affiliation.

REFERENCES

Ayu E, Suwanto A, Barus T. Klebsiella pneumoniae from Indonesian tempeh were genetically different from that of pathogenic isolates. Microbiol Indonesia, 2014; 8:9–15. CrossRef

Boettger D, Hertweck C. Molecular diversity sculpted by fungal PKS-NRPS hybrids. Chembiochem, 2013; 14(1):28–42. CrossRef

Cui Z, Zhang R, He J, Li S. Isolation and characterization of a p-nitrophenol degradation Pseudomonas sp. strain P3 and construction of a genetically engineered bacterium. Wei Sheng Wu Xue Ba, 2002; 42(1):19–26.

Elena P, Ivanova GR, Matte MH, Matte TC, Anwarul H, Rita RC. Characterization of Pseudoalteromonas citrea and P. Nigrifaciens isolated from different ecological habitats based on REP-PCR genomic fingerprints. Syst Appl Microbiol, 2002; 25(2):275–83. CrossRef

Flórez LV, Biedermann PHW, Engl T, Kaltenpoth M. Defensive symbioses of animals with prokaryotic and eukaryotic microorganisms. Nat Prod Rep, 2015; 32:904–36 CrossRef

Gandelman JFS, deMarval MG, Oeleman WMR, Laport MS. Biotechnological potential of sponge-associated bacteria. Curr Pharm Biotechnol, 2014; 15(2):143–55. CrossRef

Gao X, Haynes SW, Ames BD, Wang P, Vien LP, Walsh CT, Tang Y. Cyclization of fungal nonribosomal peptides by a terminal condensation-like domain. Nat Chem Biol, 2012; 8(10):823–30. CrossRef

Gonzalez O, Ortiz-Carstro R, Diaz-Perez C, Diaz-Perez AL, Magana-Duenas V, Lopez-Buclo J, Campos-Garcia J. Non-ribosomal peptide synthases from Pseudomonas aeruginosa play a role in cyclopeptide biosynthesis, quorum-sensing regulation, and root development in a plant host. Microb Ecol, 2016; 73(3):616–29. CrossRef

Han M, Lian-zhi M, Xu-ping L, Jing Z, Xiao-fei L, Hui. ERIC-PCR genotyping of Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates from hemorrhagic pneumonia cases in mink. Vet Rec Open, 2014; 1(1):1–3. CrossRef

Hanif N, Murni A, Tanaka C, Tanaka J. Marine natural products from Indonesian waters. Mar Drugs, 2019; 17(6):1–69. CrossRef

Isnansetyo A, Kamei Y. Bioactive substances produced by marine isolates of Pseudomonas. J Ind Microbiol Biotechnol, 2009; 36(10):1239–48. CrossRef

Johnson JS, Spakowicz DJ, Hong BY, Petersen LM, Demkowicz P, Chen L, Leopold SR, Hanson BM, Agresta HO, Gerstein M, Sodergren E. Evaluation of 16S rRNA gene sequencing for species and strain-level microbiome analysis. Nat Commun, 2019; 5029(10):1–11. CrossRef

Lalitha P, Veena V, Vidhyapriya P, Lakshmi P, Krishna R, Sakthivel N. Anticancer potential of pyrrole (1, 2, a) pyrazine 1, 4, dione, hexahydro 3-(2-methyl propyl) (PPDHMP) extracted from a new marine bacterium, Staphylococcus sp. strain MB30. Aptoptosis, 2016; 21(5):566–77. CrossRef

Li D, Liu J, Wang X, Kong D, Du W, Li H, Hse CY, Shupe T, Zhou D, Zhao K. Biological potential and mechanism of prodigiosin from Serratia marcescens subsp. Lawsoniana in human choriocarcinoma and prostate cancer cell lines. Int J Mol Sci, 2018; 19(11):1–21. CrossRef

Marchesi JR, Sato T, Weightman AJ, Martin AT, Fry JC, Hiom SJ, Dymock D, Wade WG. Design and evaluation of useful bacterium specific PCR primers that amplify genes coding for bacterial 16S rRNA. Appl Environ Microbiol, 1998; 64(2):795–9. CrossRef

Martínez?Núñez MA, López VELY. Nonribosomal peptides synthetases and their applications in industry. Sust Chem Proc, 2016; 4(13):1–8. CrossRef

Mehbub MF, Lei J, Franco C, Zhang W. Marine sponge derived natural products between 2001-2010: trend and opportunities for discovery of bioactives. Mar Drugs, 2014; 12(8):4539–77. CrossRef

Meyer BN, Ferrigini RN, Jacobsen LB, Nicholas DE, Mc Laughlin JL. Brine shrimp: a convenient general bioassay for active plant constituents. Planta Med, 1982; 45(5):31–5. CrossRef

Miller BR, Gulick AM. Structural biology of nonribosomal peptide synthetases. Methods Mol Biol, 2016; 1401:3–29. CrossRef

