INTRODUCTION

Consumers of herbal and dietary supplements (HDS) generally assume that these products are “natural” and therefore are safe (Boullata and Nace, 2000). However, HDS may produce untoward effects similar to conventional medicines due to the chemical moieties they contained. In fact, previous studies have reported mortality (Maddukuri and Bonkovsky, 2014) and hospitalizations resulting from HDS use (Geller et al., 2015). Other related studies have also revealed that HDS are commonly used by older people (Reinhard et al., 2014; Schnabel et al., 2014) and pregnant women (Strouss et al., 2014), who are prone to an increased risk of HDS adverse effects due to the physiological and pharmacokinetic changes in their body. In addition, HDS may interact with modern medicines, and therefore, can either enhance toxicity or render conventional medicines to become less effective. In a study conducted in Hungary, out of 1,563 prescribed medicines and 490 types of HDS used by 197 patients, the researchers found 365 and 718 HDS-drug interactions based on the Lexi-Interact and Medscape databases, respectively (Végh et al., 2014).

In a Malaysian study by Wong et al. (2018), almost all community pharmacists (CPs) surveyed, stocked HDS. Since HDS are widely available in community pharmacies, CPs should have the responsibility to ensure that HDS are used safely and appropriately. This can be achieved through a thorough assessment of customers’ HDS use by CPs (Gabay et al., 2017). In this regard, CPs should determine the appropriateness of HDS use by using all information obtained from patients or consumers and ensure the safety of users by identifying problems associated with HDS use such as HDS-drug interactions and adverse effects.

In the recently published White Paper on Natural Products by the American College of Clinical Pharmacy in 2016, pharmacists are recommended to include HDS in their patient assessment (Gabay et al., 2017). There is limited information about the extent to which pharmacists assess HDS use in the literature. However, existing information showed that this activity was not routinely performed. In a study in Australia, Braun and Cohen (2007) found that only 24% of the pharmacists surveyed, always checked for adverse effects and HDS-drug interactions. In a similar study in Iran, the authors found that the rate to which CPs checked HDS-drug interactions was moderate (Mehralian et al., 2014).

Previous studies have revealed that several factors such as practice settings (Abahussain et al., 2007; Dolder et al., 2003), age (Braun and Cohen, 2007; Chen et al., 2016), personal use of HDS (Dolder et al., 2003), and qualifications (Chen et al., 2016) were associated with higher involvement of pharmacists in patient-care activities related to HDS. However, such contextual factors may not be suitable to be targeted in promoting CPs to become more proactive in assessing HDS use. Social pharmacy researchers often study pharmacists’ behavioral intention to engage in a certain activity as it is the most proximate predictor of behavior (Ajzen, 1991). This was shown in a study in the United States, where pharmacists’ behavioral intention was a significant predictor of the actual implementation of general pharmaceutical care (Odedina et al., 1997). Therefore, to promote pharmacists’ behavior performance, pharmacists’ behavioral intention should be enhanced. The formation of pharmacists’ behavioral intentions, however, can be influenced by several psychosocial factors such as attitude, subjective norm, perceived behavioral control, and moral norm (Farris and Schopflocher, 1999; Gavaza et al., 2014; Herbert et al., 2006; Odedina et al., 1997; Puspitasari et al., 2016), warranting the investigation of these contributing factors.

