INTRODUCTION

Drugs are used to prevent, diagnose, and/or treat diseases, but their usage is also potentially harmful. In the US alone, medication errors account for the third leading cause of death (Makary and Daniel, 2016). The importance of preventing medication errors drove developed countries to establish effective clinical pharmacy services (Rotta et al., 2015), but the same cannot be said for nations such as China (Yao et al., 2017) and Vietnam (Vo et al., 2012), where the overall coverage of clinical pharmacy services is low.

Clinical pharmacy first developed in Vietnam in the 1990s, but the most recent development in the sector is the Ministry of Health’s release of the Guidelines on Clinical Pharmacy Practice in Hospitals in 2012 to encourage and develop clinical pharmacy activities (Vietnamese Ministry of Health, 2012). Among the key undertakings in this regard is the review of prescriptions and patient records by pharmacists (Vietnamese Ministry of Health, 2012). Medication review (MR) is a structured, critical examination of drugs prescribed to a patient, with the objective of optimizing health (Vo et al., 2012) through pharmacist interventions (PIs) intended to prevent drug-related problems (DRPs). A DRP is “an event or circumstances involving drug treatment that actually or potentially interferes with the patient’s desired health outcome” (Hepler and Strand, 1990), and PIs are “any action by a pharmacist that directly resulted in a change to patient management or therapy” (The Society of Hospital Pharmacists of Australia Committee of Specialty Practice in Clinical Pharmacy, 2005).

The lack of validated MR tools leads to poor-quality evaluations of issues related to medication, difficulties in detecting DRPs, and inadequate communication among pharmacists, doctors, and nurses. Our survey of 48 Vietnamese hospitals (Hoang, 2016) revealed that only 18 of the institutions have formalized forms that support MR. The rest have unsatisfactory documents that abound with insufficient, unstructured, and time-consuming data entries. In consideration of these issues, the present study was conducted to develop and validate a structured, comprehensive, and practicable instrument that facilitates and supports periodic MRs by clinical pharmacists.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Developing the tool

The tool, called Vi-Med®, was developed in four steps. First, information on previously developed MR tools was searched in PubMed and Google using the keywords “MR form,” “MR tools,” and “MR guide.” We found and used tools that were developed in the UK (Clinical Commissioning Group – NHS, 2014; Taskforce on Medicines Partnership, The National Collaborative Medicines Management Services Programme, 2002; The Northern Health and Social Services Board, 2003), the US (McCurdy, 1993), France (Allenet et al., 2006), Australia (National Prescribing Service, 2000), and Vietnam (Nguyen, 2015; Vietnamese Ministry of Health, 2012) to acquire insights into the development of our tool. Second, MR forms used in Vietnamese hospitals were collected through an online survey administered over a professional website. We received 18 different forms from 18 hospitals. Third, existing tools were adapted, and experts’ experiences were referred to in the development of Vi-Med®. We designed the tool in such a way that not only covers a coding system that satisfies the main requirements defined by van Mil et al. (2004) (i.e., a coding form and definitions/descriptions of DRPs and PIs) but also supports the collection and analysis of patient data during the MR process. Finally, Vi-Med® was piloted in two hospitals for modification by two clinical pharmacists, who used the tool in clinical practice and provided feedback. Vi-Med® was modified several times until a final version was established.

Validating Vi-Med®

A panel of six pharmacists who practice clinical pharmacy on a daily basis were selected from six national hospitals in Vietnam. The selection criteria were (1) having a postgraduate diploma in pharmacology – clinical pharmacy or pharmacy management, (2) currently practicing clinical pharmacy in a hospital, and (3) having at least seven years of work experience. From data on daily practice and clinical references, we randomly selected 30 PI cases, each comprising a brief description of a given medical context, all relevant information concerning a potential or identified DRP, and intervention(s) suggested by a pharmacist. The pharmacists were asked to categorize 30 PI-associated scenarios under appropriate DRPs and corresponding interventions.

Concordance among the panel members was determined using the kappa coefficient of concordance (κ) and the percentage of agreement (%) among the experts as regards the classification of DRPs and PIs. Percentage (%) and kappa (κ) were calculated for the evaluations of each expert pair, after which the mean of the results for 15 expert pair assessments was computed. The interpretation of kappa values was based on the Landis and Koch scale: κ <0 = poor agreement; 0.00–0.20 = slight agreement; 0.21–0.40 = fair agreement; 0.41–0.60 = moderate agreement; 0.61–0.80 = substantial agreement; 0.81–1.00 = almost perfect agreement (Landis and Koch, 1977; Sim and Wright, 2005).