Moneam NMAE, Al-Assar SA, Sheradah MA, Nabil-Adam, A. Isolation, identification and molecular screening of Pseudomonas sp. metabolic pathways NRPs and PKS associated with the Red Sea Sponge, Hyrtios aff. Erectus, Egypt. J Pure Appl Microbiol, 2017; 11(3):1299–311. CrossRef

Offret C, Desriac F, Chevalier PL, Mounier J, Jégou C, Fleury Y. Spotlight on antimicrobial metabolites from the marine bacteria Pseudoalteromonas: chemodiversity and ecological significance. Mar Drugs, 2016; 14(7):1–26. CrossRef

Orishadipe AT, Ibekwe NN, Adesomoju AA, Okogun JI. Chemical composition and antimicrobial activity of the seed oil of Entandrophragma angolense (Welw) C.DC. African J Pure Appl Chem, 2012; 6(13):184–7.

Prastya ME, Astuti RI, Batubara I, Takagi H, Wahyudi AT. Chemical screening identifies an extract from marine Pseudomonas sp.-PTR-08 as an anti-aging agent that promotes fission yeast longevity by modulating the Pap1–ctt1+ pathway and the cell cycle. Mol Biol Rep, 2020; 47:33–43. CrossRef

Priyanto JA, Astuti RI, Nomura J, Wahyudi AT. Bioactive compounds from sponge-associated bacteria: anticancer activity and NRPS-PKS gene expression in different carbon sources. Am J Biochem Biotechnol, 2017; 13(4):148–56. CrossRef

Rajivgandhi GN, Ramachandran G, Kanisha CC, Li JL, Yin L, Manoharan N, Alharbi NS, Kadaikunnan S, Khaled JM, Li WJ. Anti-biofilm compound of 1, 4-diaza-2, 5-dioxo-3-isobutyl bicyclo[4.3.0]nonane from marine Nocardiopsis sp. DMS 2 (MH900226) against biofilm forming K. pneumoniae. J King Saud Univ Sci, 2020; 32(8):3495–502. CrossRef

Ravi L, Krishnan K. Cytotoxic potential of N-hexadecanoic acid extracted from Kigelia pinnata leaves. Asian J Cell Biol, 2017; 12:20–7. CrossRef

Sato M, Nakazawa T, Tsunematsu Y, Hotta K, Watanabe K. Echinomycin biosynthesis. Curr Opin Chem Biol, 2013; 17(4):537–45. CrossRef

Schirmer A, Gadkari R, Reeves CD, Ibrahim F, DeLong EF, Hutchinson CR. Metagenomic analysis reveals diverse polyketide synthase gene cluster in microorganisms associated with the marine sponge Discodermia dissoluta. Appl Environ Microbiol, 2005; 71(8):4840–9. CrossRef

Su P, Wang DX, Ding SX, Zhao J. Isolation and diversity of natural product biosynthetic genes of cultivable bacteria associated with marine sponge Mycale sp. from the coast of Fujian, China. Can J Microbiol, 2014; 60(4):217–25. CrossRef

Tambadou F, Lanneluc I, Sable S, Klein L, Doghri I, Sopena V, Didelot S, Barthelemi C, Thiery V, Chevrot R. Novel nonribosomal peptide synthetase (NRPS) genes sequenced from intertidal mudflat bacteria. FEMS Microbiol Lett, 2014; 357(2):123–30. CrossRef

Tokasaya P. Sponge-associated bacteria producing antimicrobial compounds and their genetic diversity analysis. Thesis, Bogor Agricultural University, Bogor, Indonesia, 2010.

Vázquez-Rivera D, González O, Guzmán-Rodríguez J, Díaz-Pérez AL, Ochoa-Zarzosa A, López-Bucio J, Meza-Carmen V, Campos-García J. Cytotoxicity of cyclodipeptides from Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1 leads to apoptosis in human cancer cell lines. BioMed Res Int, 2015; 197608:1–9. CrossRef

Versalovic J, Koeuth T, Lupski JR. Distribution of repetitive DNA sequences in eubacteria and application to fingerprinting of bacterial genomes. Nuc Ac Res, 1991; 19(24):6823–31. CrossRef

Vijayalakshmi K, Jagathy K. Production of prodigiosin from Serratia marcescens and its antioxidant and anticancer potential. Int J Adv Res Biol Sci, 2016; 3(3):75–88.

Wahyudi AT, Priyanto JA, Maharsiwi W, Astuti RI. Screening and characterization of sponge-associated bacteria producing bioactive compounds anti-Vibrio sp. Am J Bichem Biotechnol, 2018; 14(3):221–9. CrossRef

Yoghiapiscessa D, Batubara I, Wahyudi AT. Antimicrobial and antioxidant activities of bacterial extracts from marine bacteria associated with sponge Stylotella sp. Am J Biochem Biotechnol, 2016; 12(1):36–46. CrossRef

Ziemert N, Lechner A, Wietz M, Millán-Aguiñaga N, Chavarria KL, Jensen PR. Diversity and evolution of secondary metabolism in the marine actinomycete genus Salinispora. PNAS, 2014; 111(12):E1130–9. CrossRef