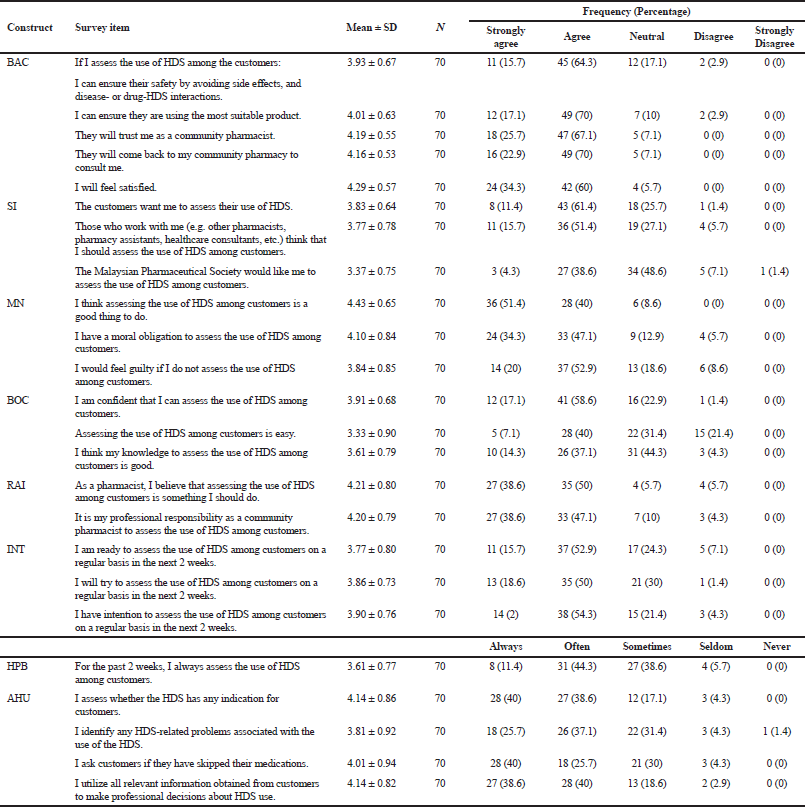

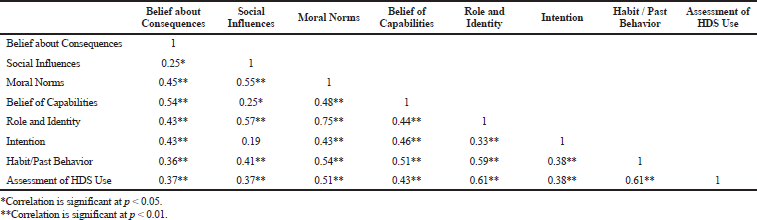

In a systematic review that compiled theory-based studies that predicted intention and behavior of healthcare professionals in various clinical-related activities (Godin et al., 2008), the authors illustrated several variables that are important in the prediction of intention and behavior of healthcare professionals. The authors proposed that beliefs about consequences (BAC), social influences (SI), moral norms (MN), role and identity (RAI), belief of capabilities (BOC), and habit/past behavior (HPB) have a positive relationship with intention (INT). Additionally, INT, HPB, and BOC are expected to have a direct link with behavior [assessment of HDS use (AHU)]. Therefore, the main objective of this present study was to determine BAC, SI, MN, RAI, BOC, HPB, INT, and AHU among a sample of CPs in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. The study also aims to explore the inter-relationship of the variables proposed by Godin et al. (2008) in the context of HDS use assessment by CPs.