Acceptability and ease of use

The tool’s ease of use and acceptability (whether the experts believe they would be happy using the tool in everyday practice) were rated on the basis of six clinical pharmacists and a four-point Likert scale (very good = 3, quite good = 1, not enough = −1, not at all = −3). The clarity and rationality of structure and satisfaction with content were assessed, and overall opinions about suitability, usefulness, and willingness to use the tool were determined.

Ethical considerations

The study assessed a retrospective database of PIs and did not change the healthcare processes of patients. Ethical approval was not necessary.

Data analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using the Stata statistical package (version 9.1) (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Developing Vi-Med®

Vi-Med® comes with three forms (Appendix 1):

- Form M1: This form, which consists of two pages, is intended for the collection of important patient data by pharmacists. The information resources accessed in this regard are prescriptions, medical records, and discussions with physicians, nurses, or patients.

- Form M2: This form is for the review of drug use and provides a space for pharmacists to write down critical perspectives regarding drugs prescribed to patients, detected DRPs, and proposed PIs.

- Form M3: This form, also comprising two pages, is meant for PI documentation. It contains essential information on a PI that needs to be recorded, such as patient information, short descriptions and classifications of DRPs and PIs, methods by which a pharmacist and a physician communicate with respect to PI-related recommendations, and a physician’s acceptance of PIs. Only one DRP and one PI are recorded in this form. At the back of the form is an appendix that lists eight-core DRPs with definitions, descriptions, or examples, which are meant to help pharmacists recall issues that are important to MRs.

In Vietnam, clinical pharmacy activities are implemented in various ways (Vo et al., 2012). Thus, the lack of standardization and supporting tools for daily practice is one of the principal barriers to the improvement of clinical pharmacy practice in the country (Hoang, 2016). Some documentations that encourage pharmacovigilance are used, such as those for reporting adverse drug reactions, drug quality issues, and medication errors (Vietnamese Ministry of Health, 2015). Additionally, Vietnam’s Ministry of Health issued the 2012 Guidelines on Clinical Pharmacy Practice in Hospitals, which define requirements for clinical pharmacists, human resources and facilities, general and patient-centered duties/tasks of professionals, and responsibilities of hospitals and pharmacy departments. The guidelines point out 15 primary DRPs and provide two forms for documenting PIs (one for incorporation into patient medical records and one for storage in pharmacy departments) (Vietnamese Ministry of Health, 2012). However, these DRP classifications are of poor quality. The existence of 15 types of issues may cause difficulties in categorization as a given DRP may be confused with PIs (e.g., “answering the question of a healthcare provider” is stated both as a DRP and a PI.), and some DRPs overlap (e.g., “inappropriate indication” and “contraindication”). Furthermore, the classification of PIs includes both suggestions on changes in drug use and “general concrete activities,” such as the “organization of multidisciplinary committees,” “counseling for patients,” “answering the questions of a healthcare provider,” and “re-checking patient medical records/preparing counseling at discharge.”

Some tools that support MR for clinical practice have been developed in Vietnam, as evidenced by our collection of 18 such forms from 18 Vietnamese hospitals (Hoang, 2016). The problem is that these documentations are incomplete. Some focus on patient information collection and are designed to identify administrative issues related to drug use (e.g., physician signature, availability of a committee’s opinion on the use of a specific antibiotic), but these do not reflect the exercise of clinical critical thinking. Others document only the recommendations of pharmacists. No tool has been rigorously assessed and tested in the country.

Vi-Med® presents advantages over other tools reviewed in previous studies. To begin with, it is the first in Vietnam to support the entire MR process, from data collection and analysis to documentation on the basis of Western guidelines (Clinical Commissioning Group – NHS, 2014; The Northern Health and Social Services Board, 2003). Because it is comprehensive, the inputting of large amounts of data and the review process are highly structured, thereby ensuring that both are cost-effective and practicable (Allenet et al., 2006; The Northern Health and Social Services Board, 2003). In particular, the standard forms that accompany Vi-Med® are easy to use by pharmacy students or new clinical pharmacists in their implementation of MR in daily practice. The forms are also convenient for documentation, quality accreditation, and training.

Second, we developed our own simple but exhaustive system of codifying DRPs and PIs to best meet the requirements of the Vietnamese setting. Our review of the literature yielded numerous tools for the classification and documentation of DRPs and PIs on the grounds of implicit (Pharmaceutical Care Network Europe Foundation, 2010; Schaefer, 2002; Vo et al., 2018) or explicit (Levy et al., 2010; Mast et al., 2015) criteria. Our approach to creating the coding system adheres to the fundamental requirements defined by van Mil et al. (2004); that is, a tool should comprise a coding form, descriptions of PIs, and definitions of DRPs. We did not establish an excessive number of categories as this would cause difficulties in recall. However, to ensure that no problems are missed, each type of DRP in our tool encompasses subtypes. For example, the DRP “adverse drug reaction” consists of subtypes “adverse drug effects,” “drug allergies,” and “drug intoxication.” In our previous work (Vo et al., 2018), a summary of the main validated coding system found in our literature review indicated that the underlying coding system had four to 10 DRP types and 11 to 48 subgroups as well as four to 11 PI types and 15 to 56 subgroups. By contrast, Vi-Med® consists of eight DRPs and 23 subgroups as well as seven PIs—a composition similar to a tool developed for the French context (Allenet et al., 2006).