METHODS

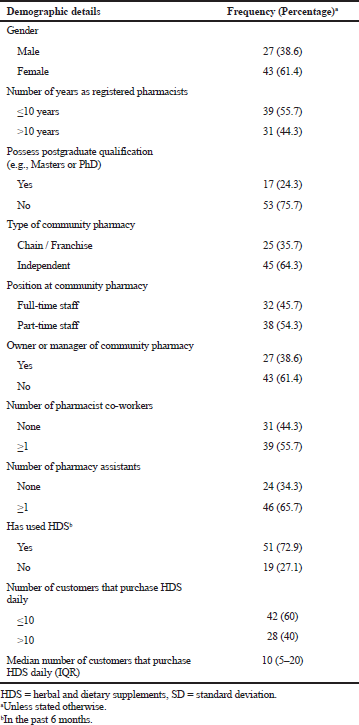

This study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Universiti Teknologi MARA (UiTM) (REC/464/18). The study respondents consisted of CPs employed as full- or part-time pharmacists in community pharmacies in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. Only CPs who had direct contact with customers or patients at their workplaces were included in the study. Data were collected using postal survey. A cover letter along with the questionnaire and stamped envelope were mailed to all community pharmacies in Kuala Lumpur in the first week of April 2018. The sampling frame was a list of community pharmacy addresses in Kuala Lumpur, obtained from the official website of Pharmaceutical Services Divisions of the Ministry of Health, Malaysia (Pharmaceutical Services Division MOH, 2018). A reminder postcard was sent to all addresses approximately a week after the first mailing to promote CPs to respond to the survey. Total anonymity and confidentiality were maintained throughout the study which was informed to all CPs. Data collection was finalized in the third week of May 2018. In this study, HDS refer to products containing plant-derived materials or dietary ingredients, e.g., vitamins, minerals, amino acids, and substances such as enzymes, organ tissues, glands, metabolites, extracts, and concentrates in the form of pills, capsules, tablets, powder, or liquids that are taken to treat and/or prevent diseases or maintain health (The World Health Organization, 2000; U.S. Food & Drug Administration, 2015).

Survey instrument

The survey instrument was developed based on the proposed framework of constructs by Godin et al. (2008) that may influence healthcare professionals’ intention and behavior in various clinical-related activities including the provision of care to patients. Generation of items was done by adapting similar items from previous studies (Gavaza et al., 2011; 2014; Herbert et al., 2006; Puspitasari et al., 2016; Wahab et al., 2019). The questionnaire contains eight scales representing BAC, SI, MN, BOC, RAI, INT, HPB, and AHU. The definition and number of items for each construct are outlined in Table 1. The domains HPB and AHU used a 5-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (never) to 5 (always), whereas the other six domains (BAC, SI, MN, BOC, RAI, and INT) used a 5-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). The questionnaire included a socio-demographic section to collect demographic data such as gender, position at work, and history of HDS use that have been identified as factors that may influence CPs to engage in pharmacist-related activities related to HDS (Barnes and Abbot, 2007; Dolder et al., 2003; Welna and Hadsall, 2003). The survey instrument was reviewed by five pharmacy practice researchers to assess the relevance of each survey item. Additionally, the questionnaire was administered to a convenient sample of CPs to obtain feedback about the clarity and comprehensibility of survey items. Minor changes were made to the items by rephrasing them based on the feedback obtained from the experts and CPs.

Data analysis

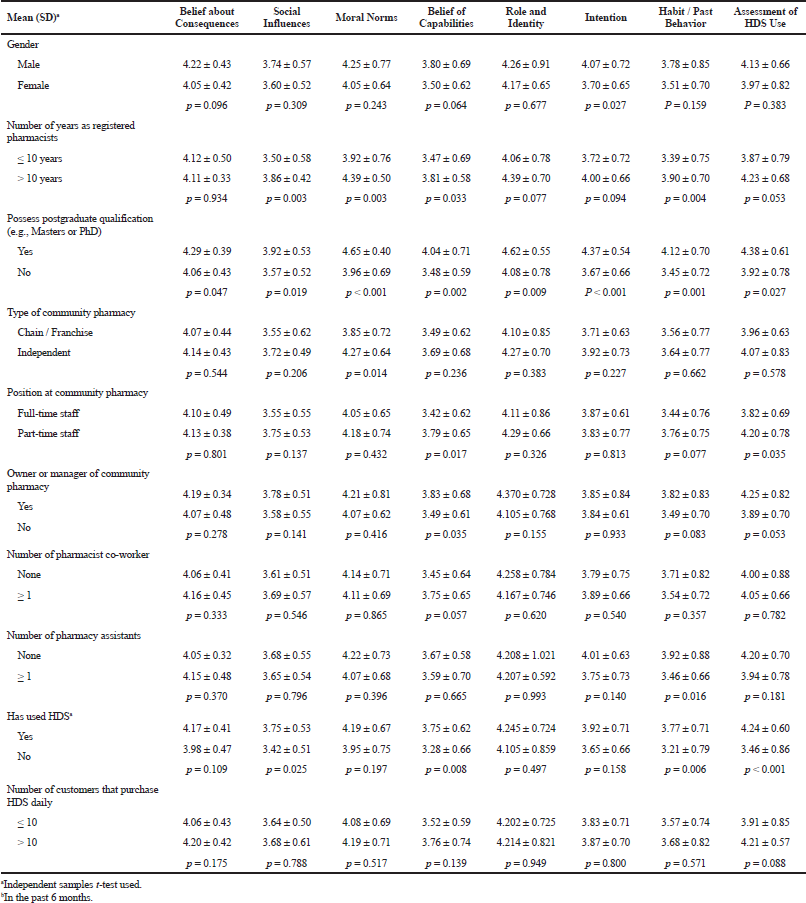

The frequencies, means, and standard deviations were computed for all item scores. The internal consistency reliability of scales comprising of at least three items (BAC, SI, MN, BOC, INT, and AHU) were assessed using Cronbach’s α. One construct has only two items. Therefore, the Spearman correlation (rho) was used to measure the correlation of the two items. All the item scores were averaged to obtain the mean score for each scale. The independent samples t-test was carried out on dichotomous socio-demographic variables to find significant differences in the mean scores of the scales. The Pearson correlation test (r) was performed to assess the correlation among constructs. The interpretation of the correlation coefficients followed the convention by Guilford as the following: ≤ 0.19 = slight or almost no relationship; 0.20–0.39 = low correlation or definite but small relationship; 0.40–0.69 = moderate correlation or substantial relationship; 0.70–0.89 = high correlation or strong relationship; and 0.90–1.00 = very high correlation or very dependable relationship (Durrheim and Tredoux, 2004). Additionally, a correlation coefficient of ≥ 0.30 implies a practically significant relationship (Steyn, 2002). All data analysis were done using SPSS version 23.

.png) | Table 1. Definition, number of items, reliability and descriptive statistics for the study scales.

[Click here to view] |

DISCUSSION

The present study revealed that CPs generally do not routinely assess customers’ HDS use.The CPs were also noted to be less proactive in identifying HDS-related problems. This should be a cause for concern since HDS can produce untoward effects (Geller et al., 2015), interact with conventional medicines (Végh et al., 2014), and may be used without clear indications (Wahab et al., 2017). Previous studies conducted in Australia and Iran also showed similar findings where pharmacists did not always check for adverse effects and HDS-drug interactions (Braun and Cohen, 2007; Mehralian et al., 2014). In another study in Iran, almost 83% of CPs did not identify any interaction when a simulated patient requested for a vitamin A supplement together with the mentioning of regular isotretinoin use (Dabaghzadeh and Hajjari, 2018). Our results also showed that CPs had moderately positive INT to assess HDS use among customers. As hypothesized, CPs’ INT to assess HDS use correlated positively and significantly with the performance of the activity. In this present study, BAC, MN, RAI, BOC, and HPB correlated positively and significantly with INT. Among these constructs, BOC, BAC, and MN had the strongest correlation with INT. Therefore, in efforts to enhance the INT of CPs to assess HDS use, enhancing BOC, BAC, and MN can be prioritized.