Third, the DRPs encompassed in Vi-Med® center on concrete drug therapy issues, and the PIs are related only to concrete suggestions regarding modifications to drug therapy. We excluded “patient non-compliance” as a type of DRP because this issue is a complicated problem that is associated with multiple factors; it, therefore, requires more dedicated intervention from healthcare providers and patient participation. “Counseling for patients” and “answering the question of a healthcare provider” were excluded as PIs because these indicators can be quantified easily as process-related indicators but do not demonstrate whether these interventions change drug use by patients. In validating Vi-Med®, an expert recommended that we add some types of DRPs or PIs related to nursing practice, such as reconstitution, dilution, and length of administration. These problems, however, are classified under one of the eight DRPs called “suboptimal administration mode.”

Validating Vi–Med®

Reliability criteria

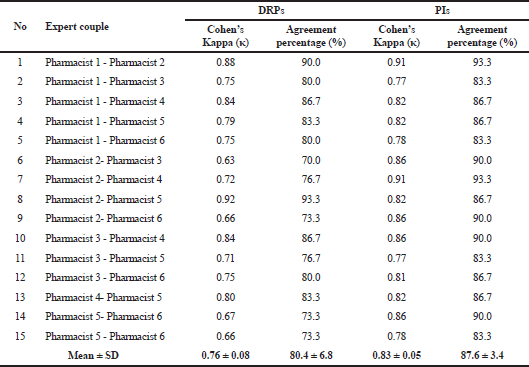

Table 1 shows the level of agreement among the experts. The kappa coefficient for the coding of DRP types was substantial (κ = 0.76; 80.4% agreement), and that for the coding of PI types was almost perfect (κ = 0.83; 87.6% agreement).

A summary of the main validated coding systems found in the literature search was provided by Vo et al. (2018). Previous studies employed a range of 20 to 106 cases rated by two to 92 coders, and in our research, we used 30 cases coded by six clinical pharmacists. The substantial agreement among the panel members in terms of DRP classification was better than that obtained by Hohmann et al. (2012) (κ = 0.58–0.68) and similar to and worse than the levels derived by Allenet et al. (2006) (κ = 0.73–0.82) and Fernandez-Llamazares et al. (2012) (κ = 0.87; 95% agreement). The almost perfect agreement as regards intervention classification was slightly lower than that observed for a French hospital tool (κ = 0.87–0.91) (Allenet et al., 2006). Note, however, that comparing the κ statistics of different coding systems is difficult because such component depends on the cases themselves, the number and profile of encoders, and the characteristics of the tool being tested (number of types, subtypes) (Landis and Koch, 1977; Sim and Wright, 2005).

Acceptability and ease of use

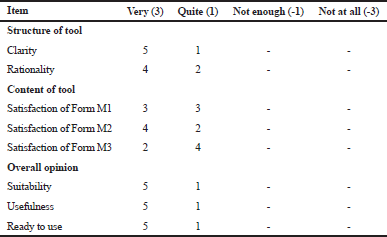

Table 2 presents the opinions of the experts regarding the acceptability and ease of use of Vi-Med®. Most of them were satisfied with the instrument’s user-friendliness as a tool for daily routines and expressed a readiness to adopt it in their everyday practice. Almost all of them were also satisfied with the tool’s structure and content. Overall, the panel judged the tool as highly suitable and useful as well as definitely suited for use in everyday practice.

| Table 1. Results on the reliability of Vi-Med®. [Click here to view] |

| Table 2. Perceptions of raters about Vi-Med®. [Click here to view] |

Limitations

The limitations of the research are worth noting. Vi-Med® is accompanied with paper-based forms that provide a fixed amount of free space to be filled in, but complicated clinical cases require more space for notes or explanations. To solve this problem, we intend to develop electronic forms that can be automatically printed. Form 2 could be designed in more detail to support clinical critical thinking by pharmacists during MRs. With regard to the validation of the tool, we implemented the test on the basis of only a small sample of scenarios and involved only a few pharmacists. Another limitation is that no test was conducted to verify intra-rater reliability (degree of agreement among repeated coding rounds).