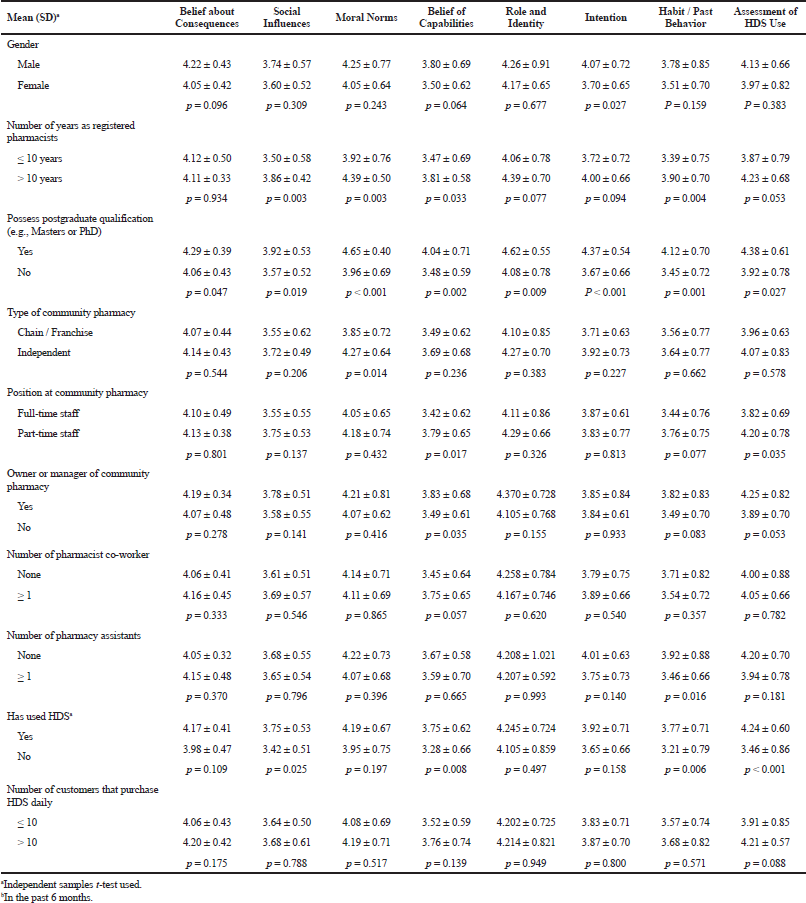

| Table 4. Comparison of scales’ mean based on community pharmacists’ socio-demographic characteristics.

[Click here to view] |

BOC can be enhanced by providing CPs with training and continuous education in pharmaceutical care, especially related to HDS. This is important since previous studies have shown that knowledge about HDS is inadequately covered in the undergraduate pharmacy curricula (Wahab et al., 2014; 2016). Pharmacists in general, however, welcome more training in the area (Ung et al., 2017). In a Malaysian study, almost all of the survey respondents were interested in having additional training in HDS (Wong et al., 2018). Other studies conducted revealed that pharmacists who had training in HDS were more likely to inquire patients about HDS use (Barnes and Abbot, 2007; Brown et al., 2005; Dolder et al., 2003), or record HDS use (Cockayne et al., 2005; Dolder et al., 2003), than those without such training. Furthermore, a lack of training related to HDS had been identified as a barrier to provide care for HDS users (Al-Arifi, 2013; Semple et al., 2006). This present study, however, did not capture whether CPs have had previous training in HDS. Nevertheless, our results showed that CPs with a postgraduate qualification had higher BOC level than those with only an undergraduate education, suggesting that additional training in pharmacy may enhance CPs to become more confident in assessing HDS use.

Positive BAC can be achieved by highlighting the positive consequences of assessing HDS use to CPs. In this present study, CPs were found to recognize the benefits of assessing HDS use by agreeing that the activities may result in a safer and more appropriate use of HDS, enhanced trustworthiness, increased customer loyalty, and can result in self-satisfaction. Our findings are consistent with previous studies which showed that pharmacists generally believed that their involvement in caring for HDS users is beneficial (Koh et al., 2003; Kwan et al., 2008; Song et al., 2017; Wahab et al., 2019). Additionally, the results showed that CPs who believed that they were morally obligated to assess HDS use were more likely to have the INT to perform the activity. In a previous qualitative study, moral obligation has been perceived as one of the facilitators for pharmacists to provide consultations on natural health products (Olatunde et al., 2010). Hence, pharmacy educators, employers, and professional pharmacy bodies may campaign that assessing HDS use is beneficial for the community pharmacist profession, and highlight that moral obligation of CPs is not only limited to assessing drug use but should also be extended to assessing HDS use.

The present study also showed that SI was not significantly correlated with CPs’ INT to assess HDS use. The CPs in the present study had a moderate agreement with all three SI statements. CPs had the lowest agreement with the statement that the local pharmacists' society would like them to assess their customers’ HDS use. This finding implies that there is still limited attention by the national pharmacy association to encourage CPs to care for HDS users. At present, there is also a limited statement from Malaysian pharmacy organizations or societies that urge CPs to integrate HDS in professional pharmacy practice. For example, the Malaysian “Community Pharmacy Benchmarking Guidelines 2015,” only briefly mentioned that CPs should advise on HDS use (Pharmaceutical Services Division MOH, 2015). Other professional pharmacist’s activities such as assessing and documenting HDS use and assisting customers in making an informed decision about using HDS are not included in the guideline. The CPs, however, had a more positive agreement that the customers want them to assess their HDS use. This is favorable since past studies have shown that pharmacists perceive customers who actively seek their consultations by initiating conversation or asking questions about HDS as a facilitator for them to provide care (Al-Arifi, 2013; Barnes and Abbot, 2007; Bushett et al., 2011; Ogbogu and Necyk, 2016). This means that the more engagement the HDS users had with CPs, the more likely the CPs would provide care for them. Therefore, in efforts to promote safe and appropriate use of HDS, in addition to targeting CPs, the HDS users should also be targeted by encouraging them to consult CPs about their HDS use.

REFERENCES

Abahussain NA, Abahussain EA, Al-Oumi FM. Pharmacists' attitudes and awareness towards the use and safety of herbs in Kuwait. Pharm Pract (Granada), 2007; 5(3):125–9. CrossRef

Ajzen I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ Behav Hum Perform, 1991; 50(2):179–211. CrossRef

Al-Arifi MN. Availability and needs of herbal medicinal information resources at community pharmacy, Riyadh region, Saudi Arabia. Saudi Pharm J, 2013; 21(4): 351–60. CrossRef

Barnes J, Abbot NC. Professional practices and experiences with complementary medicines: a cross sectional study involving community pharmacists in England. Int J Pharm Pract, 2007; 15(3):167–75. CrossRef

Boullata JI, Nace AM. Safety issues with herbal medicine. Pharmacotherapy, 2000; 20(3):257–69. CrossRef

Braun LA, Cohen MM. Australian hospital pharmacists' attitudes, perceptions, knowledge and practices of CAMs. J Pharm Pract Res, 2007; 37(3):220–4. CrossRef

Brown CM, Barner JC, Shah S. Community pharmacists’ actions when patients use complementary and alternative therapies with medications. J Am Pharm Assoc (2003), 2005; 45(1):41–7. CrossRef

Bushett NJ, Dickson-Swift VA, Willis JA, Wood P. Rural Australian community pharmacists' views on complementary and alternative medicine: a pilot study. BMC Complement Altern Med, 2011; 11(1):103. CrossRef

Chen X, Ung COL, Hu H, Liu X, Zhao J, Hu Y, Li P,Yang Q. Community pharmacists’ perceptions about pharmaceutical care of traditional medicine products: a questionnaire-based cross-sectional study in Guangzhou, China. Evid Based Complement Altern Med, 2016; 2016. CrossRef

Cockayne NL, Duguid M, Shenfield GM. Health professionals rarely record history of complementary and alternative medicines. Br J Clin Pharmacol, 2005; 59(2):254–8. CrossRef

Dabaghzadeh F, Hajjari R. Practice of community pharmacists related to multivitamin supplements: a simulated patient study in Iran. Int J Clin Pharm, 2018; 40(1):190–5. CrossRef

Dolder C, Lacro J, Dolder N, Gregory P. Pharmacists' use of and attitudes and beliefs about alternative medications. Am J Health Syst Pharm, 2003; 60(13):1352. CrossRef

Durrheim K, Tredoux C. Numbers, hypotheses & conclusions: a course in statistics for the social sciences. Juta and Company Ltd, Kenwyn, South Africa, 1999.

Farris KB, Schopflocher DP. Between intention and behavior: an application of community pharmacists' assessment of pharmaceutical care. Soc Sci Med, 1999; 49(1):55–66. CrossRef

Gabay M, Smith JA, Chavez ML, Goldwire M, Walker S, Coon SA, Gosser R, Hume AL, Musselman M,Phillips J. White paper on natural products. Pharmacotherapy, 2017; 37(1):e1–15. CrossRef

Gavaza P, Brown CM, Lawson KA, Rascati KL, Wilson JP,Steinhardt M. Examination of pharmacists’ intention to report serious adverse drug events (ADEs) to the FDA using the theory of planned behavior. Res Soc Adm Pharm, 2011; 7(4):369–82. CrossRef

Gavaza P, Fleming M, Barner JC. Examination of psychosocial predictors of Virginia pharmacists' intention to utilize a prescription drug monitoring program using the theory of planned behavior. Res Soc Adm Pharm, 2014; 10(2):448–58. CrossRef

Geller AI, Shehab N, Weidle NJ, Lovegrove MC, Wolpert BJ, Timbo BB, Mozersky RP,Budnitz DS. Emergency department visits for adverse events related to dietary supplements. N Engl J Med, 2015; 373(16):1531–40. CrossRef

Godin G, Bélanger-Gravel A, Eccles M,Grimshaw J. Healthcare professionals' intentions and behaviours: A systematic review of studies based on social cognitive theories. Implement Sci, 2008; 3(1):36. CrossRef

Herbert KE, Urmie JM, Newland BA, Farris KB. Prediction of pharmacist intention to provide Medicare medication therapy management services using the theory of planned behavior. Res Soc Adm Pharm, 2006; 2(3):299–314. CrossRef

Koh H-L, Teo H-H, Ng H-L. Pharmacists' patterns of use, knowledge, and attitudes toward complementary and alternative medicine. J Altern Complement Med, 2003; 9(1):51–63. CrossRef

Kwan D, Boon HS, Hirschkorn K, Welsh S, Jurgens T, Eccott L, Heschuk S, Griener GG, Cohen-Kohler JC. Exploring consumer and pharmacist views on the professional role of the pharmacist with respect to natural health products: a study of focus groups. BMC Complement Altern Med, 2008; 8(1):40. CrossRef

Maddukuri VC, Bonkovsky HL. Herbal and dietary supplement hepatotoxicity. Clin Liver Dis, 2014; 4(1):1–3. CrossRef

Mehralian G, Yousefi N, Hashemian F, Maleksabet H. Knowledge, attitude and practice of pharmacists regarding dietary supplements: a community pharmacy-based survey in Tehran. Iran J Pharm Res, 2014; 13(4):1457–65.

Odedina FT, Hepler CD, Segal R, Miller D. The pharmacists' implementation of pharmaceutical care (PIPC) model. Pharm Res, 1997; 14(2):135–44. CrossRef

Ogbogu U, Necyk C. Community pharmacists’ views and practices regarding natural health products sold in community pharmacies. PloS one, 2016; 11(9):e0163450. CrossRef

Olatunde S, Boon H, Hirschkorn K, Welsh S, Bajcar J. Roles and responsibilities of pharmacists with respect to natural health products: key informant interviews. Res Soc Adm Pharm, 2010; 6(1):63–9. CrossRef

Pharmaceutical Services Division Ministry of Health Malaysia. Community pharmacy benchmarking guideline, 2015. Available via https://www.pharmacy.gov.my/v2/en/documents/community-pharmacy-benchmarking-guideline.html (Accessed July 10 2019).

Pharmaceutical Services Division Ministry of Health Malaysia. Daftar lesen, 2018. Available via https://www.pharmacy.gov.my/v2/ms/maklumat/daftar-lesen.html (Accessed April 30 2018).

Puspitasari HP, Costa DS, Aslani P, Krass I. An explanatory model of community pharmacists' support in the secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease. Res Soc Adm Pharm, 2016; 12(1):104–18. CrossRef

Reinhard MJ, Nassif TH, Bloeser K, Dursa EK, Barth SK, Benetato B, Schneiderman A. CAM utilization among OEF/OIF veterans: findings from the National Health Study for a new generation of US veterans. Med Care, 2014; 52:S45–9. CrossRef

Schnabel K, Binting S, Witt CM, Teut M. Use of complementary and alternative medicine by older adults–a cross-sectional survey. BMC Geriatrics, 2014; 14(1):1. CrossRef

Semple SJ, Hotham E, Rao D, Martin K, Smith CA, Bloustien GF. Community pharmacists in Australia: barriers to information provision on complementary and alternative medicines. Pharm World Sci, 2006; 28(6):366–73. CrossRef

Song M, Ung COL, Lee VW-y, Hu Y, Zhao J, Li P, Hu H. Community pharmacists’ perceptions about pharmaceutical service of over-the-counter traditional Chinese medicine: a survey study in Harbin of China. BMC Complement Altern Med, 2017; 17(1):9. CrossRef

Steyn H. Practically significant relationships between two variables. SA Journal of Industrial Psychology, 2002; 28(3):10–5. CrossRef

Strouss L, Mackley A, Guillen U, Paul DA, Locke R. Complementary and Alternative Medicine use in women during pregnancy: do their healthcare providers know? BMC Complement Altern Med, 2014; 14(1):1. CrossRef

Taber KS. The use of Cronbach’s alpha when developing and reporting research instruments in science education. Res Sci Educ, 2018; 48(6):1273–96. CrossRef

Ung COL, Harnett J, Hu H. Community pharmacist's responsibilities with regards to traditional medicine/complementary medicine products: a systematic literature review. Res Soc Adm Pharm, 2017; 13(4):686–716. CrossRef

U.S. Food & Drug Administration. Questions and answers on dietary supplements, 2015. Available via https://www.fda.gov/drugs/questions-answers/dietary-supplements-questions-and-answers (Accessed April 30 2019).

Végh A, Lankó E, Fittler A, Vida RG, Miseta I, Takács G, Botz L. Identification and evaluation of drug–supplement interactions in Hungarian hospital patients. Int J Clin Pharm, 2014; 36(2):451–9. CrossRef

Wahab MSA, Ali AA, Zulkifly HH, Aziz NA. The need for evidence-based complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) information in Malaysian pharmacy curricula based on pharmacy students’ attitudes and perceptions towards CAM. Curr Pharm Teach Learn, 2014; 6(1):114–21. CrossRef

Wahab MSA, Othman N, Othman NHI, Jamari AA, Ali AA. Exploring the use of and perceptions about honey as complementary and alternative medicine among the general public in the state of Selangor, Malaysia. J Appl Pharm Sci, 2017; 7(12):144–50.

Wahab MSA, Sakthong P, Winit-Watjana W. Pharmacy students’ attitudes and perceptions about complementary and alternative medicine: a systematic review. Thai J Pharm Sci, 2016; 40(2).

Wahab MSA, Sakthong P, Winit-Watjana W. Development and validation of novel scales to determine pharmacist's care for herbal and dietary supplement users. Res Soc Adm Pharm, 2019 (Article in press). CrossRef

Wahab MSA, Sakthong P, Winit-Watjana W. Qualitative exploration of pharmacist care for herbal and dietary supplement users in Thai community pharmacies. J Pharm Health Serv Res, 2019; 10(1):57–66. CrossRef

Welna EM, Hadsall RS. Pharmacists’ personal use professional practice behaviors and perceptions regarding herbal and other natural products. J Am Pharm Assoc (2003), 2003; 43(5):602–11. CrossRef

Wong PN, Braun LA, Paraidathathu T. Exploring the interface between complementary medicine and community pharmacy in Malaysia—a survey of pharmacists. Malays J Public Health Med, 2018; 18(1):130–8.

World Health Organization. General Guidelines for Methodologies on Research and Evaluation of Traditional Medicine, 2000 Available via http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/66783/1/WHO_EDM_TRM_2000.1.pdf (Accessed 10 July 2019).

.png)